Walk into any child care or preschool center and what are you going to see other than small kids, toys, blocks and books?

Well, female teachers. There’s an absolute dearth of men in the field. Like, a big-time absence.

Estimates of men in early childhood teaching jobs range from 1% to 6%, with most guesses closer to the first number.

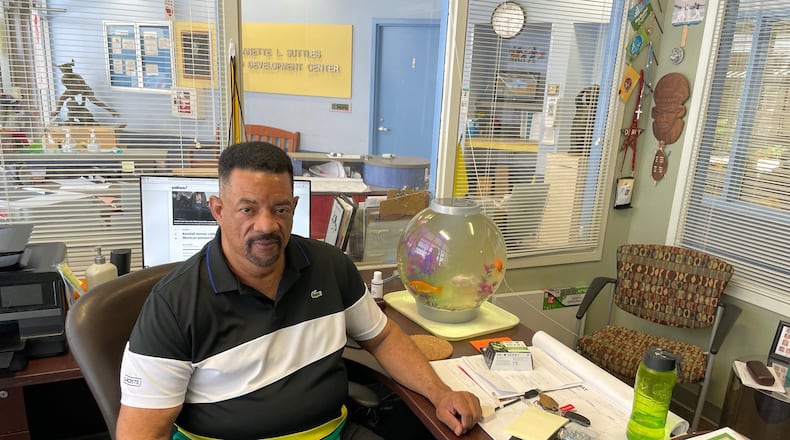

Meet Danny Darby, who’s ahead of his time, 40 years ahead. He’s a guy, he’s Black, and he’s a longtime preschool teacher, which makes him sort of a unicorn in the industry. He will retire on Tuesday as the curriculum coordinator at the Georgia State University Child Development Center after being hired there in 1981.

Former teachers at the center and his old students, some of whom are now pushing middle age, remember him as a “gentle giant” in a shirt and tie who was the guy to call in to calm an infant who would not stop wailing. Former students remember being exposed to all sorts of things at the school, such as reading, presentations about the Chinese New Year and Hanukkah, and lessons on how to resolve their problems.

They also, at a young, formative age, got something else: A relationship with a kind, professional African American man.

“That was one of the things that stood out with me,” said Reanna Bennett, who was in Darby’s class in the mid-1980s. “He’s so broad and tall. He had a large presence but he’s such a gentle spirit. We all crawled over him like monkeys.”

“Looking back, it was so creative. Georgia State is an amalgam of cultures; I feel it was ahead of its time,” said Bennett, whose mother, Ruby Hopkins, taught at the center for 35 years. Three of Bennett’s four kids also attended there. It’s almost a common theme: Toddlers taught by Darby in the 1980s and 1990s are now sending their kids to be taught by him.

Ashli A. Owen-Smith, a Georgia State professor of public health who holds a doctorate from Emory University, was potty-trained by Darby.

“Those early memories are fuzzy,” she said with a laugh. “But I remember feeling attached to him and wanting to stay. I remember how kind Danny was.”

Her son Leo now attends the school. “I wish he could get Leo potty-trained too.”

Credit: Photo courtesy of Ashli Owen-Smith

Credit: Photo courtesy of Ashli Owen-Smith

Darby has gone on to become a nationally recognized expert in incorporating play into the curriculum. One of his seminars was “STEAM (Science, Technology, Engineering, Arts, and Math) in Early Childhood: How to keep it simple and fun.” Another was creating an atmosphere that was sort of child-directed, where adults weren’t telling them everything they needed to do.

He started at a time when child care was sort of like babysitting. It has since expanded to what’s called early childhood development, although there are two schools of thought — the play-based centers or the ones with more structured programs.

“We now know how play plays such a role in development. It helps social skills, friendship skills and empathy,” Darby said during an interview in his office. “Play teaches children to cooperate. Kids don’t play outside (these days). But that’s how we picked up skills. If everything is so structured, they’re missing out on an opportunity for them to pick up skills. These are skills you learn to survive and that you need as an adult.”

Like, don’t pull your supervisor’s hair or throw blocks at other drivers.

He said some very high-end programs stick with a more structured approach because parents like more accessible benchmarks. But play-based programs are coming back in popularity. “What’s old is new,” he said.

Darby started at the center by chance. He had taught fifth grade right out of college and was ready to enroll in a master’s degree program at Georgia State when he saw a want ad for a child care center teacher. The leader at the time, Brenda Galina, was trying to professionalize the service and was increasing her teachers’ salaries to approach those of elementary school teachers. It was the only way to keep top-flight talent, she reasoned.

“They were considered more like caregivers than teachers,” said Darby, adding that the salary allowed him to have a career in the field.

With Darby being a man, Galina wondered whether he’d stay. “I can give you two years,” he assured her.

He started with toddlers and was viewed warily by some parents. “I had an assistant, so that eased parents’ minds,” he said. But not all parents. “A couple chose other options for their children,” he said.

Anthony Broughton, a professor at Claflin University in South Carolina and the school’s early childhood curriculum coordinator, said men must fight stereotypes that they aren’t nurturing and might abuse kids.

Broughton started as a kindergarten teacher out of college and stayed in the field because he wanted “children to see a Black male educator in preschool.”

“It shows them that we belong in education; that we value education. They get to know who we are,” Broughton said. “It’s a way to break stereotypes.”

Ruby Hopkins, who taught at the child center with Darby, said, “He was a good role model for students there. He wore a shirt and tie every day that he was a teacher in the classroom. Little boys would ask to wear shirts and ties in class. That’s because of his example.”

Darby said that was intentional. “Each teacher sets an example,” he said. “I just wanted to be professional.”

He noted that children’s brains are like sponges between 1 and 5 years old. His demeanor and professional manner “definitely helped them form an opinion” of him, he said. But it went much further than that. It was part of creating a caring atmosphere.

“If they’re going to be successful later on, they need to be in a loving environment early,” he said. “They need a center without a lot of stress. It’s harder to overcome children’s negative experiences from that age.”

About 20 years ago, he shifted from the classroom to coordinating the curriculum at Georgia State’s center, a place where the children of both students and faculty attend. While walking the halls at the university, he often hears “Hey, Mr. Danny” and knows it’s one of his former students. Maybe it’s a college student. Or even a professor he helped potty-train.

Darby, who lives near the old Turner Field, has no kids of his own. “I have nieces and nephews who think I’m their father,” he said.

And now, at 65 he has decided it’s time to call it a career. He’d like to see more men get into the field, to help be role models for the young sponges that are toddlers’ brains.

About the Author

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured