Credit: AJC

Credit: AJC

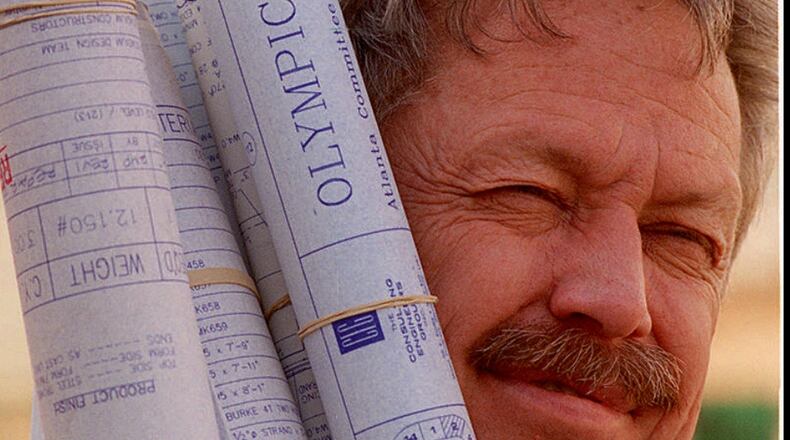

Shaped by a childhood of diversity and perseverance, Atlanta architect George Taft oversaw the creation of some of the city’s most iconic sites, including the Georgia Dome, the 1996 Olympic Stadium (which became Turner Field and is now Center Parc Stadium), and a major expansion of the Georgia World Congress Center.

“George Taft left his mark on Georgia through his work on many notable projects,” said Christy Crisp of the Georgia Historical Society.

“In addition to the Dome, Mr. Taft contributed to … Atlanta’s image as an international city, positioning it to play an important role in global commerce for many years to come.”

Taft died Aug. 22 at Holmes Regional Medical Center in Melbourne, Fla., from complications related to COVID-19, one day away from his 78th birthday. His ashes will be interred in Port Washington, N.Y. Friends plan to hold a memorial service in the future.

He was born George Edwin Taft in 1942, the only child of a toy-seller and homemaker in a working-class neighborhood in New Hyde Park, N.Y. A birth defect left one leg shorter than the other, a matter Taft regarded as no big deal, say those who knew him.

“He was not the fastest kid on the block, but he kept up. He liked everybody. Our neighborhood was a melting pot, but getting along with everyone was not a problem for George,” said Taft’s oldest friend, Pete Rozea. Born nine days apart to mothers who were close friends, Taft and Rozea often shared a crib and remained close for life.

The ability to connect with a diverse group of people and a history of overcoming potential problems prepared Taft for the demanding duties he assumed after graduating from Pratt Institute. He led teams of over 100 engineers, specialty consultants and skilled laborers on some of the largest construction projects in Atlanta history.

“Many of us have a project of a lifetime. George had three,” said Glenn Jardine, an engineer who worked alongside Taft at Atlanta-based Heery International Inc., before it was acquired by CBRE Group Inc. in 2017.

“You’d never wear down George Taft. He was unflappable,” said Jardine, now the executive managing director of CBRE Heery, stressing Taft’s brilliance in implementation, management and planning.

“He had the uncanny ability to identify issues before they became obstacles.”

Taft presided over projects exceeding $1 billion in a 15-year span, beginning in 1989 with construction of the Georgia Dome. At the time, it was the largest covered stadium in the world and hosted more than 37 million people and 1,400 events before being demolished in 2017.

Taft also directed the 3-year-long construction of Olympic Stadium, the centerpiece of the 1996 Summer Olympics, and then managed its 1997 conversion to Turner Field as home of the Atlanta Braves. His last major project was the Georgia World Congress Center’s Phase IV expansion in 2000, which added 1.1 million square feet, making it one of the largest convention centers in the nation.

Taft was a hands-on project director often found in the middle of construction sites wearing blue jeans and a hard hat, Jardine said.

“He always had a notebook with him, lots of sticky notes — this was before the software we have today, remember.”

Taft’s retirement party from Heery in 2008 turned legendary. While the celebration was underway in Midtown, the Georgia Dome was hit by a tornado, as an SEC Tournament basketball game was being played there. Taft, who referred to his structures as his babies, rushed to see the damage and came out of his short-lived retirement to lead repair efforts.

“It was a strange convergence. Like a message from the universe that he wasn’t finished yet,” said Martha Pacini, Taft’s coworker at Heery for 20 years.

“The projects were his children. They were complicated. They required a lot of nurturing. You could tell by how much care he took.”

Credit: AJC

Credit: AJC

While known for 18-hour workdays, Taft balanced job stress with an active lifestyle and close relationships. Despite an early Vermont skiing accident that worsened his limp, he continued skiing, ice skating, jogging, and sailing. He loved watching the Braves and Falcons. He volunteered at animal shelters, sent birthday and Christmas cards to people for years after working with them, and kept friendships for life.

“He worked on the biggest, most complex projects, but he always remembered the little things. He always made time for people. He was incredibly kind,” Pacini said.

Taft was also known for his infectious laugh and unwavering positive attitude.

“He was a joy to be with. You knew that no matter what kind of day you were having, you were going to feel better when you saw George,” said longtime friend Jeff Reed.

About the Author

The Latest

Featured