Commentary: School vouchers would exclude many students

Public schools are the great equalizer in our increasingly segregated nation. As the gap between rich and poor widens and uninformed bigotry flows freely, public schools remain a bastion of hope for a democratic society purportedly dedicated to the public good.

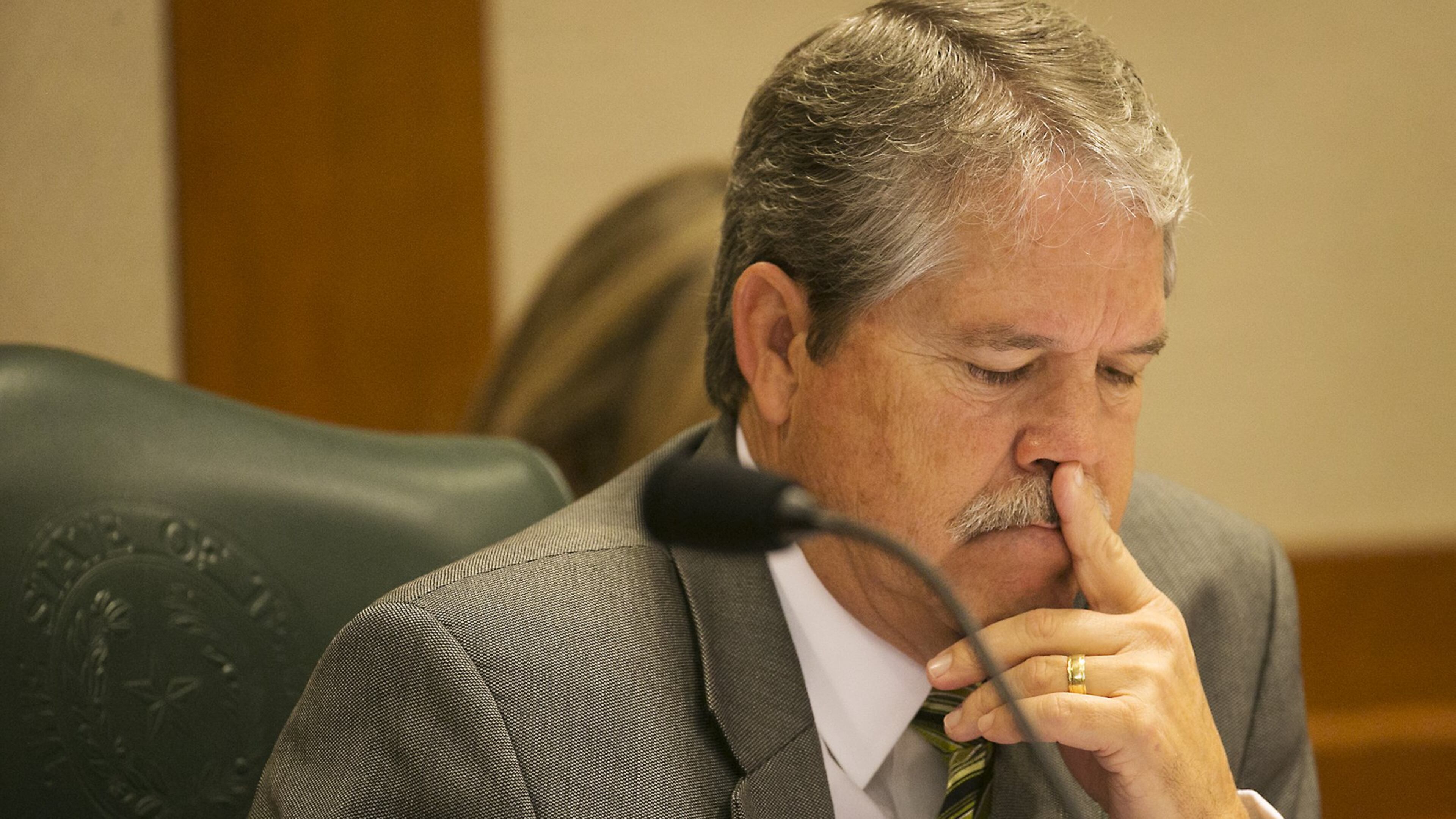

Recently, the Texas Senate approved a bill allowing vouchers offering public money to children attending private and religious schools in communities with populations over 285,000. Republican Sen. Larry Taylor, the bill’s sponsor, wishes to “create state-subsidized education saving accounts for parents while offering tax credits to businesses that sponsor private schooling via donations.”

At Mathews Elementary in Austin, where I’m an intern, I am struck every day by the power and importance of truly integrated public schools. Mathews is located in wealthy, white West Lynn neighborhood. The 100-year-old school is surrounded by beautiful homes, parks, a public swimming pool, and our beloved Graffiti Castle. Many of the neighborhood students attend Mathews, as do the children living in our downtown Salvation Army Shelter and many of the children of the University of Texas’ international students.

Our school is incredibly diverse, consisting of immigrants, students with special education needs, students experiencing homelessness, and students from numerous socioeconomic, racial and religious backgrounds.

Groups of children bustle down the hallway, their laughter filling the room, their energy, contagious. They form close friendships, pair together for group projects and eat their lunch together in the cafeteria. These students are crossing race and class lines that many of us rarely do — and some never have. Pre-K children are learning lessons of empathy and understanding that will last beyond the classroom. Public school is providing these students with deeply valuable knowledge and compassion.

When considering public policy, we must remain conscious of our nation’s shameful history of discrimination against people of color and the poor. In Nikole Hannah-Jones’ New York Times article titled “Have We Lost Sight of the Promise of Public Schools?”, she explores the bargains struck in the FDR-era: “To get his New Deal passed, Roosevelt compromised with white Southerners in Congress, and much of the legislation either explicitly or implicitly discriminated against black citizens, denying them many of its benefits.” Public, at that time, meant white Americans only.

And so, as Jim Crow eventually faded and black Americans were formally given access to many of our public institutions, support from white communities quickly faded. Instead of integration, there was privatization and withdrawal. White communities began fighting the expansion of public transportation, public housing became stigmatized, and white children began attending private schools or moving to neighborhoods with majority white families.

As the meaning of the word “public” changed from white Americans to all Americans, white America was no longer invested in the public good. Today, even after the privatization of schools, the creation of charter schools, and the segregated drawing of school district lines, we’re trying to disinvest even more.

When those with power and money retreat from public education, “public” no longer means all of us.

Our democracy relies on a social contract where we are all invested in the public good — even if we don’t have to be. Senator Taylor’s bill lights this contract on fire. Do we want to keep that contract alive or let it burn?

Rooke-Ley is a graduate student in the UT Austin School of Social Work and an intern at Mathews Elementary school.

More Stories

The Latest