Moore’s Ford lynching: years-long probe yields suspects — but no justice

The nightmares hardly come anymore. The barrage of gunshots no longer haunt his thoughts. Still, Clinton Adams has never fully escaped the horror he says he witnessed 71 years ago near a remote, wooden bridge that crossed the Apalachee River in rural Walton County.

He's been called a liar for what he says he saw near the riverbank as a young boy — a sudden burst of violence that he and a childhood friend secretly watched. It was late afternoon of July 25, 1946, when a white mob fatally shot two young black couples near the Moore's Ford bridge, 50 miles east of Atlanta.

Books about what became America’s last mass lynching have raised doubts about Adams’ story. And investigators have questioned his most explosive claim: that he witnessed a Georgia law officer actively participate in the killings.

"You can't forget something that's buried in your mind," he said recently. "I was there. I know what happened."

Adams remained silent for 45 years, but when he finally spoke out in 1991 his story helped breathe new life into the cause of identifying and holding the killers accountable. That public interest has continued more or less unabated for the past quarter century.

Today, Adams lives just miles from the lynching site after a lifetime of running from the Ku Klux Klan, which he says tried to intimidate him into silence. At 81, he is the only known eyewitness to the murders and steadfast about what he saw. But he’s done talking about it and ready to leave it behind.

In the coming weeks, the GBI is expected to officially close its cold-case investigation opened in 2000. The agency learned recently that the FBI, which would not comment for this story, has quietly closed its case.

“We feel there’s a sense of hopelessness, that there is nothing left to pursue,” said GBI director Vernon Keenan. “The hope is that the official record of the investigation becomes public and becomes part of public history and that in turn may generate new information that can be pursued.”

This year, the GBI granted the AJC exclusive access to its 600-page case file, containing previously unreleased memos, interview transcripts and summaries.

The files reveal new details about the investigation, including that suspects of the lynching were members of the Ku Klux Klan, the white supremacist organization that terrorized thousands of African Americans through violence and intimidation. Among the disclosures:

- A major focus of the investigation centered on Adams' assertion that he saw a Georgia state police vehicle at the bridge during the lynching and that a state law officer actively participated in the killings. Agents concluded there was no supporting evidence to corroborate Adams' story.

- Agents gathered second-hand evidence about a man who allegedly saw a local law officer at the bridge during the lynching and that two young white boys were in a nearby field tending to a cow — both elements similar to the story Adams told in 1991. Both the alleged eyewitness and the minister who provided the information are now dead.

- Ku Klux Klan membership rosters unearthed by investigators nine years ago provide circumstantial evidence that the racist group may have played some role in the killings. The rosters from the Walton County Klan date back to the 1930s and 1940s and include names of four men who were suspects from the original 1946 FBI investigation. The rosters list a fifth man as having been the "Exalted Cyclops" of the local Klan chapter in 1939. The Klan leader also owned the white funeral home that recovered and handled the murder victims' bodies before they were transferred to a black-owned funeral home.

- The only time agents thought they had a major break in the modern case came in 2008. An informant told them a woman had revealed that her father had participated in the killings and had said guns used in the crime were buried on her land in Walton County where the Klan had allegedly plotted the murders. Some two dozen law officers spent two days digging up the property, but the tip proved to be faulty and no meaningful evidence was recovered.

- At least four main suspects from the original 1946 investigation were living when the case was reopened in 2000 and agents interviewed three of them. All were elderly men at the time and denied involvement in the killings. The fourth suspect refused to be interviewed. All the men have since died.

The GBI file documents thousands of hours state and federal investigators spent after the case was reopened, with the bulk of the work occurring in the latter half of 2000 and early 2001. A summary report written at that time concluded there was no new evidence to warrant a prosecution. The last interview of a possible suspect occurred in 2013 after a relative implicated a man, but the allegations didn't pan out.

The agencies have concluded that all known suspects are dead.

Earlier this month, Waymond Mundy, chair of the Moore’s Ford Memorial Committee, walked along the riverbank near where the murders occurred. The committee formed 20 years ago to memorialize the victims and promote healing.

Mundy said he has trouble accepting there’s no hope for the truth to come out when so many people from the community were involved.

"With something like this, this is horrific," he said. "Words can't (express) deep down inside how a person feels. I'm just numb."

Then, he added: “Nothing was ever solved here.”

