As a broadcast and print journalist, Maynard Eaton uncovered and told unforgettable stories about both famous and forgotten people, winning awards for his work. During a varied career, he ran political campaigns, hosted talk shows and pushed for advancing civil rights. He served as spokesman for the SCLC, as the president of the Atlanta Chapter of the National Association of Black Journalists, and he taught journalism students at Clark Atlanta and Hampton universities, serving as a mentor to many.

He had handled so many professional challenges over the years, Eaton thought he could overcome one more. After a March 15 diagnosis of lung cancer, he planned to take chemotherapy, get better and return to Hampton University to teach this fall. But he couldn’t pull off this final assignment. He died Tuesday night at the age of 73.

“We never thought he would be alive only for a couple of months,” said Robin Eaton, Maynard’s wife.

Maynard Eaton was reared in Orange, New Jersey. He was the son of Johnsie Leake Eaton and Jack Eaton. His mother was a staunch Democrat and an independent pastry chef, and his father was a union truck driver. Maynard delivered newspapers, and his father drove him on his Sunday route, “provided that Maynard read the paper to him and knew what was in it,” Robin Eaton said. “That started his love of storytelling and journalism.”

Maynard Eaton graduated from Hampton Institute in 1971, now Hampton University, where he co-captained the baseball team. He earned a master’s in journalism from Columbia University and took a job at WVEC-TV in Hampton, Virginia, as the station’s first African American reporter. While working at WPLG-TV in Miami he was sent to cover an independence celebration in the Bahamas. The stadium announcer was reading the names of celebrities at the event. When he announced, “Maynard Eaton!” the audience roared. “Who the heck are you?” a nearby radio announcer asked Eaton. The Bahamas received Eaton’s Miami station broadcast, and he was the first male Black reporter Bahamians had seen.

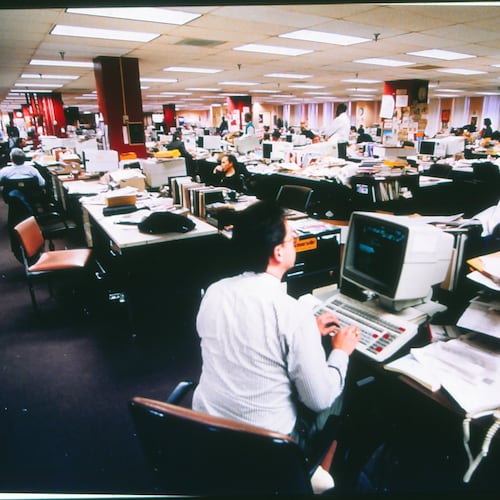

Eaton came to Atlanta to work at WXIA-TV, Channel 11, in 1978, where he covered city politics, the Capitol and other subjects. There, said his former colleague Evelyn Mims, “Maynard was … very passionate in his storytelling. His words came alive, he went deep. He was a deep thinker about everything.”

During his career, he received eight Emmy Awards for television news reporting. He was honored for his political commentary for WTLK-TV and WATL-TV in Atlanta; for his work as a reporter for World News Monitor; as southeast field producer for USA Today and BET television; and as a writer for Ebony Journal and Prime Time, two locally produced television magazine shows.

Tom Houck, a civil rights activist and journalist, met Eaton on his first day on the WXIA job and watched his multi-faceted career unfold in Atlanta. Always, Houck said, “Maynard was a joyous person. He really wanted the struggle for civil rights to move forward.”

“Maynard reported on me and so many others in the movement,” said former SCLC Chairman Bernard Lafayette. “He made sure that not only were my words being communicated but our mission in the movement and the reasons for those words and mission were communicated.”

Taking a break from journalism, Eaton helped run political campaigns, and he served as spokesperson for the SCLC.

Stan Washington, the editor of The Atlanta Voice, hired Eaton as a freelancer to write a weekly column, “Politics 411.” Washington said Eaton had great skills as an interviewer and had the kind of charisma that made people want to share information, knowing Eaton would be discreet. “He loved covering politics, loved finding out how the mechanism worked,” Washington said. “He had so much insider information because he took the time to cultivate relationships.”

The Atlanta City Council issued a statement saying that “Maynard Eaton was instrumental in shaping journalism and the communications field, particularly in Georgia politics. He worked to ensure that the experiences and perspectives of Black communities were heard.”

Robin Eaton said, “I think his most enduring legacy is the students and young people who were influenced by him. He opened those doors and laid a foundation for other Black journalists. And he was so excited to be at Hampton, helping the next generation.”

In addition to his wife, Eaton is survived by his sister Melba Eaton, his children Michelle Eaton-Dixon, Nicole Eaton, Mya Eaton-Fuller, Maynard Eaton, Jr., and his stepdaughter Colette Hill, as well as grandchildren, great grandchildren and a nephew. There will be a memorial services in Indiana, Hampton and in Atlanta at Ebenezer Baptist Church on June 16 at 11 a.m.

About the Author

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured