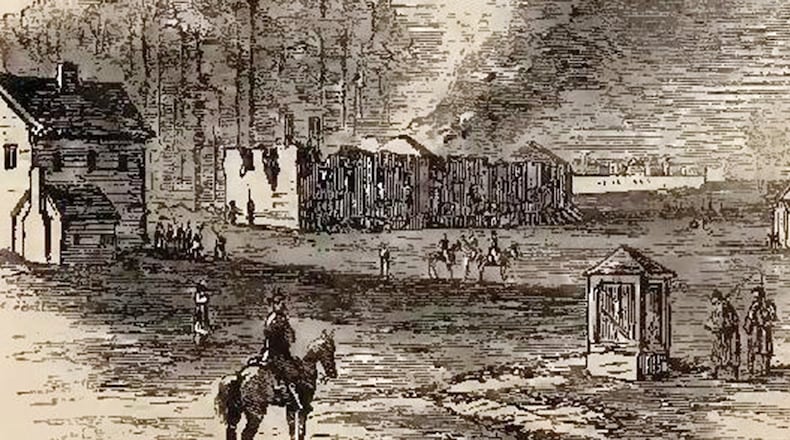

“Behind us lay Atlanta, smouldering and in ruins, the black smoke rising high in the air, and hanging like a pall over the ruined city.”

So observed Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman as he paused for one last glimpse of the land he had conquered. Sherman rode out of Atlanta on Nov. 16, 1864, to join Maj. Gen. Henry Slocum’s “Army of Georgia” — the left wing of the Federals’ March to the Sea.

Following the Decatur Road east out of Atlanta, Slocum’s wing joined the march the Federals, 62,500 men strong, had started the previous day when Maj. Gen. Oliver. O. Howard’s right wing took a southward route leaving the city.

Confederate officials issued pleas to civilians to turn out to resist Sherman’s force.

Gen. P.G.T. Beauregard, from his headquarters in Corinth, Miss., called on Georgians, “Arise for the defense of your native soil! Rally around your patriotic Governor and gallant soldiers.” Sen. Benjamin Hill urged his constituents to “Put everything at the disposal of our generals … be firm … act promptly, and fear not!”

Georgia Gov. Joe Brown, not quite sharing the confidence of Beauregard and Hill, sent a dispatch to President Jefferson Davis informing him that “we have not sufficient force” to resist the enemy advance toward Macon. “I hope you will send us troops as re-enforcements till the exigency is passed.”

Davis had no additional troops to send to Georgia. But he took steps to ensure the state at least received a bounty of martial brainpower. He ordered Gen. Braxton Bragg to Augusta, and Beauregard called for Lt. Gen. Richard Taylor to make his way toward Macon. Already in the state were Maj. Gen. Howell Cobb in Macon; Maj. Gen. G.W. Smith, who commanded the Georgia militia; Georgia’s Adj. Gen. Henry Wayne; and Lt. Gen. William Hardee guarding Savannah.

Advancing into Madison on Nov. 18, Federal soldiers in the left wing noted the town’s beauty — and then applied the torch to the railroad station, along with destroying other structures deemed of military value.

One soldier described his unit’s entrance into Madison. He witnessed several homes with the “blinds half raised … while the bands were playing ‘Dixie,’ but as soon as it struck up ‘Yankee Doodle,’ they were suddenly dropped and slammed to.”

The Northern troops rushed into Madison’s businesses and helped themselves to whatever they could carry — including, as one officer witnessed, “a piano, (which) was a prized article of capture.” The troops later burned the keyboard before leaving the town. One of the last soldiers to depart remarked, “The wreck of Madison was pretty effective.” Incidents like this would replay throughout the march.

The Federals feinted toward Macon but then veered off to the east. On Nov. 22, after the balance of the right wing had bypassed the city, Confederate Brig. Gen. Pleasant Philips led 2,400 soldiers — mostly militia and local defense troops — out of Macon toward Augusta. (Officials feared Augusta, home of the Confederacy’s Powder Works, would be Sherman’s next target.)

That day, outside the burned village of Griswoldville about 10 miles east of Macon, the major infantry engagement of the campaign took place. Believing he could defeat the rear guard of the Federal force, Philips threw his troops against the fortified position of Brig. Gen. Charles Walcutt. The Southern force outnumbered the bluecoats, but Walcutt’s soldiers held the high ground, and many carried repeating rifles.

The combination of rapid-fire weapons, artillery and terrain proved too much for the attackers. When the smoke cleared, 650 of them — teenagers and old men who made up the militia — lay dead or wounded on the field. Col. Robert Catterson with the 97th Indiana Infantry, the regiment anchoring the Federal right during the battle, wrote of the charge in his post-action report: “On came the enemy, endeavoring to gain possession of a ravine running parallel … to our front … but the fire was so terrible that ere he reached it many of his number were stretched upon the plain.”

While the fighting played out in Griswoldville, lead elements of Sherman’s left wing began entering the state capital of Milledgeville. The evening of Nov. 22, Sherman made his headquarters at “Hurricane” — the plantation home, it turned out, of the aforementioned Howell Cobb.

Cobb was one of antebellum Georgia’s preeminent statesmen, having served as governor, U.S. congressman and speaker of the House. He was secretary of the Treasury in the Buchanan Administration. Also, he presided over the 1861 convention of secession in Montgomery, Ala., that led the South out of the Union. After learning the identity of the owner — in Sherman’s eyes, a detestable traitor — Sherman sent orders to Maj. Gen. Jefferson C. Davis: “Spare nothing.” Cobb’s property was stripped bare and burned.

In Milledgeville the following day, Federal troops would replicate the storm stirred up on Cobb’s plantation.

Michael K. Shaffer is a Civil War historian, author and lecturer. He can be contacted at: www.civilwarhistorian.net

For more on the Civil War in Georgia, follow the AJC: http://www.myajc.com/s/battleofatlanta/

About the Author

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured