Georgia medical board easy on opioid violators

Dr. Nevorn Askari started out as a pediatrician, not a drug dealer.

But after getting busted for Medicaid fraud, this Emory University-trained doctor chose another path. She accepted a part-time job at a “pain clinic” operating out of a rundown Atlanta house.

She saw 40 patients a day and most left happy, even though they waited hours for exams and spent only 5 or 10 minutes with the doctor once she arrived. Askari knew they didn’t come hoping for a long chat about their symptoms.

“They were there to get pain medication,” Askari told a jury earlier this year.

It was common for patients to tell the doctor what they wanted, as if they were ordering off a restaurant menu. And almost always, they got it. “The specific drugs that were usually requested [were] oxycodone,” Askari testified.

Some pharmacists refused to fill her prescriptions. Federal and state agents starting nosing around. Georgia’s medical licensing board was flooded with complaints, according to court documents.

Even so, Askari kept practicing for years before she was arrested – and for years after her arrest, too. Even following her guilty plea, the medical board permitted her to work at her own clinic, where she promoted the use of natural remedies and alternative treatments. The board restricted the medications Askari could prescribe only after a federal judge had already imposed limits.

When she finally gave up her license, just weeks before she checked into prison in October, there was no mention in her voluntary surrender document posted on the board’s website of why she was turning in her white coat.

Over the past decade, the state death toll from opioid-related overdoes has exploded, last year claiming 982 lives. Many more could have died: Emergency workers in Georgia administered opioid overdose-reversing medications nearly 10,000 times last year. To attack the epidemic, Georgia this fall formed a statewide opioid task force whose goals include taking a hard line against doctors who deal.

But an investigation by The Atlanta Journal-Constitution found that the arm of state government charged with protecting the public from dangerous doctors — the Georgia Composite Medical Board — rarely yanks the licenses of physicians who behave more like dealers than healers.

Years into the opioid crisis, the Georgia board has taken public action against only a handful of doctors a year for improper opioid prescribing, the AJC found in a review of board actions since 2011. In almost every case, the doctor-dominated board allowed the errant prescribers to keep seeing patients, even if they have recklessly prescribed pain killers or been arrested on drug charges.

"I get very frustrated with the Composite Board of Medicine that they're not doing more to reel in some of these physicians who are obviously out of control," said U.S. Rep. Buddy Carter, R-Ga, a licensed pharmacist who is a member of a House committee that is focused on the national crisis.

Routinely, the board "punishes" doctors with prescribing problems by requiring them to take a prescribing course. In cases where a doctor has been arrested, the board too often sits back and waits — sometimes for years — until a criminal case ends, allowing the doctor to practice in the meantime.

Yet one doctor who goes rogue can create or sustain hundreds of addicts.

Only this year did the medical board come up with its own version of a crackdown: requiring every doctor in the state to take a class about the danger of opioids and the hallmarks of addiction.

Blatant pill mills shut down

As patients got hooked on opioids, it created a new opportunity for doctors willing to trade in their Hippocratic oath for cash, sex or just a crowded waiting room.

Early on, the worst went to work in sketchy, cash-only "pill mills" that opened all over Georgia once Florida cracked down.

"It was kind of like all of the sudden, here within a period of a few months, we almost had an epidemic of these pill mills popping up everywhere and doing their thing," said Dr. E. Dan DeLoach, a plastic surgeon from Savannah who is chairman of the Georgia board.

Georgia passed two laws to deal with the problem: in 2011, authorizing a pill-tracking database to identify patients getting too many opioids, and in 2013 restricting who could operate a "pain clinic" and requiring these clinics to get licensed.

The laws have helped get rid of some blatant operations that attracted people from outside of Georgia to get their fix.

By early 2014, clinics in Valdosta and Columbus where Drs. William Bacon and Donatus Mbanefo worked were shut down. The clinics had drawn hundreds of out-of-state patients and in less than three years had issued prescriptions for 2.5 million oxycodone pills, as well as hundreds of thousands of doses of other opioids. Bacon gave up his license in 2014. Mbanefo kept his until May 2016 — three months after he and Bacon were indicted on felony drug charges in a federal case.

But improper prescribing has continued across Georgia. Recent cases suggest any type of doctor — from a big-city psychiatrist to a small-town family doctor — can turn into a local candy man.

In Clayton County, for example, Dr. Narendra Nagareddy, a psychiatrist, is now facing felony murder charges in the overdose deaths of six patients. Just this past October, federal authorities charged Dr. Joe Burton, a prominent former medical examiner in metro Atlanta, with illegally distributing opioids in a drugs-for-sex case.

Board remains mum

The medical board should be on the front lines of fighting the opioid crisis. After all, the board can suspend a doctor’s license quickly if it believes the public is in danger.

But the AJC’s investigation raised questions about whether the board had the authority, the resources or the will to identify the doctors who are overprescribing — and deal with them.

Consider the criminal cases, the ones where the doctors were charged as drug dealers.

Dr. George Mack Bird III, a gynecologist, was first arrested in 2015 on drug charges. The board just suspended his license, through a consent order, last month. His criminal case is pending.

Such delays are typical.

Dr. William Richardson, who worked for the same pill mill operation as Askari, was arrested in 2013. A judge restricted his prescribing as a condition of bond, but the medical board took no public action. Finally, he voluntarily gave up his license this past June, right before he went to prison.

After cops discovered Dr. Edd Colbert Jones III was writing prescriptions for oxycodone and other drugs that his girlfriend, an addict, was filling and selling, he was arrested in 2015. As the case unfolded, more charges were filed. All the while, the board allowed the family medicine doctor to stay in practice with the condition he take a class on prescribing and log his prescriptions. When he was sentenced this past April, it was prosecutors who required him to give up his medical license.

The board does publicly discipline some doctors in prescribing cases that involve no criminal charges. With no judge bringing the hammer down, it’s all up to the board.

In those cases, drastic measures are rare. A course through Mercer University often gets a doctor out of trouble with the medical board, the AJC found.

Last year, the board found Dr. Rahim Gul from 2005 to 2008 had improperly prescribed opioids such as hydrocodone and usually also prescribed a benzodiazepine, such as Valium or Xanax — a potentially dangerous combination. Gul was ordered to get out of pain management, pay a fine and pass a prescribing course before being allowed to again prescribe highly addictive painkillers.

After one of Dr. Steve Dennis Daugherty’s patient died of an accidental overdose in 2009, the board found the osteopath prescribed excessive amount of methadone, an opioid used for pain and in drug detox. The prescriptions were given to the patient, who suffered from back pain, even though the patient’s mother, at least two pharmacists and a pharmacy benefits manager all called Daugherty with concerns. In 2014, the board required him to take Mercer’s prescribing course and banned him from treating pain patients and prescribing methadone. But it allowed him to stay in practice. His Georgia medical license is now listed as inactive.

Daugherty told the AJC he felt the board did not treat him fairly and that he was simply trying to help the patient get relief from pain. The doctor also said the patient died primarily of alcohol poisoning, and the board’s decision acknowledges that the patient told him she was not using alcohol.

The board waited four years after holding a hearing on the case to make its decision, he said, and then applied new standards that weren’t in place when he was treating the patient. “I’m not sure to this day what I am being punished for except being a political example,” Daugherty said.

Slow justice

The board won’t explain its rationale for individual cases — it’s legally barred from discussing its investigations and even its final decisions.

But DeLoach says the board looks at allegations and takes steps with patients in mind. "We the medical board are doing everything we can to protect the patients by censoring what kind of prescribing authority these physicians may have and censoring some of the types of patients they may see and censoring the kinds of procedures they can peform," he said.

Karl Reimers, the board's director of investigations and enforcement, said the board has assigned one of its investigators to the DEA's Drug Diversion Squad. The medical board is also part of the new opioid task force, created in September by Attorney General Chris Carr.

The board acknowledges, though, that its wheels of justice turn slowly.

The board has six agents to work the 2,200 investigations it handled last year, about a fourth of which involved prescribing issues. A single prescribing case can take up to a year for the board to process, by the time the board gets a subpoena to access the prescription database and another subpoena to obtain medical records of patients that must be reviewed, interviews all the parties and reviews data, Reimers said.

“We have plenty of work,” he said.

Plus, the board relies primarily on complaints to find out about doctors who are improperly prescribing. The board is not routinely alerted when a Georgian overdoses on prescription drugs. “If we have prescription bottles, it will be documented, but we do not notify the medical board,” said Nelly Miles, a spokeswoman for the Georgia Bureau of Investigation, which conducts autopsies in overdose deaths.

A new Georgia law may allow the board to receive alerts from the state’s pill-tracking database about doctors who are high prescribers. The board in the past was barred by state law from tapping into the database without a subpoena. Even with the new law, the board said last week it is likely to stick with the current approach and get subpoenas before looking at a doctor’s record.

A case drags on

In 2015, one of the physicians the Georgia board did examine was Dr. Harvey Leslie, who specializes in pain management.

The Decatur doctor was one of the top prescribers of oxycodone-acetaminophen in Georgia in 2015, according to Medicare prescribing data analyzed by Pro Publica. In its review, the board found he prescribed high doses of opioids along with other medications to a patient who repeatedly tested positive for illicit drugs that included cocaine.

By continuing to prescribe opioids to a habitual drug user, the board said the doctor failed to meet standards. A board expert who reviewed the case was blunt, describing Leslie as a “drug dealer in a white coat.”

“That’s derogatory and inflammatory,” Leslie told the AJC. “None of my patients ever overdosed.”

Leslie said he doesn't believe in refusing to see patients with addiction issues. "Narcotic abuse is a disease," he said. "It's like saying if a patient has diabetes, don't treat it. It would be wrong for me not to treat the patients on crack cocaine."

Leslie said he felt he could help the patient by weaning her off strong narcotics and helping her eventually stop using cocaine. The patient whose care was being scrutinized testified for Leslie, describing him as a “wonderful” doctor.

Leslie also said the board passed its detailed rules on pain management protocols after the time he was treating the patient between 2009 and 2012. “They went and retroactively found me guilty of improper prescribing,” Leslie said.

An administrative law judge said the doctor’s “actions reflect inadequate training rather than deliberate misconduct” and recommended he be banned indefinitely from prescribing controlled substances.

The board took the recommendation last year and ordered Leslie to take the Mercer prescribing course. The decision allowed Leslie to remain actively licensed. But the board has refused to fully reinstate his prescribing privileges, limiting him to only the least dangerous drugs. While he can’t prescribe opioids, his office still sees pain patients. He said other doctors who work at his office handle prescribing. Without being able to prescribe pain medications, Leslie said, it’s hard for him to do his job.

"I'm like a Walmart person," he told the AJC, "I'm like a greeter."

Doctors fight new rule

One reason the board moves cautiously is because of worries that well-intentioned doctors will be caught up.

"The overwhelming majority of physicians are out there trying to do a good job and help their patients and keep them out of pain and keep them comfortable," DeLoach said. "I hate to see us start down a slippery slope where we're going to start looking and scrutinizing every physician as to how much pain meds they are giving, and now all of the sudden you've got the pain cops coming in and saying 'Well, doctor, you ordered too many Tylenol Number 3s this month, we're going to have to take you downtown.' You hate to see that sort of thing started."

Doctors for years were under pressure to do a better job at treating pain, and they were told that opioid drugs weren’t highly addictive. And while the board for years has alerted doctors about the opioid abuse problem, and federal authorities also were sounding the alarm, DeLoach said that it’s only become clear in the past year to many physicians that their prescribing may need to be dialed back.

So the board has focused primarily on educating, rather than punishing, doctors. In August, the board passed a rule requiring every doctor to take a course on prescribing before renewing their license — though the measure was opposed by the Medical Association of Georgia, a powerful doctor lobbying organization.

That board mandate, and a new law requiring doctors to check the prescription monitoring system, are about "trying to make physicians aware that we have been traditionally taught to prescribe too many pain medications for patients," DeLoach said.

Plenty of people do argue against much interference with doctors or tough sanctions.

Page Pate, an Atlanta attorney who has represented doctors accused in criminal prescribing cases, said education and administrative action, not prosecution, should be the approach. Most of his clients, he said, had never been warned they needed to cut back on opioids. “Not a single solitary medical person questioned their decision, for the most part, until the DEA raids their clinic and prosecutes them on what is an incredibly vague standard,” Pate said.

But Dr. Craig Weil, a Marietta hand surgeon who is pushing for reduced opioid prescribing, said the medical board and others in state government need to change the approach when they find a doctor who is prescribing improperly, given the evidence that doctors are playing such a large role in the opioid crisis.

“That leniency [in discipline] is not sustainable and is obviously wrong,” Weil said. “It’s wrong for patients and wrong for other physicians who try and do things in the correct way.”

Given the magnitude of the problem, and the fact that too many doctors are still falling back on the “simplicity of writing a prescription,” Weil said a tough stance with oversight and rules makes sense.

"To me it's less about trying to clamp down on physicians or put them under the microscope," Weil said. "I think it's really much more about trying to protect patient care and from that standpoint – who can argue against that?"

Seeking a tougher stance, State Sen. Renee Unterman, a Republican who chairs the Health and Human Services committee, earlier this year pushed a bill that would have allowed criminal charges against doctors who refuse to check the state’s prescription database. The legislature passed a more lenient bill instead, letting the medical board deal with those doctors.

Georgia doctors who have resisted tough new regulations, Unterman said, should instead challenge their over-prescribing colleagues and talk to the parents of patients who have overdosed.

“They need to police their own industry,” Unterman said. “It’s the 1 percent you have to police and get rid of the bad apples. If their own industry doesn’t get rid of the bad apples, who does?”

Protecting doctors’ rights

The board said that when considering disciplinary action, it’s important to protect a doctor’s right to due process. But when investigations and cases go on for years, the board often continues to wait.

Dr. Askari got on the board’s radar following her conviction for Medicaid fraud, and it put her on probation. But after the board lifted her probation in 2008, it apparently heard a lot more.

According to a document filed by prosecutors in the federal pill mill case, the board received more than 10 complaints about Askari between January 2010 through August 2012.

The complaints alleged that the doctor was “prescribing controlled substances to teenagers, addicts and ‘doctor shoppers.’ ” The complaints also said she was prescribing to patients she did not see, directing employees to lie to pharmacists and even submitting false information about vaccines to the state.

Yet the board didn't take action until the cops arrested Askari. Even then it didn't take her license. It waited until this past June, after she was sentenced to 66 months in prison.

