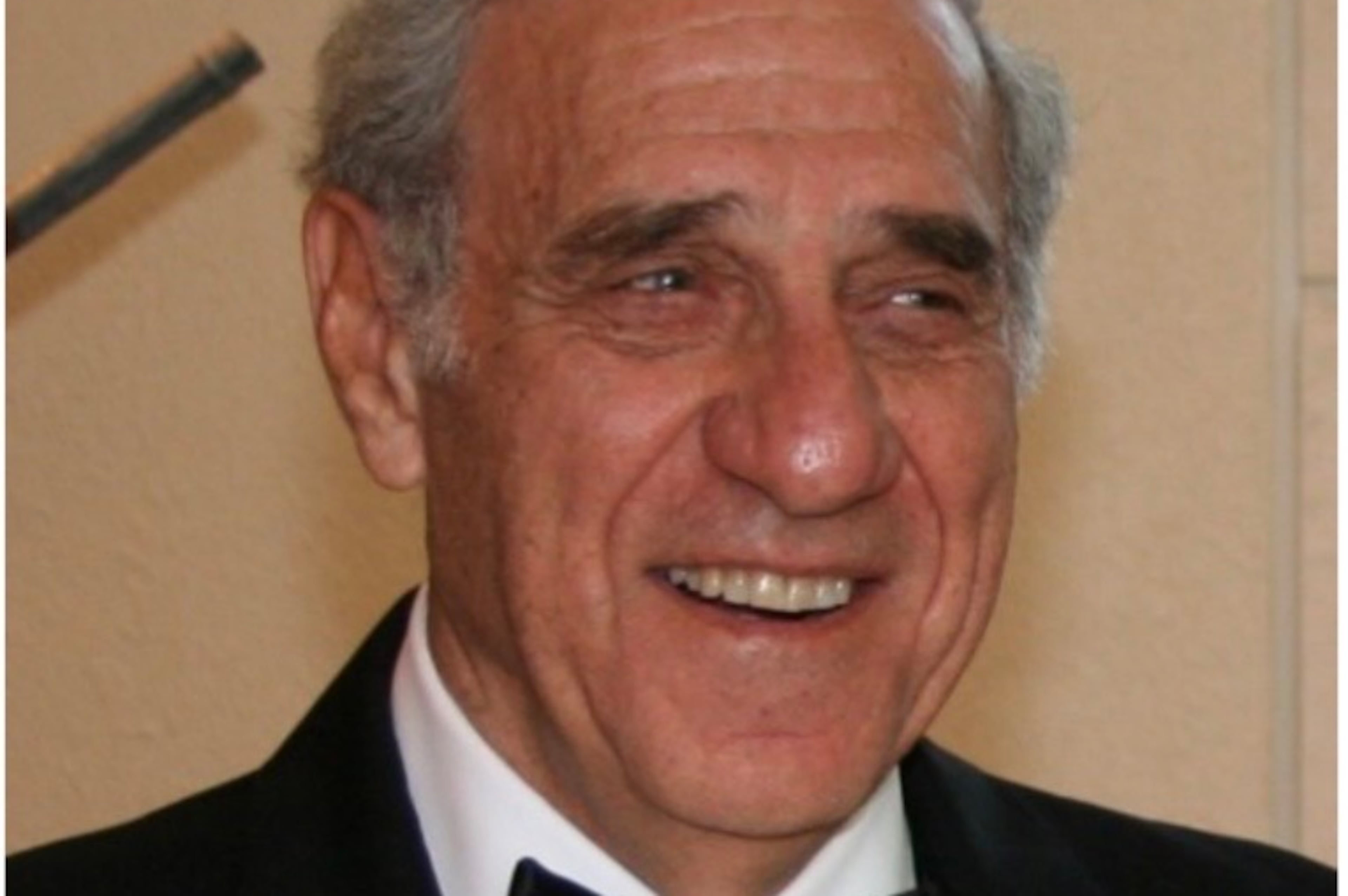

Warren Fortson, 92, paid a price for supporting integration

In 1959, 31-year-old Warren Fortson moved to Americus, Ga., and within a few years became attorney for Sumter County and the county school board, as well as president of the Sunday school at Americus’ First Methodist Church. His private law practice included criminal, real estate and corporate cases.

His life carried a shimmering veneer of small-town mid-century Southern propriety. He and his wife Betty had five children and lived in a circa-1900 18-room mansion. She served on the garden club, the Junior League and was soloist in the First Methodist choir.

But six years later with racial tensions unfurling nationwide, the Fortsons found themselves in the eye of a media hurricane. Beginning in the early 1960s, he attempted orchestrating a series of mild integrations of various city and county institutions.

An initial grudging tolerance from town folk gave way to intolerance, which would sweep the Fortsons out of town.

Fortson sent his family packing to Atlanta and soon followed. In conversation several years later with Marshall Frady, then writing for Atlanta Magazine, Fortson wrestled with bouts of cynicism regarding the civil rights movement’s effectiveness and worried if his post-Americus life would prove “anticlimactic.”

But he wound up practicing law an astonishing 63 years — a dazzling courtroom litigator who didn’t retire until 2017. Along the way he counseled not only his clients but a litany of young lawyers seeking erudition from the silver-tongued maestro.

Warren Candler Fortson Sr. died of congestive heart failure in his Atlanta home on August 1, two weeks before his 92nd birthday. He was cremated and will be buried alongside generations of Fortsons at the family’s ancestral church, Pope’s Chapel Methodist, outside Tignall in East Georgia.

“He was my co-counsel and coach,” said the former U.S. Senator Wyche Fowler who worked in the same law firm from 1970-77. “He taught me how to try cases effectively, how to prepare questions and anticipate objections. He had an enduring sympathy for the underdog. That was definitely a theme throughout his life.”

