The class was PSC 253 -Scope and Methods of Political Science.

The idea of taking the required course made more than a few Morehouse men break into a nervous sweat.

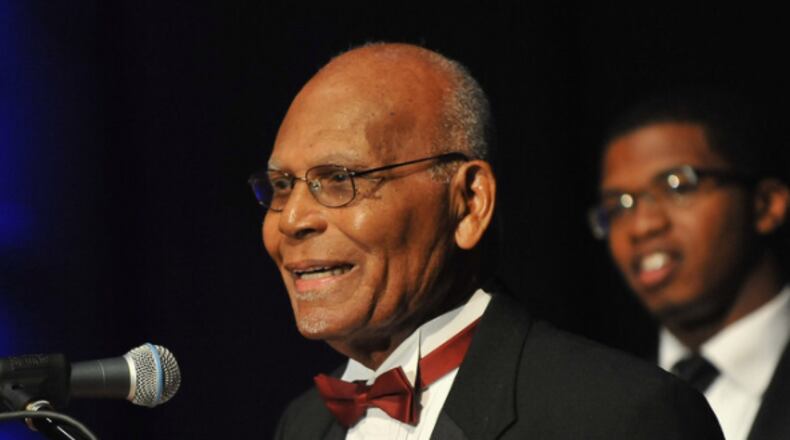

Tobe Johnson — a Morehouse fixture and influential intellectual — taught it as political science professor and department chair. It was a mandated a deep dive into everything from the very definition of the discipline to policy analysis, along with a heavy dose of research.

“It had the reputation of being a difficult class because, unlike other political science courses, you just didn’t come and talk about politics,” said Matthew Platt, a one-time student and now the academic program director for political science on the Atlanta campus.

Johnson was a tough taskmaster, said Platt, but he quickly added that Johnson also helped any undergraduate arriving at his office with a question or need for advice.

“There was a strong element of lifting people up,” Platt said. Johnson hired students who did well in his courses as teaching assistants, paying them out of his own pocket. He also helped many progress to graduate and law school.

He helped lay a foundation of Black leadership in Atlanta and elsewhere as his mentorship led to scores of Morehouse graduates becoming influential attorneys, judges, diplomats, public office holders and professors.

Black politicos flocked to him for advice, including former student Maynard Jackson when Jackson successfully sought office as Atlanta’s first black mayor in 1973.

“My dad said, ‘Not everybody can be out marching. Somebody has to be at the table when opportunity comes, ‘” said Cheryl Johnson.

Tobe Johnson, 91, died May 7 after battling cancer. He is survived by his wife of 61 years Goldie, daughter Cheryl and son Tobe Johnson III, grandchildren Naim Johnson-Rabbani and John Johnson and a number of nieces and nephews. A private 11 a.m. May 21 celebration of his life is set at Morehouse.

The Pratt City, Alabama, native arrived at Morehouse in the late 1940s, just months after his father had died. Legendary school president Benjamin Mays and others took the 15-year-old under their wings, nurturing his interest in social justice, the nascent civil rights movement and the political process.

That push for equality showed up in a quiet but but dramatic turn later for Johnson. He took a bus from New York to visit a friend in Selma, Alabama, in the 1950s, his daughter said. As the bus crossed the Mason-Dixon Line, black passengers moved to the back. Johnson stayed put all the way to Alabama.

“When he got there, his friend’s mother was like ‘Are you crazy?’” Cheryl Johnson said. His response? “They didn’t ask me and I wasn’t going to volunteer.”

Graduating in 1954, Johnson headed north, becoming the first person of color to earn a Ph.D. from Columbia University. A teaching position at a Texas HBCU drew him west.

Two years later, Mays recruited him back to Morehouse to help build the political science department.

He established the Morehouse urban studies program and helped found Black studies programs elsewhere. He shepherded a groundbreaking Peace Corps training program.

And when he spoke, people listened.

Morehouse’s Martin Luther King Jr. Chapel founder and dean Lawrence Carter saw that ability to command attention.

“I had the chance to observe him most often in faculty meetings, and I soon came to realize that he was the dominant voice there. For 41 years, he asked the most serious and tough questions and gave the most in-depth critiques of what was going on and what would work and not work. "

Longtime friend Marcia Klenbort credits Johnson with helping weave other changes into Atlanta’s political-racial fabric, as he aided the 1970s-era redrawing of the city charter. He helped do away with citywide votes for then-alderman, which had effectively prevented Blacks from taking office. He lent support to a group of Black and white women that included his wife, which started a cooperative interracial preschool in 1965 — a radical idea for its time.

“He was very interested in understanding how the political system worked,” she said, “changing it, but also understanding its workings.”

That sense of knowing political workings also led him to leadership roles with MARTA, Leadership Atlanta and the Atlanta Regional Commission.

Johnson, said his daughter, operated from an abiding faith that “that the city of Atlanta could be a great place with opportunity for everyone.”

Follow the AJC obituaries page on Facebook for Atlanta, Georgia obituaries, condolences, and death notices from the Atlanta Journal-Constitution

About the Author

The Latest

Featured