‘A terrible point in the history of law enforcement’

For all that remained unresolved in the decades after the brutal deaths of Roger and Dorothy Malcom, and George and Mae Murray Dorsey, the belief that local law enforcement officials played a part in the killings persisted. It was an operating premise that drew federal authorities to the original investigation.

At minimum, the known facts about the two couples’ final hours suggested the police played a passive role in what was a coordinated mob killing.

The lynching occurred within an hour after Roger Malcom had been released from the local jail where he had spent the previous 11 days for assaulting a white farmer. He had been freed by Walton County deputies after a white farmer and bootlegger, Loy Harrison, posted $600 bond. Harrison drove Malcom and the other three farmhands along the Highway 78, then along the county’s winding dirt roads toward his farm near Moore’s Ford.

At the river, an armed mob of two dozen white men, positioned at the bridge, overtook his vehicle, he later told investigators. Harrison was the only confirmed witness to the crimes and his story never added up. Almost from the start, agents believed he helped coordinate the killings. He told federal authorities that he didn’t recognize any of the men in the mob despite the fact that they weren’t wearing masks.

Keenan says the facts point to a tacit role by law enforcement as local authorities failed to protect the safety of a prisoner. And after the lynching, they did little to cooperate with the investigation, which ended when a federal grand jury returned no charges days before Christmas 1946. Keenan noted that police played a role in many lynchings of African Americans across the South during the Jim Crow era.

“It’s a terrible point in the history of law enforcement,” Keenan said. “That’s a page of history that this state does not need to forget.”

Adams added an explosive new element to the narrative when he told his story to an FBI agent in 1991 and to an AJC reporter the following year.

In addition to directly implicating Loy Harrison and three other local men as members of the lynch mob — all of whom were dead by 1991 — Adams said he was certain he had witnessed a Georgia Highway Patrol vehicle blocking the Moore’s Ford bridge. He said he saw the officer directly participate in the violence, although he never identified him.

If true, Adams story suggested a conspiracy that went beyond the local authorities. GBI investigators in 2000 and 2001 spent days trying to find evidence to verify or refute the claim. They reviewed photos of highway patrol vehicles from the 1940s. Agents concluded that the photos of state patrol vehicles from that period did not match the car Adams described seeing on the bridge.

Adams agreed that the vehicle photos in the GBI file do not resemble the patrol car he saw 71 years ago. But he remains convinced that the car he saw belonged to a state trooper.

“When I seen that siren on the fender and the light on top and a white streak around the car,” he said. “That’s the way I remember it. I don’t think I’m wrong.”

Both the FBI agent who interviewed Adams in 1991 and the GBI investigators who spoke with him in 2000 noted that they found him credible.

But as the GBI advanced its investigation, agents started to raise doubts about his story. They reviewed the original FBI file and noted that other witnesses gave descriptions of vehicles they saw headed in the vicinity of Moore’s Ford around the time of the killings. Not one person in the FBI file said they saw a police vehicle.

“It was something that, if true, needed to be exposed,” Keenan said. “We did not want anything in this case hidden.”

‘He knew who done it’

Still, when agents found evidence in 2001 that matched other elements of Adams’ story, there’s no record in the file that they dug deeper. According to the file, a local farmer, John Mundy, allegedly told family friends that he witnessed some of the events that day. Mundy was supposedly fishing near the Moore’s Ford bridge the day of the lynching and saw as many as 40 men — including a sheriff’s bailiff.

The bailiff and three other sheriff’s officials were suspects in the original FBI investigation.

Mundy reportedly said that he also saw two white boys in a nearby field, tending to a cow — a similar story to what Adams told. Mundy died in 1998 so investigators were unable to verify his story, which was relayed to them by a family friend.

Mundy’s nephew, Waymond, the memorial committee chair, said his father told him over the years that “Uncle John” had seen something at the bridge and knew some of the people in the mob.

Waymond Mundy said he and civil rights activist Bobby Howard approached his uncle near the end of his life to try to get the story. But once they arrived at his nursing home room, his uncle had a pensive expression on his face and didn't want to talk.

“He knew something but he didn’t want to say anything,” said Waymond Mundy. “He was afraid for his children.”

‘So scared they couldn’t hardly move’

The FBI ran into a similar climate of silence, fear and hostility throughout its investigation in 1946, raising questions about the truthfulness of what witnesses told them.

Dispatched by President Harry S. Truman, some 25 federal agents conducted more than 2,500 interviews over the course of five months. They identified more than 150 suspects, but they found no direct evidence linking any of them to the crime. Years later, many agents remembered the painstaking effort to get witnesses to cooperate in an atmosphere rife with mistrust.

Retired FBI agent Louis Hutchinson, who was in the Atlanta field office at the time of the lynching, told GBI investigators in 2001 about his frustration finding willing informants, according to a memo in the file. A chapter of Hutchinson’s memoir recounts how agents worked in teams in Walton County because of the hostile environment they faced from white residents.

“‘The Feds are riding today,’ was an expression we often heard,” he wrote. “Here was a place where fear and anxiety gripped a segment of society — a place where people were afraid or unwilling to talk.”

It was in this environment of fear and silence, that Adams’ friend, Emerson Farmer, spoke to FBI agents in 1946 and told them a story that contradicted Adams’ account years later — and later contradicted what Farmer told his sister-in-law privately. Farmer said nothing to the FBI about witnessing the killings or being with Adams, according to the FBI report.

He said he was on his porch with his parents when he saw cars drive by their house, which was about a third of a mile up a dirt road from the bridge. Soon after, Emerson witnessed Loy Harrison drive by carrying four black passengers. His car was followed by another vehicle.

Moments later, he heard the gunshots from the direction of the bridge. Shortly after the shots, Emerson told the FBI that he saw Loy Harrison and another vehicle drive back up the road past his house. The black passengers were no longer with Harrison.

Farmer died in the 1980s, before Adams went public with his story of witnessing the murders together. Farmer’s parents in 1946 told FBI agents a story that matched their son’s. Farmer and his father were considered significant witnesses.

In 2000, the GBI noted contradictions between what Farmer told the FBI in 1946 and what Adams told the FBI in 1991. Adams also told agents he rode his horse home after the lynching, but no one in the FBI file reported seeing a boy on a horse.

“By using the original FBI file of 1946, present day GBI agents have been unable to substantiate the claim that Clinton Adams was present and witnessed the murders,” their report said.

Two boys ‘watched them do it’

But a 2000 interview that Farmer’s sister-in-law gave the GBI also raises questions about what Farmer told the FBI in 1946.

Loudonia Wise described a visit to Walton County in the 1970s when Farmer drove her across the Moore’s Ford bridge and claimed to have witnessed the killings from a nearby field. He said he could still hear the screams of the victims and he had nightmares about the lynching.

Farmer also said he saw his father participate in the killings with the other men. Emerson did not mention being in the presence of a friend. Wise was certain Farmer said he was alone in the field, according to the GBI memo.

Recently contacted by the AJC, Wise said the GBI memo from her 2000 interview mostly sounded like what Farmer told her long ago — except the part where Farmer said he was alone.

“He said him and his little buddy friend watched them do it,” she said. “And they said they was so scared they couldn’t hardly move.”

She’s certain he told her he was with a friend when he saw the lynching. She couldn’t recall the friend’s name, but when asked if it was Clinton Adams, she said that sounded right. She had never met Adams.

Adams, for his part, said he is sure Farmer’s father was not at the lynching, and nothing in the original FBI report suggests he was a participant.

Emerson Farmer grew up to live a troubled life. He compiled a record of petty crime and physically abused his own family. Wise shot and killed him in the 1980s after one of his violent episodes, later going to prison for the murder.

“He turned out to be the meanest human being I’ve ever seen in my life,” she said.

‘I’m just tired of it’

The small tenant house where the Farmers lived, like the thriving cotton fields and so much else in Walton County at the time of the murders, is gone today.

On a recent fall afternoon, the peaceful waters of the Apalachee flowed under a concrete bridge that sits about 75 feet upstream from the original site of the rickety, wooden crossing. The graffiti under the new structure marks it as a gathering spot for teens and others seeking a hiding place to do things they don’t want others to see. The bending dirt road that Loy Harrison drove down toward the river as he carried the four victims to their deaths is now paved.

Just across the bridge, on the Oconee County side, stands a new gated community called River’s Edge, with a waterfall facade at the entrance resembling many of the subdivisions that dot the suburbs of metro Atlanta. But there is an eerie quality to the place for those who can’t forget what happened there.

Clinton Adams feels it when he surveys the tree line where he says he and Emerson Farmer lay all those years ago. During a recent visit, he looked out over what was the cotton field that he and his friend crossed when they heard the commotion at the bridge in 1946.

“We just run out through the middle,” he said. “We seen what was happening. We laid down. It all took over on its own.”

For years, his first wife, Marjorie, was the only person who knew his secret, according to Adams, and she later wrote a book about living with it. They moved several times around the South and Midwest as her husband lived with fear the Klan was watching him. They were in in Florida when he lost part of his leg in a farming accident in 1989, an event that he said eventually led him to talk to the FBI. In 1998, the Georgia House recognized Adams for his courage and willingness to pursue justice.

After his wife died in March 2003, Adams reconnected with his childhood sweetheart, Retha, who was widowed and living in Barrow County.

They married in May 2004 and for a brief time lived in Florida before moving back to her home near Winder. His faith in God has deepened in the years since he went public with his story, he said, and he is contented in a way he had not been all the years he was moving around the country.

He said he no longer lives in fear of the past, but the lynching still effects him when he talks about it. On a recent visit with a reporter he became emotional when read the narrative of the lynching that he told the GBI in 2000.

Adams and his wife pray each night before they go to sleep in their modest farmhouse. A recent prayer included the hope that he will forget what he saw.

“I’m just tired of it,” he said. “After 71 years it comes after me every year — never let me go. I’m going to ask God. He’s going to take it away from me.”

Mixed emotions

Penny Mack has a similar desire to leave the past behind.

She was born in 1963, but the lynching caused her family a lifetime of turmoil and pain. Her mother, Mattie Louise Campbell, was married to Roger Malcom and had a 2-year-old son with him at the time of the killings. At age 20, Mack’s mother had to identify Roger’s body after the mob disfigured him with bullets, Mack said.

After the lynching, her mother became restless, she said. She moved several times to try to escape the hurt — to Atlanta, Ohio and Florida before returning to Walton County. On one of those journeys, Campbell left the son she had with Roger with a family friend in Ohio out of concerns for his safety.

Mack said she grew up wondering why she had an older half-brother in Ohio. At an early age she heard the story of the lynching from her mother, but initially she didn’t believe it.

When the case resurfaced a quarter century ago, the publicity caused her mother additional anguish after a lifetime trying to let go. Mack became the public face for her mother as the effort to solve the case took on new life. Mack became involved with the Moore’s Ford Memorial Committee, formed to honor the victims.