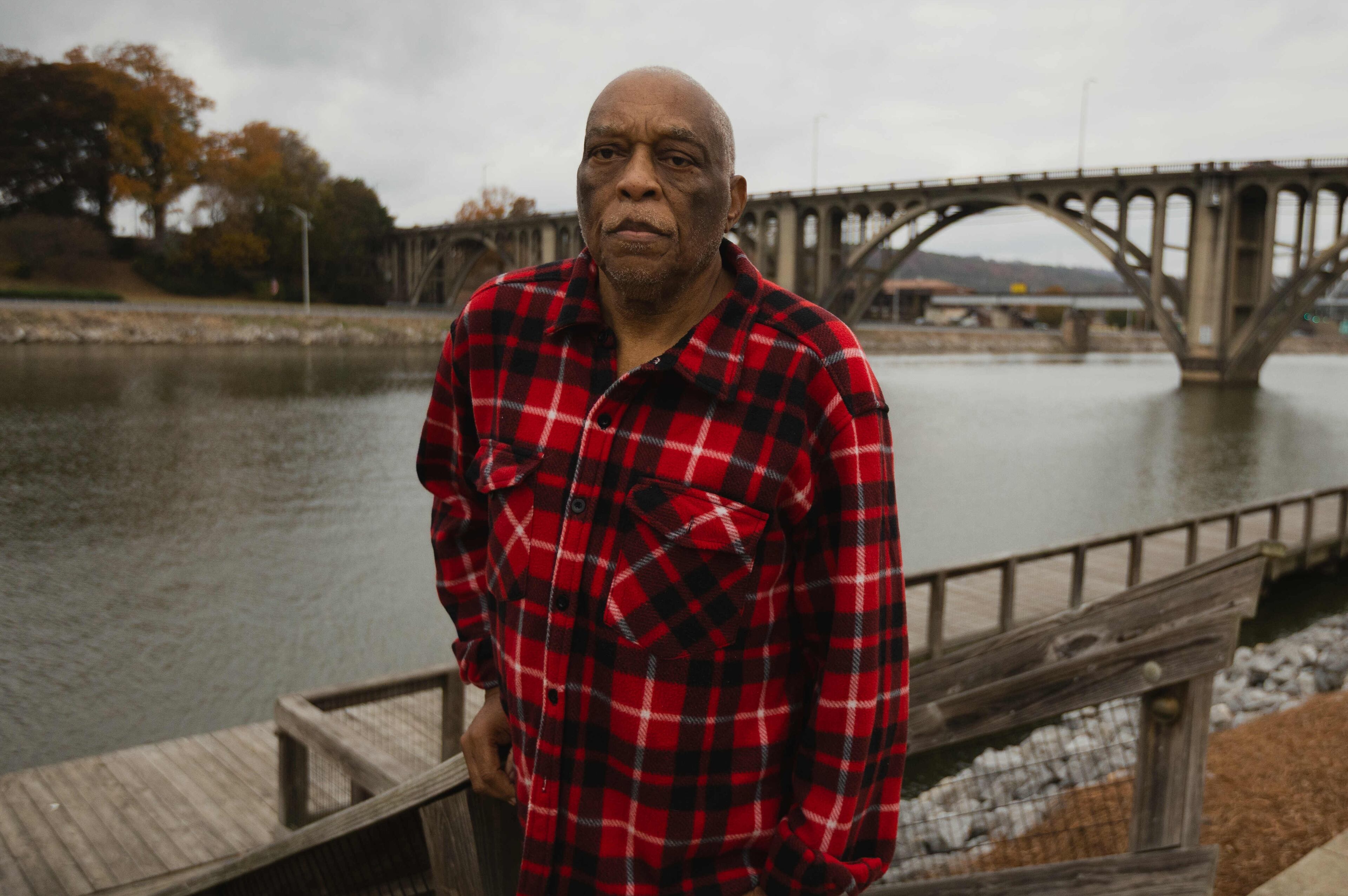

Addicts who relied on the pill mill where Askari worked testified about how opioids had ruined their lives. One mother’s children were taken away from her, another said she nearly died from overdosing, a man who came from Alabama to get his prescription pills said he ended up in jail before eventually getting clean.

Askari said in court that it took her two years to realize that she was working at a pill mill, and she worked there another six months before leaving the clinic that the drug agents were investigating.

When asked why she finally left, Askari testified: “I just felt like the way that we were practicing medicine there was just not ethical.”

The AJC found that doctors nationwide continue to overprescribe opioids. Read the national investigation here: myAJC.com

» Read the AJC's award-winning investigation, Doctors & Sex Abuse: AJC 50-state investigation