Pain in her arm and lightheadedness sent Doris Jones to the emergency room at Savannah’s Memorial Health University Medical Center. A scan there soon revealed a shock. A filter placed in her bloodstream years before to catch clots had fractured, and debris was migrating toward her heart.

While the main part of the filter was removed, a broken piece is still lodged in the artery that carries blood to her lungs because doctors couldn’t safely get it out.

Others who received the filter, made by Bard, died after it shifted or broke apart. More than 3,000 other patients, including Jones, claim they were harmed by a device that went on the market without first being tested in clinical trials to make sure it was safe and effective.

It didn’t have to be.

Jones’ lawsuit, being heard this week, is the latest of hundreds of thousands involving medical devices blamed for sickening or killing patients, cases that point to a weak federal oversight system for some sensitive devices.

The cases are so many and so routine that federal courts have funneled many into a special multi-district system to consolidate them. Georgia lawyers, plaintiffs, hospitals, courts and medical device manufacturers — the state is now home to scores of them — are in the thick of many of them.

Claims involving Bard filters are consolidated in Arizona. In Atlanta, hundreds of lawsuits are pending, and more are filed every week, involving a hernia mesh implant that patients say dissolved into the flesh it was meant to support. More than 20,000 cases involving transvaginal mesh for supporting pelvic organs, including mesh made at a Georgia plant, are consolidated in West Virginia.

Around the nation, other cases involve metal hip replacements suspected of poisoning patients or a gastrointestinal scope linked to the deaths of dozens infected with antibiotic-resistant bacteria.

In the biggest cases alone, more than 45,000 lawsuits are pending against 13 device makers. That’s not counting 100,000 other suits in those cases that have already been settled, dismissed, or otherwise resolved. And still more come in.

The Food and Drug Administration, which regulates medical devices, clears some sensitive ones for marketing to the public after they've been tested on animals or machines. Then, FDA tracks reports of deaths, injuries and malfunctions afterward.

The government has recognized that the tracking is flawed: Doctors and other healthcare professionals are not required to report anything; hospitals are required to report but sometimes simply don’t; manufacturers decide if a serious injury or death is related to their devices.

To address the issue, FDA last month announced its latest safety plan. To the disappointment of patient advocates, the agency, bound by law to regulate device makers in the “least burdensome” way, still will not require all potentially risky medical devices to first undergo safety testing in humans.

Instead, the plan proposes a shift to mining data from electronic medical records, which FDA says will allow it to more quickly detect risks and safety issues. With that move, the agency hopes to go from only "passive" surveillance through others' reporting problems, to adding "active" surveillance.

Industry groups and the FDA say the system helps ensure patients get life-saving devices. They point out that with hundreds of millions of Americans using more than 190,000 medical devices — counting everything from Band-Aids and Q-Tips to surgical equipment, pacemakers and artificial knees — the number of devices with safety issues is small.

“The system for the most part works fairly well,” Dr. Jeffrey Shuren, director of the FDA’s Center for Radiological Devices and Health, told the Atlanta Journal-Constitution, “but that does not discount the importance about being vigilant about addressing safety issues particularly as technologies continue to evolve.”

Diana Zuckerman, a public health researcher and advocate and president of the National Center for Health Research, is skeptical. “The devil’s always in the details,” she said. “The fact that the FDA is now going to change the process — on the one hand it’s terrible so maybe any change is for the better. But the track record over there is not good.”

Other critics say U.S. law and rules struggle to keep up with a medical device market that has morphed in the space of two generations from tongue depressors, sutures and leg braces to high-tech implants.

They point to a tool called a power morcellator, used in gynecological procedures to grind tissue, that was on the market for two decades before FDA recognized the extent of danger it posed in spreading undiagnosed cancer. The agency took action only after a patient dying from cancer launched a publicity campaign connecting the dots, and The Wall Street Journal wrote about the risk.

Duluth woman awarded millions

The lawsuits against Bard are focusing attention again on the issue of medical device safety and the FDA process for getting devices quickly on the market.

Jones’ case is the second from among the thousands of Bard lawsuits chosen by attorneys and the judge for a “bellwether trial” to test legal arguments and how other cases might play out. The first also involved a Georgia plaintiff, Sherr-Una Booker of Duluth. A jury in March awarded her $3.6 million from Bard, including punitive damages, and $400,000 from a doctor. The case is on appeal.

After Booker got a Bard filter in 2007, she visited hospitals repeatedly for debilitating pain. Finally one day in 2010 a doctor at Gwinnett Medical Center showed her scans with a white shape like a needle over part of her chest. “Is that my heart?” she asked.

It was. She had open heart surgery to remove the filter pieces, but one could not safely be removed and remains lodged in her blood vessel. She will have to have scans the rest of her life to see if it has moved.

She says it’s not about the money. “Ten million dollars wouldn’t have been enough, $20 million wouldn’t have been enough for what they took,” Booker says.

The federal process that allowed the filter to avoid testing for safety in humans prior to going to market is called 510 (k) “clearance.” The mesh, metal hip implants, gastrointestinal scope and power morcellators that are the subjects of lawsuits also were fast-tracked through the clearance process, rather than going through the more rigorous “approval” process.

The FDA offers clearance on devices it deems substantially equivalent to other devices already on the market. Bard showed its filters were substantially equivalent to others it made and received clearance for six over a decade starting in 2002 and 2003.

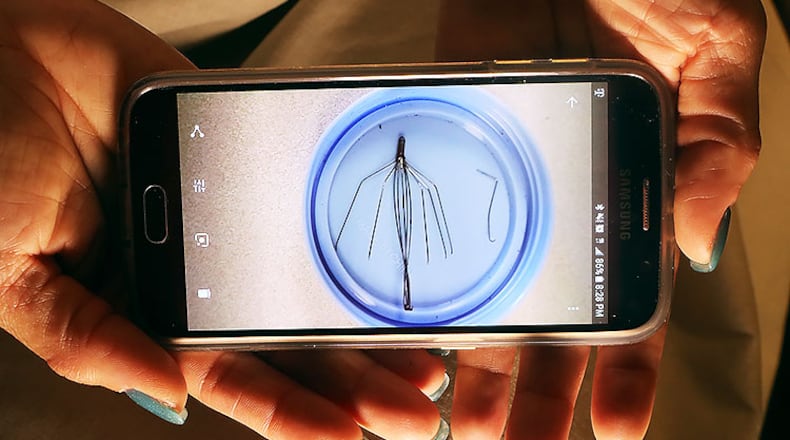

The first retrievable filter, the Recovery, was shaped differently than others already in use, though it was declared substantially equivalent. Bard did a clinical trial that demonstrated it could be safely retrieved, but that didn’t show the device itself was safe.

Not long after the Recovery hit the market, two people died after the filter shifted in their bodies. Bard also learned of other problems, including the filter breaking apart.

That prompted Bard’s lawyers to commission an internal report. It suggested the filter was more dangerous than most and more study was “urgently warranted.”

As problems piled up, Bard modified the filter, introducing new versions but not recalling the device. Bard says it shared all its data with the FDA, which never suggested a recall, and that the new versions were a natural evolution of the product. For its latest filter version, Bard did a clinical trial for safety.

Atlanta lawyer Richard North, who represents Bard in the federal lawsuits, and company officials say that Bard fully abides by FDA rules and went beyond what is required for most devices, doing copious research to ensure its filters worked well. The company says it informs doctors of the risks, and for some patients who can’t take medication to stop clots, its lifesaving potential is worth it.

"Doctors weigh the risks and benefits with these filters, because they treat a potentially deadly disease, pulmonary embolism," North said, emphasizing that all companies' filters are known to have risks.

A spokesman for Bard, Troy Kirkpatrick, stressed the variety of tests the company had done on the filters and continues to do, and echoed that the filters helped tens of thousands of patients over a decade.

“While we understand that some patients required additional interventions or treatment some years after implantation of a filter, it is important to note that the filter helped to protect them from the life-threatening blood clots from which they suffered, and which typically could not be treated with medication,” Kirkpatrick said in a statement.

Speed vs. safety?

The clearance process is only available for devices deemed moderate-to-high risk, or Class II.

Asked why filters which are implanted in a vessel that leads to the heart would not always be in the highest risk class, Stephen Amato, a former medical device executive and now professor and head of regulatory services at Northeastern University, chuckled. “I was wondering that myself,” he said.

Device manufacturers say they submit rigorous new research, sometimes thousands of pages, to the FDA for clearance.

The FDA said in a statement that it determined that the research and user instructions required “would be sufficient to provide a reasonable assurance of safety and effectiveness.”

But the research has limits, and the U.S. Supreme Court has written that the type of federal clearance given to the filter, mesh implants and other medical devices is not in itself evidence of safety or effectiveness.

The medical device industry, led by the advocacy group AdvaMed, lauds the 510(k) process, saying it has “a remarkable thirty year track record of protecting the public health while making safe and effective products available without unnecessary delays.”

The flexibility it provides allows the companies to innovate, the group says; indeed, if anything the FDA needs to approve devices faster.

‘An honor system’

However, beset by critics of the clearance process, the FDA in 2011 asked the Institute of Medicine of the National Academy of Sciences for a study. It concluded the process isn’t intended to evaluate safety and effectiveness and should be replaced.

Several plaintiff’s lawyers told the AJC that although they make a living from its failures, it should be scrapped.

“Put me out of business for the right reason,” said Julia Reed Zaic, one of Jones’ lawyers. The current regulatory system, she said, is “an honor system.”

"I think it's a tragedy and a travesty that frequently these things get off the market because first people get hurt and then lawyers pursue cases," echoed Henry Garrard, a lawyer in Athens.

Garrard is co-lead coordinating counsel on seven groups of cases concerning a vaginal mesh that patients have alleged disintegrated in their bodies, poked through tissue walls and caused them harm. The trials are spanning years. One defendant is Bard, which manufactures meshes at a plant in Covington. Another is Ethicon, which also made a hernia mesh being defended in lawsuits here in Atlanta that are headed to trial perhaps next year. Ethicon has a plant in Cornelia.

A spokeswoman for Ethicon said in a statement that safety is its top priority, it abides by FDA rules and meshes have helped millions of patients.

FDA says it is protecting the public, inspecting makers, offering guidance and recalling products. So far this year, FDA has announced nine device recalls.

FDA had warned Bard that the company had misreported some serious injuries and a death as malfunctions. FDA also noted that it has issued several other alerts regarding filters.

Booker, though, believes the system failed, partly because all those times she went to the hospital her doctors didn’t know what to look for. She argued that the company was interested in making money and that informing doctors about the full extent of danger would have cut into its profits.

The consequences remain. “Whenever I do have the chance of going on vacation or spending time with friends or family I always know where the nearest hospital is,” she said.

» Read the AJC's award-winning investigation, Doctors & Sex Abuse: AJC 50-state investigation

Medical Technology: Deep Georgia Ties

- Georgia is home to scores of medical device companies, including some of the biggest and oldest. The majority of the world's sutures are made at the Cornelia plant of Johnson & Johnson subsidiary Ethicon. The industry estimates it contributes $3.1 billion to the state's economy. The Southeastern Medical Device Association is headquartered in Roswell.

- The state's biotech ambitions extend to startups, too. U.S. News and World Report ranks Georgia Tech's biomedical engineering graduate program No. 2 in the country. Tech in 2012 helped establish the multimillion-dollar Global Center for Medical Innovation, a nonprofit facility in Atlanta that helps develop medical devices and guides companies through processes like 510 (k) clearance, to get them to market.

- The industry is known for its savvy advocacy. Georgia has one congressman on the House Energy and Commerce Committee's Health Subcommittee, Rep. Buddy Carter. His biggest political donor, Brasseler USA, is a dental and medical device company in Savannah.

- On the flip side, the lawsuits alleging patients were injured or killed tend to have prominent Georgia players. Lawyers leading national litigation over medical devices work in Atlanta and Athens, as do lawyers for companies such as the device maker Bard. The federal court in Atlanta is currently hosting a massive set of lawsuits concerning mesh implants and another concerning hip implants. Of five "bellwether plaintiffs" picked to test the Bard filter cases in Arizona, two are from Georgia.

- The companies being sued often have Georgia ties. C.R. Bard, recently acquired by Becton Dickinson, is facing thousands of lawsuits in West Virginia over a surgical mesh made at its plant in Covington. Ethicon, facing thousands of lawsuits in Atlanta over surgical mesh implants, has plants in Athens and Cornelia that make other devices. Stryker, whose metal-on-metal hip implants were tied to cases of metal poisoning, also manufactures cranial and facial implants at a plant in Newnan.

- Devices made in Georgia include high-tech cancer probes, needles, surgical instruments, radioactive "seed" implants to treat cancer, catheters and sutures; varied devices are also made at contract medical manufacturers.

About the Author

The Latest

Featured