Korean War hero Col. Ben Malcom dies at 94

It was Ben Malcom’s casual low-key tone paired with a Korean War narrative seemingly ripped from the pages of the Rambo novels that struck Ron Martz.

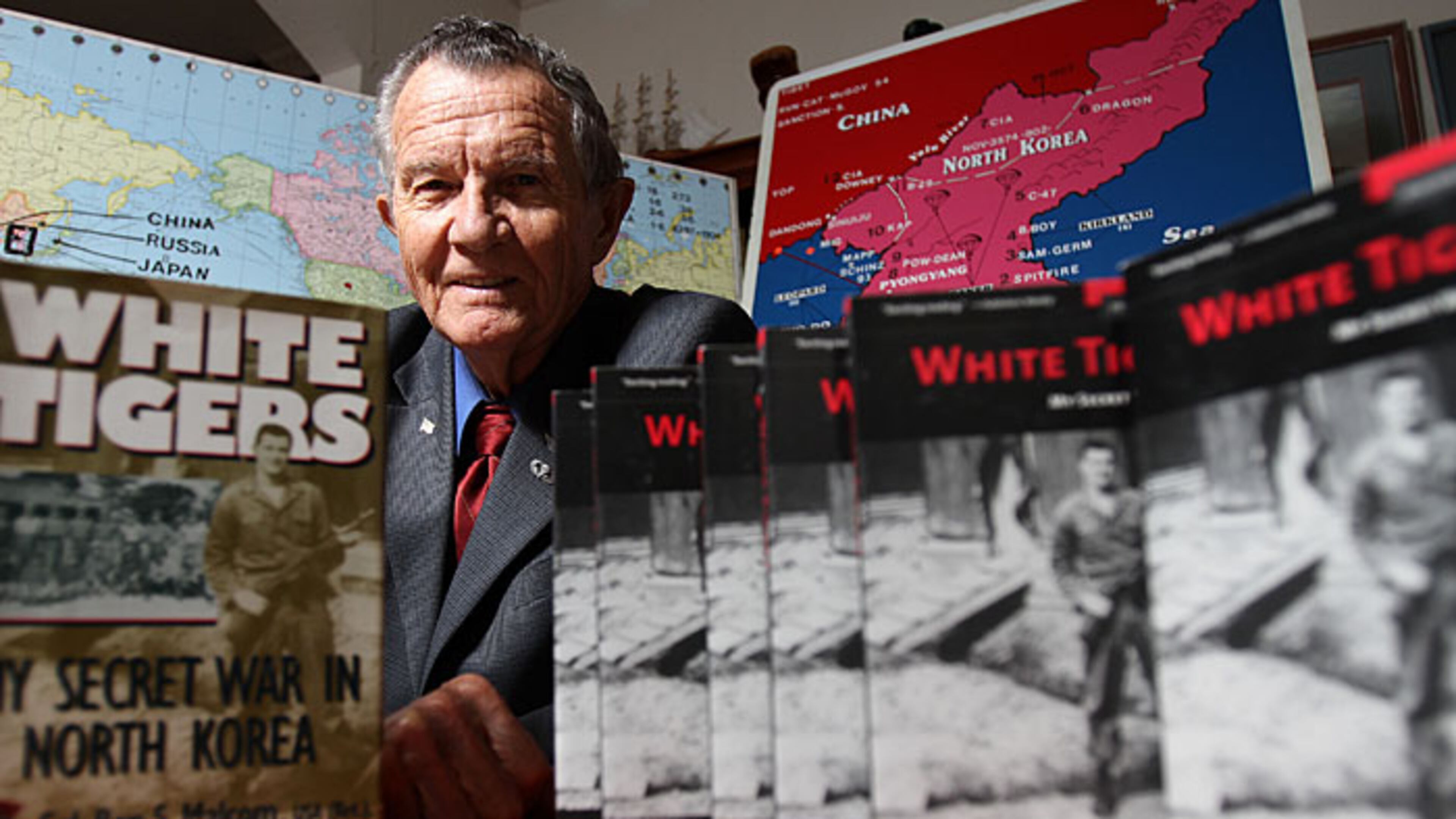

The veteran Atlanta journalist had sat down to quiz the then-retired U.S. Army colonel for what became the 1990s book “White Tigers: My Secret War in North Korea.”

Malcom described how he’d led a group of North Korean defectors in a series of guerilla operations after training them at a clandestine island base 125 miles behind enemy lines. From that redoubt, they staged risky forays onto the mainland.

The so-called “Donkey Units” blew up rail lines and North Korean military ordnance, robbed banks and pulled off currency-destabilizing counterfeiting operations.

Martz says Malcom also disclosed sometime after the book came out they had engaged in assassinations, while insisting he was not personally involved. He’d feared the disclosure might cause repercussions for any of the brotherhood still living.

“He was just so matter of fact describing these incredibly dangerous missions, “recalled Martz, a retired Atlanta Journal-Constitution reporter and editor.

He was modest to a fault, said colleagues.

“He didn’t strut about proclaiming, ‘Look at me. I’m so great,’” said Jim Minter, another retired journalist who went to military school (formerly North Georgia College, now folded into the University of North Georgia in Dahlonega) with Malcom in the late 1940s.

He remembers Malcom, just a year off his parents’ impoverished farm in Monroe, Georgia, as “tall, lean and crisp in starched khakis.” He was a “can do” leader, unafraid to take the initiative.

One example: Malcom’s son Ben recalled the story of a flag getting hopelessly stuck atop a towering flagpole at the school. Malcom approached a commander and proclaimed that he could bring it to earth.

“Without hesitation, he removed his shoes and socks, ascended the pole and successfully retrieved the flag,” Ben Malcom said.

Retired Army Col. Ben Malcom, 94, died in his sleep Oct. 30, from complications of old age. A celebration of life is set for Dec. 20, which would have been his next birthday.

Malcom’s military career spanned more than a generation, from 1950 to 1979, and included service in staff and combat roles, including wartime tours in Korea and later, Vietnam, where he piloted helicopters.

And he broke new ground. Col. Joe Matthews, commander of the military program at North Georgia, said Malcom is considered one of the founding members of the modern special forces.

His accomplishments and a string of awards and accolades aside, it was his off-the-books service in North Korea, declassified in 1990, that drew the most rapt attention when he spoke to audiences ranging from graduating special forces troops at Fort Bragg in North Carolina to community groups, Martz said. The guerilla war was considered so hush-hush that after a mission to blow up a large, deadly North Korean artillery piece embedded in a mountainside, Malcom was awarded a Silver Star for valor but was unable to acknowledge what he’d done.

“There was some ferocious fighting going on there,” Malcom said in a video interview, describing the bloody fight back to the beach.

The experience of hunting jackrabbits on his parent farm brought his unit to safety in another dicey confrontation. Malcom recalled rabbits plunging into the thickest, thorniest brush around to escape pursuit. That strategy proved essential when he and other partisans headed to a meeting with supposed North Korean friendlies who turned out to be heavily-armed troops.

The younger Malcom quoted his dad: “I was confronted on one side and I looked back and saw there were a bunch of thorns and told my guys just follow me. They quickly — and painfully — left the enemy behind.”

Malcom was more than a battle-tested leader. His knack for cultivating relationships and his consuming curiosity helped win the respect and trust of his troops. In his final assignment commanding Fort McPherson in Atlanta, he collared base personnel daily and had them join him on four-mile to five-mile runs. He could talk to the lowliest soldier on post as if they were an equal partner.

“Everybody that I ever met that worked for them said they would follow him anywhere,” said Ben Malcom.