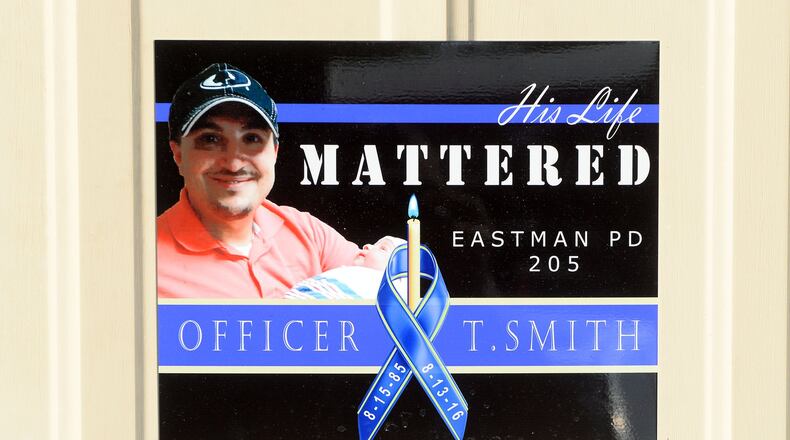

As Eastman police officer Tim Smith patrolled his small Middle Georgia town the night of Aug. 13, a critical item sat unused on the front floor of his cruiser: his city-issued bulletproof vest.

“The vest was supplied,” said Eastman Police Chief Becky Sheffield. “It was supplied and it was up to them if they wanted to wear it.”

Smith’s choice not to wear his vest proved fateful.

Around 9:30 p.m., a 911 call crackled across Smith’s radio. A man had pulled a gun on someone near an intersection on Main Street. Smith passed a suspect on foot that matched the description and flipped his blue lights on as he turned his patrol car around. Smith told the man, later identified as Royheem Delshawn Davis, to place his hands on the patrol car and said they needed to talk.

As Smith exited his vehicle, Davis pulled a gun and fired a single shot that struck Smith in the chest, according to police. Smith returned fire, but Davis escaped on foot. Smith, the father of three young children, died later that night at the hospital, just days shy of this 32nd birthday.

His death was the second time a Georgia officer was shot and killed in the line of duty this year. In each case, the officer was not wearing the bulletproof vest issued by their department. The armor — had the officers been wearing it — possibly could have saved their lives.

In February, Riverdale police Maj. Greg Barney was shot and killed during a no-knock warrant drug raid at an apartment down the street from the police department. Barney was shot in the stomach, back, leg and arm.

At the time they were shot, both Smith and Barney were operating within their respective departments’ guidelines on body armor. Those policies are now in the process of changing in both agencies.

But their deaths raise broader questions for Georgia law enforcement: How wide are the gaps in body armor use? And are department policies adequate for the more than 600 police agencies that employ thousands of officers across the state?

No one tracks how many departments supply armor to their officers and how many leave it up to the officers to decide when they put them on. In some smaller agencies, officers are expected to supply their own armor at their own expense.

In 2012, the Eastman city government, with help from local civic groups, bought body armor vests for each officer in the small department. The leadership had encouraged its 12 officers to wear the vests, but the department had no policy about when they should wear them, and little training was offered.

In large agencies, such as Atlanta’s and Cobb County’s, officers are issued body armor and are required to wear it when on patrol. In June, that armor likely saved a young Atlanta officer’s life when he was answering a call at an apartment building and a man opened the door and shot the officer at close range. The vest stunted the bullet’s impact, aimed at the officers stomach area. Stunned and shaken, he was able to return fire.

He suffered minor injuries and was released from the hospital the same night.

Policies evolving

Body armor use, even in larger departments, is still evolving. In 2014, the Georgia State Patrol moved from a policy that gave troopers the option to wear their department-issued vests to a policy that makes it mandatory. Before the change, the department estimated that 75 percent of its troopers wore vests when on patrol. Now, all troopers wear the safety vests as part of their required uniform.

Public Safety Commissioner Mark McDonough said it’s part of a broader effort to reinforce safety through annual training and regular reminders, such as signs placed in the police cruisers and inside patrol post offices. It’s a common-sense approach intended to decrease the chances of an on-duty catastrophe, he said.

“It starts with a commitment to your family,” said McDonough. “When there is (equipment) that is so prevalent and available today that can help with your own personal safety, why would you not avail yourself of it?”

He said many agencies still have policies that make wearing the vest an option. As he travels the state, he routinely sees officers in the community who aren’t wearing a body armor vest. McDonough — who holds the rank of colonel in the highway patrol — wears body armor every day as part of his uniform to set an example.

McDonough said he will sometimes greet an officer without armor and rap the plate of his own vest.

“Without even saying a word I just knock on the plate,” he said. “That little action alone drives home what I’m saying to the person: Wear your vest.”

Caught in the line of fire

Most departments with mandatory body armor requirements for patrol officers exempt command staff and officers on administrative duty. That was the case in Riverdale on Feb. 11 when the agency was backing up the Clayton County narcotics unit on a no-knock warrant.

Maj. Barney, who oversaw Riverdale’s support services division, had gone to the scene, but he wasn’t planning to be part of the operation and was within the department’s body armor guidelines because of his administrative duty, according to Riverdale Chief Todd Spivey.

“He got too close,” Spivey said. “When he went over there he didn’t know he would see something play out in front of him and he reacted to it.”

Barney chased one of the suspects who ran out a back door of the apartments. The man — Jerand Edward Ross — was about 200 feet from the apartment when he encountered Barney and opened fire. A Clayton County officer returned fire and shot Ross, who died weeks later. Barney — who was married with two teenage sons — died at the hospital the same day.

His death shook the Riverdale department and the agency increased safety training, implementing a national training program called "Below 100" intended to cut officer deaths nationwide to under 100. Currently, about 150 officers die each year in the line of duty. Roughly a third are from gunfire.

The overall number of on-duty deaths is down so far this year, but those resulting from gunfire is up 58 percent, according to the Officer Down Memorial Page website.

Spivey, who now wears his vest every day to set a tone in his agency, said the incident involving Maj. Barney and the new training has helped transform the department’s culture. After the shooting, the chief gave a verbal directive that any uniformed officer in the field, no matter the rank, must wear their vest.

The change is being incorporated into the department’s written policy. Spivey believes the step is necessary in an era where police can be targeted simply for being in uniform.

“It’s the right thing to do,” Spivey said. “It’s the right approach for this day and time.”

A ‘teddy bear’ that saved a life

Atlanta Police Officer Justin Fong-Borden knows the vest he wore probably saved his life. He returned to patrol last month.

Fong-Borden was answering a prowler call at the the Allure at Brookwood apartment complex in northeast Atlanta June 4 when he approached a door.

“The guy opened it up and started shooting,” Fong-Borden said.

Fong-Borden, whose fiance was pregnant at the time, said he’d been wearing the vest since he was in training with the force. He said it’s treated as part of the uniform and helps officers confront a wide range of situations, from a lost child, to fighting, to an alarm call, to a knife fight.

“It’s up and down all day,” Fong-Borden said. “You never know what’s going to happen. This is our comfort, our support. It’s a little teddy bear for us. I feel snug. I feel safe.”

In Eastman, a town of 5,000, each day since officer Smith’s death some new offering of sympathy arrives — cards, a blanket for Smith’s baby or pillows for his boys — sent by strangers from afar who felt the grief. One man from Utah made an oil portrait of officer Smith that the department plans to hang in the lobby.

Chief Sheffield said Smith, who liked to work the night shift, was an officer who was known to wear his vest. She will never know why he didn’t have it on the night of his death. Since then, officers in the small department are wearing their vests. Sheffield has been reviewing other departments’ body armor policies as she plans to create a new one for her officers.

The chief, a 39-year veteran who started in the department as a young secretary, said the past month has been the most trying of her law enforcement career.

“This is just something we don’t see here,” she said. “You just don’t think about it happening in a small town like this.”

She struggles to put the experience into words.

“It has been traumatic for all of us,” she said. “Hindsight, how we always look back and say we would change things. I don’t know. It has really taken a toll on all of us. I can honestly say, in all my years, I hope to God I never have to deal with anything like this again.”

About the Author

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured