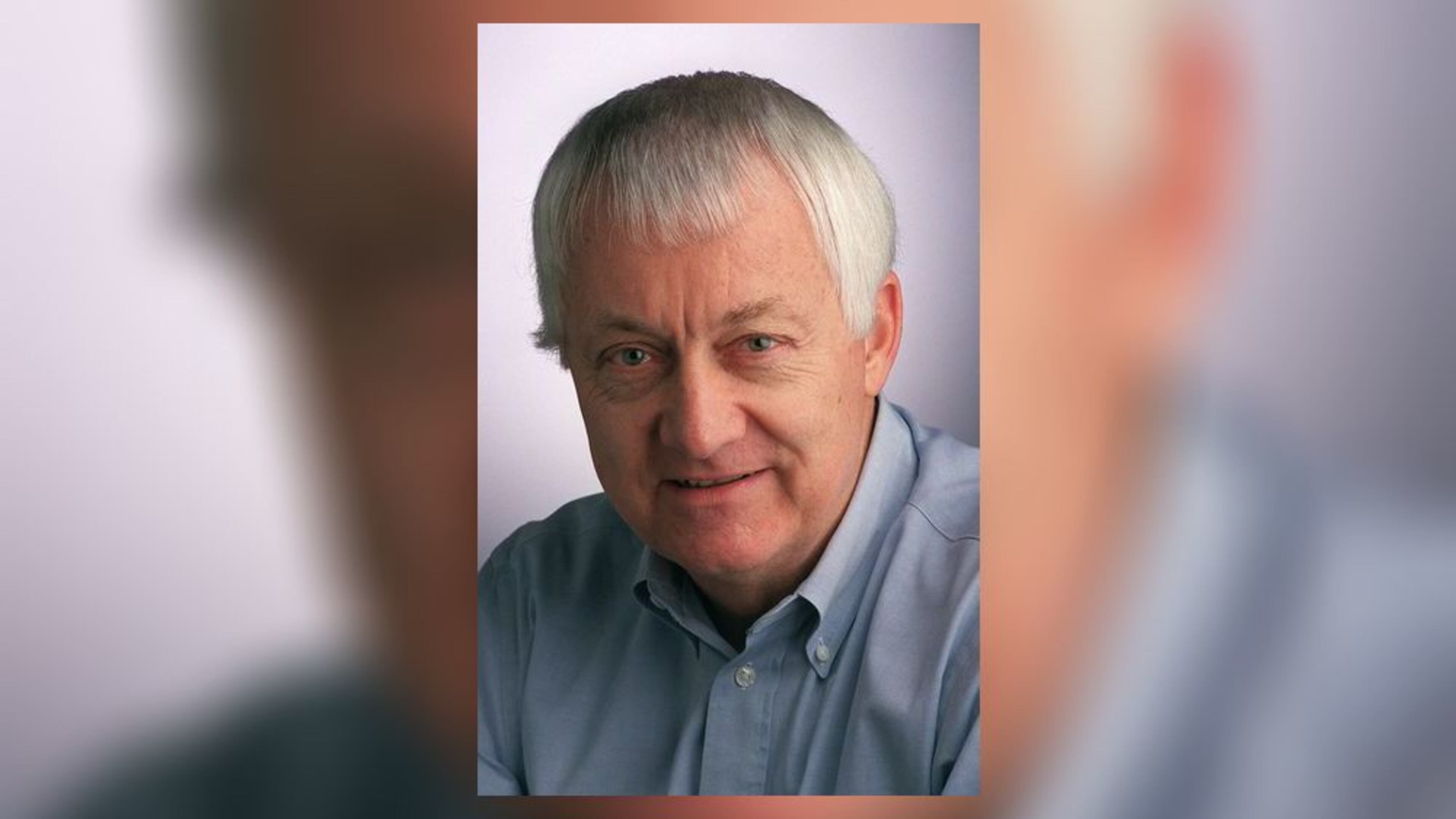

Remembering Herb Steely, the soul of The Atlanta Journal

Reporters loved Herb Steely. Except, perhaps, between the hours of 5 a.m. and 7 a.m.

For decades, Steely practically was The Atlanta Journal. As the morning city editor, he was relentless in his pursuit of news for Atlanta’s afternoon newspaper. That often meant rousing reporters before sunrise to cover a breaking story. With deadlines fast approaching, it was time to get moving.

