Robert Graetz, white minister who supported Montgomery bus boycott, dies

As a young Lutheran minister in Alabama in the 1950s, the Rev. Robert S. Graetz Jr. would alternate his driving routes to thwart attackers. He once measured a 15-inch-deep crater left by a bomb that targeted his home in Montgomery. And to shield his young children from fear — and the shards of glass that would follow another explosion — he would play a “game” with them where they would crawl behind a couch when there was a suspicious sound outside.

»FROM JUNE: Dr. Thomas Freeman, debate coach who taught MLK at Morehouse, dies

Defying the menacing of the Ku Klux Klan, intimidation by the authorities and isolation among fellow clergymen, Graetz remained a rare, unbowed voice for desegregation among white people in Alabama, supporting the Montgomery bus boycott that transformed the nation’s budding civil rights movement.

»FROM JUNE: Legendary entertainer Carl Reiner dead at 98

“I have always contended that the absence of fear is not the point,” Graetz wrote in “A White Preacher’s Message on Race and Reconciliation: Based on His Experiences Beginning with the Montgomery Bus Boycott,” a memoir published in 2006. “What you do when you are afraid is what makes the difference. We often had good reason to be afraid.”

Graetz, who seemed to toggle seamlessly between foot soldier and field general in civil rights and social justice causes for roughly seven decades, died Sunday. He was 92.

»FROM MAY: Remembering the troubled actor Dennis Hopper, 10 years after his death

Graetz had Parkinson’s disease and had been in hospice care in recent months. Kenneth Mullinax, a friend and a family spokesman, confirmed the death, at Graetz’s home in Montgomery.

Advocate for equality

Graetz never possessed the international prominence and presence of a friend, the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., nor the through-the-ages symbolism of a neighbor, Rosa Parks. But Graetz, as the pastor of Montgomery’s all-Black Trinity Lutheran Church, was a forceful advocate for equality, accepting scorn and derision for a stand now seen as among the most principled of a turbulent era in Alabama’s segregated capital.

»THE CIVIL RIGHTS ERA: An American tragedy — the lynching of Emmett Till

The bus boycott began less than six months after Graetz arrived in Montgomery, following the arrest of Parks. Although word of her detention spread quickly through the city’s Black neighborhoods, Graetz, a newcomer, did not know what had happened until another minister alerted him to burgeoning plans for a protest.

Graetz telephoned Parks, a neighbor who sometimes led NAACP activities at his church, to inquire about the anticipated demonstration. Only then did he learn that it was her arrest that had prompted the action.

»FROM FEBRUARY: David Roback, co-founder of alternative rock band Mazzy Star, dead at 61

Graetz and his wife, Jeannie, elected to aid the boycott, in part to remain effective in their new church. The pastor used his Sunday sermon to urge parishioners to avoid Montgomery’s buses on Monday and offered rides to work. He spent Monday morning driving Black residents and then went to the courthouse, where the norms of segregation forbade him from sitting in the “colored” section during Parks' swift trial.

The boycott, first planned as a one-day event, did not end quickly, and Graetz continued to drive Black residents. Although some white ministers privately endorsed the desegregation effort, public gestures of support were met with condemnation and quick dismissals from their congregations.

»FROM AUGUST: Remembering Jerry Garcia 25 years after his death

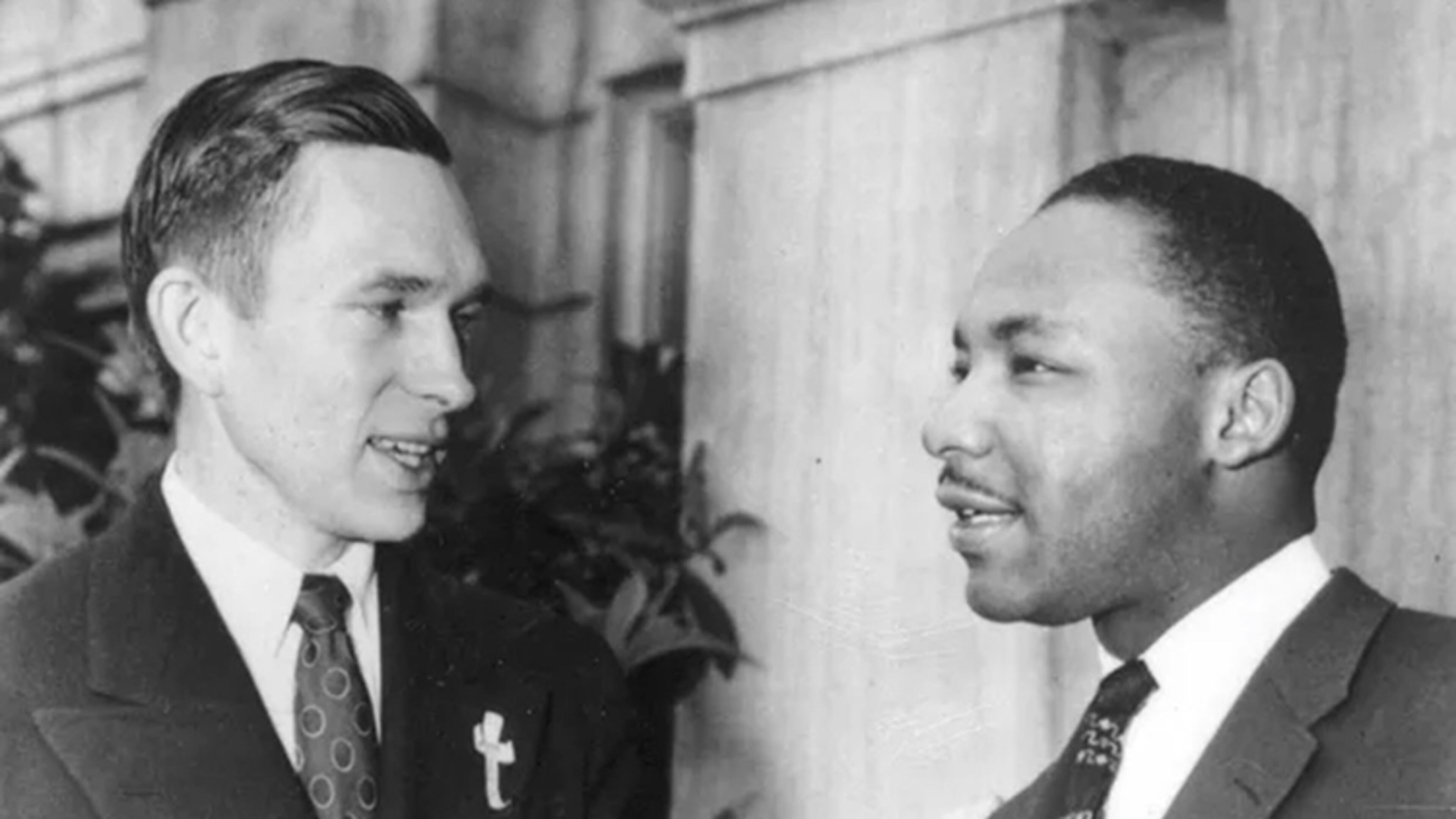

Not Graetz. He appeared with King at the courthouse while wearing a cross that read “Father, Forgive Them” — and was pictured on the front page of The New York Times doing so — and became so well known that The Montgomery Advertiser asked him what it was like to live as a pariah.

“I don’t know any pariahs,” he replied.

But Graetz’s activism and closeness with Montgomery’s Black residents made him a target for white supremacists, including members of the Ku Klux Klan. In August 1956, the boycott having already stretched more than eight months, the parsonage where Graetz lived was the target of a bombing. The pastor and his family were traveling in Tennessee at the time of the attack, which Montgomery’s mayor suggested was a publicity stunt by supporters of the bus boycott.

The boycott ended in December 1956, just over a year after it began, but anger continued to simmer. In January 1957, while the Graetz family, including a newborn, slept, a bomb exploded outside their home at 2 a.m. Again, no one was injured. Parks later memorialized the attack in notes that the Graetz family purchased at auction in 2018 and donated to Alabama State University, a historically Black institution in Montgomery.

Although the authorities made arrests in connection with the attacks, the suspects were acquitted, Graetz thought, because the all-white juries begrudged him for helping Black residents.

“If anything, a white person who was helping a Black person was seen as worse than the Black person,” he recalled in an interview in August 2018.

He found particular solace in the 27th Psalm, which includes the verse, “Though an army besiege me, my heart will not fear; though war break out against me, even then I will be confident.”

Early life

Robert S. Graetz Jr. was born in Clarksburg, West Virginia, on May 16, 1928. His family, with a lineage of Lutheran clergymen, typecast him early as a future minister, with his paternal grandfather addressing him in German at seemingly every opportunity and often speaking to him at an early age about a life in the church.

Growing up in the West Virginia of the Great Depression and World War II eras, the boy attended segregated schools and, as he acknowledged in his memoir, most likely referred to Black people as “colored people.”

He considered a career in medicine but enrolled at Capital University, in Columbus, Ohio, as a pre-theological student. It was in the late 1940s at Capital that he became interested in civil rights, after preparing a sociology course term paper that explored inequality in education. He soon founded a race relations group for the campus and joined the Columbus chapter of the NAACP, taking the streetcar to meetings.

He married Jeannie Ellis, with whom he had seven children, in 1951. She survives him. A complete list of survivors was not immediately available.

The couple moved to Alabama in 1955 and lived in Montgomery for several years — Graetz was even a groomsman to Fred Gray, Parks' lawyer — before the pastor took a position at a church in Ohio. Before the family moved there, King and his wife, Coretta, brought them a gift of a silver serving tray. Even in recent years, the tray remained in a place of honor at Graetz’s home in Montgomery, where the couple lived in semiretirement and routinely met with student groups and participants on civil rights pilgrimages.

“We feel God has given us the unique privilege of standing with one foot in the Black community and one foot in the white,” he wrote in his memoir. “It may not be comfortable, but that is where we are. And until God tells us it is time to slow down, we intend to keep pressing ahead with our witness.”

Before Graetz first went to Alabama, church officials, he wrote, “made me promise to focus on being a pastor and not to start any trouble in Montgomery.”

Considering the admonition decades later, Graetz said in his book, “I still believe I kept my promise!”

He never made trouble, he would say wryly. He only joined it.