Deep Georgia roots

Fortson was the youngest of eight children born in Washington, Ga., to lawyer and school superintendent Benjamin Wynn Fortson and Lillie Wellborn Fortson on August 14, 1928.

He came from a family as embedded in Georgia as the red clay. His oldest brother Ben, Warren’s senior by 24 years, was Georgia’s secretary of state for 33 years. His grandfather, Charles John Fortson was a college roommate and best friends with Warren Candler, who was brother to Coca-Cola founder Asa Candler and later a bishop of the Methodist Church and the first chancellor of Emory University.

Fortson moved to Americus several years after graduating from Emory Law School. There, he became close with a peanut farmer and school board member from nearby Plains named Jimmy Carter. In 1962, Carter lost his first run for for a state senate seat because of ballot-stuffing by a local political boss. Fortson and an Atlanta lawyer named Charles Kirbo challenged the election, getting it overturned in Carter’s favor.

Carter wrote in his 1992 book “Turning Point,” that the final verdict was handed down by a Judge Crow, and that night he and Fortson drank “a lot of Old Crow” [bourbon] in the judge’s honor. According to Jane Fortson Eisenach, from then on her father sent Carter a bottle of Old Crow after every election victory, including the one for the White House.

President Jimmy Carter wrote in a statement to The Atlanta Journal-Constitution: “Rosalynn and I are saddened at the passing of our friend Warren Fortson. Warren was a superb South Georgia lawyer who helped me fight election fraud to win my seat in the Georgia State Senate in 1962. …Warren was a brave advocate for racial equality in a time and place where it was a costly position to take, but he never backed down. We are grateful for his service to our community and thankful for his friendship, and we send our condolences to his family.”

Fortson early efforts in Americus convinced school board members to desegregate Americus High School with a token four students. He began accepting Black clients in his practice and helped integrate the town’s largest manufacturer, Manhattan Shirt Company.

The critical peak arrived in the summer of 1965 after the drive-by killing of a young white man who’d been protesting the jailing four Black women arrested at a polling location. Trying to avoid further violence, Fortson delved into establishing a biracial commission. The white community responded with a petition signed by 2,000 demanding his dismissal as county attorney.

He was pelted with threats over the telephone and sometimes, to avoid the incessant ringing, he’d hole up with out-of-town reporters at a local hotel. Clients stopped showing up at his office and then stopped paying him. Friends would cross the street to avoid conversation.

His oldest child Jane Fortson Eisenach was 12 in 1965 and remembers seeing her 9-old brother, Warren Jr., attacked by older boys on the playground.

“They were going after him with a baseball bat,” she said recently. “I jumped in the middle of it with the native belief that boys wouldn’t hit girls. But when I tried to intervene, they turned on me.”

Black civil rights workers, including John Lewis, showed up outside Fortson’s church, from which Blacks had been barred. Church leadership told Fortson he was no longer welcome, inspiring the pro-integration Atlanta Constitution columnist Ralph McGill to write, “Well, the Devil has just made Jesus look bad in Americus.”

It was a particularly soul-wrenching moment for Fortson. His daughter Susan Eginton was almost six the day the family walked out of First Methodist for good. In a recent email she wrote, “We were all climbing into the car to leave when Daddy looked back at the church and said, ‘God welcomes all of His children in His house.’ I will never forget those words.”

They soon left Americus as well.

With his family settled in an Atlanta apartment, Fortson was appointed as the only Southern lawyer on the national Lawyers Committee for Civil Rights Under Law. Living during the week in a Jackson, Miss., apartment, he defended Black clients in courts throughout that state. His marriage, however, gradually fell apart in late 1960s, and Fortson moved to New Orleans to practice maritime law while going through a brief second marriage.

He returned to Atlanta in 1970, initially working for a large firm then breaking away to form his own. He served as general counsel for Atlanta Public Schools from 1972-93 and later as council to the president of Georgia Perimeter College.

He’d been single for 17 years when he took Linda Lanier out on a Tuesday night date in 1987 and two days later suggested they should get married. He was 59 and she was 37. “It was such a love match,” said oldest daughter Jane Eisenach. “He had been alone for so long, and she has been so remarkable.”

When their daughter Savannah was born in 1989 and friends complimented him on his “cute granddaughter,” he’d snap back, “Granddaughter, hell! She’s mine!”

Fortson’s final dozen years were spent in private practice and collaboration with Linda Lanier Fortson. Mostly they focused on representing educators, included 44 teachers involved in the Atlanta Public Schools cheating scandal.

“He saw teaching as one of life’s noblest callings,” Linda Fortson said. “He understood they had very difficult work conditions, that they were vulnerable, that they didn’t have money and that they needed legal help.”

It was Linda who finally convinced Warren to retire. Years earlier, before their marriage, he’d had a heart attack and quadruple bypass and was now on his fifth pacemaker. But he’d become remarkably healthy, never using a cane or walker, exercising five days a week and streamlining his diet which no longer included indulgences like Old Crow bourbon.

“He did miss working,” she said. “He had a puritanical view. He felt like he needed to produce something. I told him he’d produced enough, that it was time to become a hedonist.”

Warren Fortson is survived by his wife Linda Lanier Fortson and his seven children, Jane Fortson Eisenach (Jeff) of Oakton, Va., Warren Candler Fortson Jr. (Vickie) of Lawrenceville, Margaret Leslie (George) of Ball Ground, Susan Eginton (Mark) of Ithaca, N.Y., Lyda Kathryn Fortson of Roswell, Dr. Benjamin Fortson (Kelly) of Ann Arbor, Mi. and Savannah Lanier Fortson of Atlanta, along with six grandchildren and two great grandchildren.