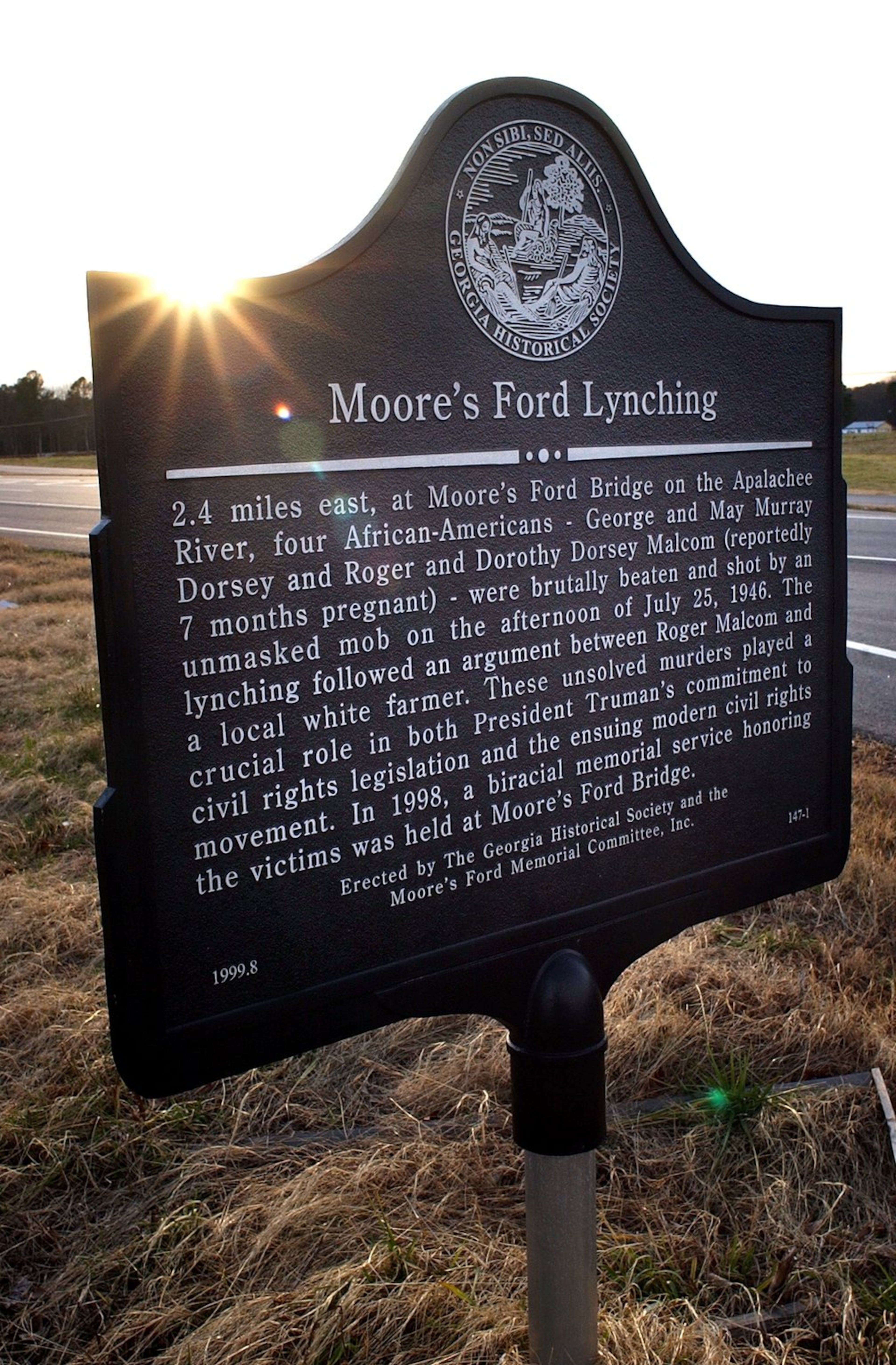

The committee grew out of the public interest in the case after Adams’ revelations. At the committee’s urging, the Georgia Historical Society in 1999 erected a roadside historical marker off Highway 78 not far from the site of the murders. The marker describes how four black citizens were “brutally beaten and shot by an unmasked mob.” It is one of a handful of public historical markers that acknowledge the hundreds of documented racial lynchings in Georgia’s history.

Mack said her mother forgave the men who killed her husband, but she died in 2000 without ever receiving justice. So, when an FBI agent visited Mack at her home in Athens in the past year it was a moment of mixed emotion. The agent delivered a four-page letter that outlined the agency’s investigative efforts and the decision, all these years later, to conclude the case.

The letter named known suspects and explained all were dead. It’s conclusion that there was no one left to hold accountable or prosecute is a difficult message for many to accept, but for Mack it provided some measure of peace.

“It hurts, but it made me feel good,” she said. “It brought some closure.”

For her half-brother, the young child who moved to Ohio, never again to live in Georgia, there was never such a resolution. Roger Malcom Hayes grew up to take the last name of his adopted family. He built a life and raised four children in Toledo, but he yearned to know his Georgia roots, according to his daughter Atanya Lynette Hayes.

He carried a small black-and-white photo of his birth father throughout his life. He worked for three decades as a repair technician for Pepsi fixing pop machines, and he was active as a minister and pastor in the church. He returned regularly over the past two decades to participate in efforts to memorialize the Moore’s Ford victims.

His daughter said when authorities reopened the case 17 years ago it provided “a ray of hope” after so many decades of quiet pain. Her father died suddenly in April 2016 after a brief battle with cancer. She believes he would not approve of authorities closing the case without any resolution. The lynching and the community’s silence about the identities of the killers remained an unresolved wound throughout his life, she said.

“He dealt with it and he put a bandage over it so he could live as normal a life as possible,” Ms. Hayes said. “I know it bothered him. Every time he talked about it you could see it in his face. His eyes would tear up. He felt helpless — like nobody would help him get justice for the murder of his father.”

How we got the story

AJC investigative reporter Brad Schrade gained access to the 600-page case file the Georgia Bureau of Investigation assembled in its investigation of the Moore’s Ford murders. The file contained interviews, memos and transcripts. Schrade also reviewed summaries of the FBI’s initial investigation into the crime in 1946. Schrade tracked down the lone surviving witness to the crime, Clinton Adams, and conducted extended interviews with him. Schrade also spoke to descendants of the murder victims and others connected to deceased witnesses.