By his mid-40s, Charlie Shaffer was already a high achiever: he had been a sports star in high school and college, Phi Beta Kappa member, a partner in the prestigious Atlanta law firm King & Spalding, and he had a happy marriage and family.

So he didn’t really need what Billy Payne was offering in the early 1990s: a chance to work insane hours on a ridiculously improbable effort to woo the 1996 Summer Olympics to Atlanta. Payne had heard about Shaffer’s smarts, connections, and people skills, and asked him to join what became known as the “Atlanta Nine,” the small core team that eventually landed the games.

Shaffer said yes, and changed his future and the city’s.

“He just couldn’t get enough of it,” Payne recalled. “He had a full-time job, and at the same time I was leaning on him pretty heavy to travel here and go there and win this vote. I frankly would go through periods of ‘Man, I’m tired.’ When I felt worn out by the process, I would just pick up the phone and call Charlie. He was always a breath of fresh air.”

Shaffer went on to elevate and inspire Atlanta in other ways: he was president of the Atlanta Sports Council where he brought a Super Bowl and two NCAA Final Fours to the city; he was president and CEO of The Marcus Autism Center for children with developmental disabilities; he raised money and advocated for The Westminster Schools and the Emory Goizueta Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center.

Charles Shaffer Jr. died March 18, 2021, of Alzheimer’s Disease at Mann House, an assisted living Alzheimer’s care facility in Sandy Springs. He was 79.

“His energy and enthusiasm could be exhausting,” said lifelong friend and fellow Atlanta Nine alum Charlie Battle. “He optimized everything about life. I was talking to a friend who said he wasn’t going to ask Charlie for advice any more about where to go to a restaurant or where to go on vacation because everywhere Charlie went was the best thing that had ever happened.”

“That energy he had was never depleted because it was never about him, it was never about his ego,” said his son, Charles III. “His energy was constantly replenished because he was energized by the spirit he got from the people around him.”

Shaffer was born Dec. 21, 1941, in Durham, North Carolina, and was a star high-school quarterback. A knee injury ended his football career, but he became co-captain of the University of North Carolina basketball team during the team’s first three seasons under legendary coach Dean Smith. While in college he met Harriet Houston, and they married in 1964. He graduated from the UNC School of Law in 1967, and the couple moved to Atlanta where he joined the law firm of King & Spalding as a trial lawyer.

Even as the 1996 Olympics were underway, Shaffer became president of the Atlanta Sports Council.

“He was integral in getting Atlanta the Super Bowl for 2000, and the 2002 and 2007 NCAA Men’s Final Four,” said William Pate, president and CEO of the Atlanta Convention and Visitors Bureau. “He wanted to make sure when we welcomed people that the event ran flawlessly, that the city performed with perfection, with the idea that if we did a great job, we could get the event back later.”

After helping Atlanta become a major sports destination and serving as president of the Atlanta Bar Association, Shaffer retired from King & Spalding after 35 years in 2002 to run the non-profit Marcus Autism Center.

“You practice law a long time and maybe you decide you need to go somewhere and make a difference,” said his friend Battle. “Charlie was looking to make a big impact in a different way.”

Home Depot co-founder Bernie Marcus offered him the chance to do that at the autism center.

“Thirty-five years of being a litigator was hard work, but he wanted something where he could nourish himself and give back. It was all about service,” Charles III said.

In 2011, Shaffer was diagnosed with Mild Cognitive Impairment and told it would progress to Alzheimer’s Disease. Instead of hiding the diagnosis for fear of what people would think, he became a public fundraiser and advocate, and he enrolled in clinical trials to contribute to new research.

Allen Levey, his doctor and head of the Emory Goizueta Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center, told the AJC in 2013, “It’s very uncommon for people to be public about their memory problem. What Charlie is doing is amazing.”

“It’s not about me,” Shaffer told the AJC about his public advocacy. “Contribute because you might get it.”

Charles III recalled a lesson his father learned from coach Dean Smith. “Dean had this rule when you scored a basket and you came down the court, you point at the person who passed the ball to you. It was never about you,” he said.

“And his whole life the person he pointed to was his wife,” the son continued. “They had a marriage that was the center of who he was.”

He would call himself lucky to have her in his life until the end, he said.

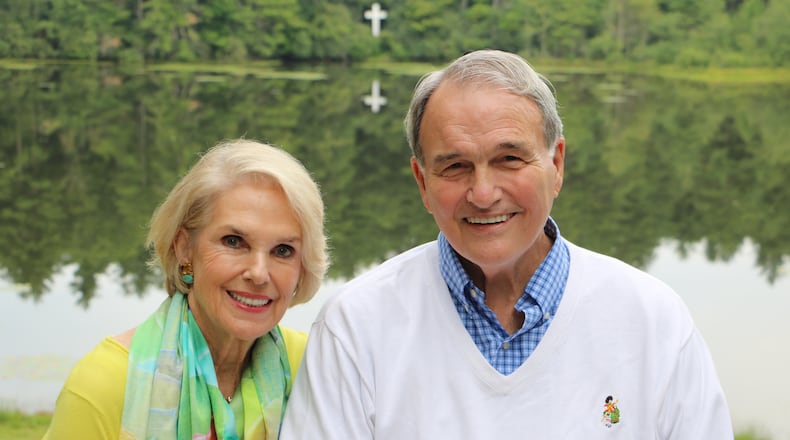

Shaffer is survived by his wife of 56 years, Harriet Houston Shaffer; son Charles M. Shaffer III (Karen) of Greenwich, Connecticut; daughters Caroline Shaffer Vroon (Bryan) and Harriet “Emi” Shaffer Gragnani (Michael) of Atlanta, and nine grandchildren.

The family will have a private burial ceremony in North Carolina, and a celebration of life in Atlanta when conditions permit. In lieu of flowers, donations may be made to: The University of North Carolina’s Charles and Charlotte Shaffer Scholarship Fund; All Saints’ Episcopal Church in Atlanta; Respite Care Atlanta; and the Emory Goizueta Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center.

About the Author

The Latest

Featured