“I can’t tell you how many times I heard him wake up a reporter — at 7 a.m., shoot, even 5 a.m. — when there was breaking news on their beat,” recalled former morning reporter Mike Morris, Steely’s right hand man for more than 20 years. “And he’d always ask, ‘Are you going to sleep all day, Bud?’” (Or “Kid.” He always addressed male colleagues as “Bud” and female colleagues as “Kid.”)

After being jarred from sleep, the unfortunate Bud or Kid would crawl out of bed, find coffee and start moving heaven and earth to deliver the news for Steely. No one wanted to let him down. And in truth, if a reporter ever needed help in not letting Steely down, he was happy to provide it, pressing and pushing and reminding the reporter of that looming deadline.

Herbert Arthur Steely, the former city news editor for The Journal and The Atlanta Journal-Constitution, died Tuesday of Parkinson’s disease. He was 82.

Back in the day, putting out an afternoon paper was a frenetic, exhausting exercise in meeting one deadline after another — with bursts of news akin to today’s Twitter feeds. Reporters and editors often started working on the next edition’s stories even before the last edition’s deadline had passed. The Journal newsroom could be a place of foul language and the occasional flying projectile as deadlines approached and tempers flared. But Steely, for whom the deadline pressure could be most intense, kept his temper in check and usually managed a smile for his Buds and Kids.

“He was the soul of The Journal and he was the conscience of it, too,” said Morris, who felt Steely was like a second father to him.

It’s hard to overstate Steely’s commitment to the readers of The Journal – or to the reporters who met (and occasionally missed) its killer deadlines.

“He called me many times over the years early in the morning and his voice was always exactly the same,” former reporter Patti Ghezzi said. She recited his typical greeting: “Hey, Kid, we’ve got something going on.”

She added, “He really was just the greatest, and no matter how early he called it was impossible to be mad or even annoyed.”

Steely began his career at The Atlanta Journal in January 1966 when it and The Atlanta Constitution, the morning paper, had separate staffs. The competition was fierce and Steely relished, as he would say, “beating the Consti” (CON-STYE) on a big story.

When the news staffs merged, the main competitors were all the other news organizations in town. Big, fast-breaking news and scoops exhilarated Steely, who meticulously fact-checked stories even when on a crushing deadline.

“He loved the newspaper deeply,” said former reporter Charles Seabrook, who now writes the paper’s “Wild Georgia” column. “It wasn’t just a job to him. He lived it and breathed it. He would tell reporters to ‘get it right, get it first and make it read good.’”

In October 2001, a long-anticipated decision was made to cease afternoon publication of The Journal and absorb it into what is now: The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. Even though he knew it would happen someday, Steely broke down and wept when told the news.

The Journal’s longtime motto on its masthead was “Covers Dixie Like The Dew.” For its final edition, on Nov. 2, 2001, Steely helped arrange for it to be in past tense: “Covered Dixie Like The Dew.”

Steely, who retired in May 2003, had a mischievous side. A few days before every Thanksgiving, he’d post signs on the newsroom’s walls that said the paper was giving out free turkeys at the loading dock. (It wasn’t.)

The ruse often duped young reporters, even some naïve veterans, getting them to traverse the labyrinthian production building out back for what they thought would be a free bird. One year, former AJC photographer Pouya Dianat fell for the turkey scam. Naturally, his fellow photographers watched with glee (and even took pictures) from windows above as he wandered around the loading dock.

Steely was fanatical about his alma mater’s basketball team, the Kentucky Wildcats. During games, he’d sit with his eyes glued to the TV — at least for as long as he could stand it. When the scores of some big games got too tight, he’d have to walk outside and peek through a window to see the score.

A native of Williamsburg, Kentucky, Steely served two years in the Army after graduating from the University of Kentucky. He was stationed at Ft. Smith, Arkansas, where he later got a job at a local newspaper. He also worked at the Savannah Morning News before joining The Journal.

Shortly after moving to Atlanta, Steely met his future wife Allison on a blind date. They were married for more than 50 years.

Allison said she was attracted to him because they shared the same values and “because he always said what he thought. What you saw with Herb was what you got.”

Survivors include his son Brian and daughter-in-law Sarah; daughter Lauren Gragg and son-in-law Lee; brother Allan and sister-in-law Barbara; and three grandchildren. Due to the coronavirus pandemic, a memorial service will be scheduled at a later date.

Former AJC staff writer Don O’Briant contributed to this story.