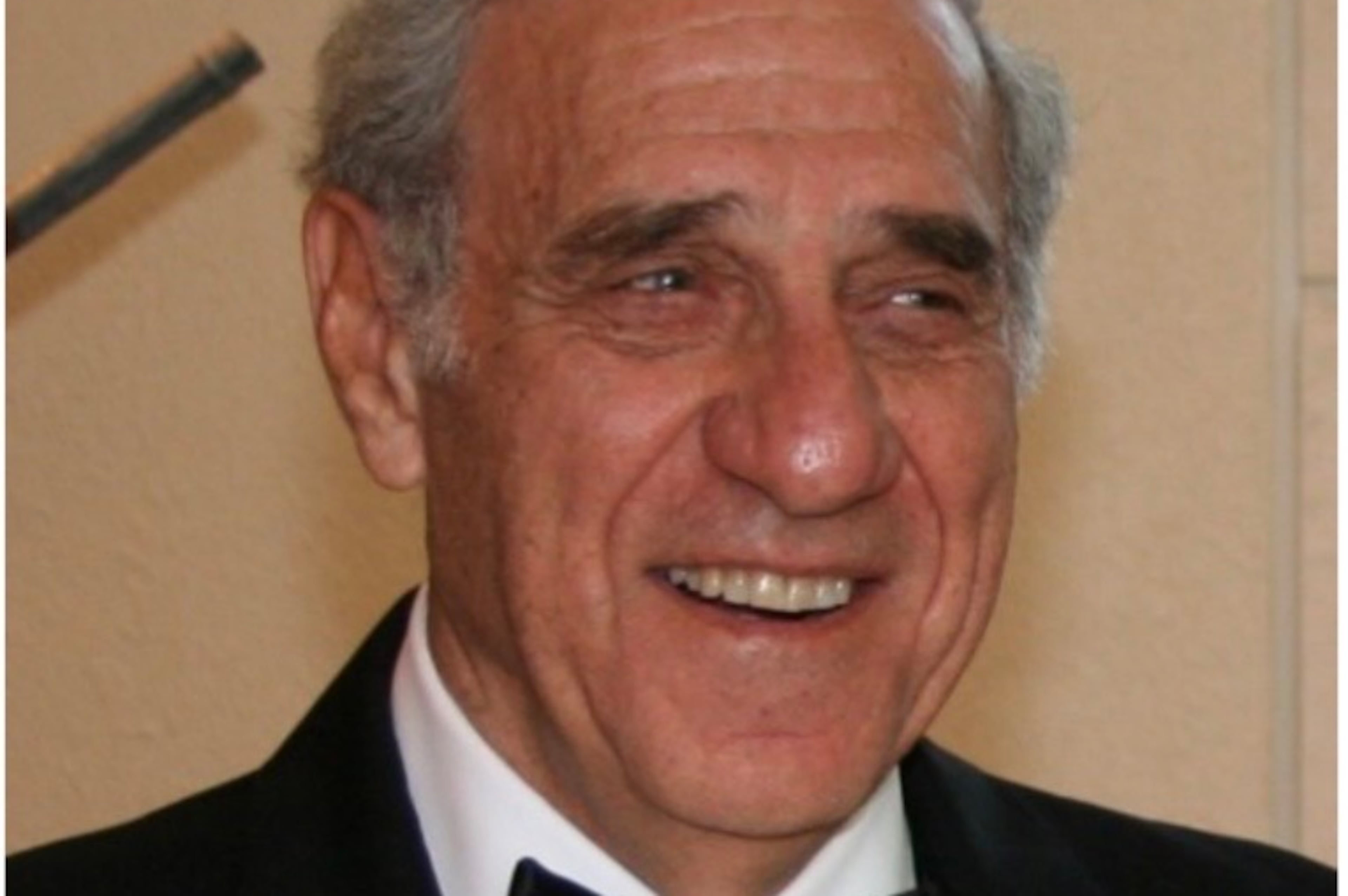

Max Osceola Jr., Florida Seminole tribal leader, dead at 70

When Max Osceola Jr. was growing up in the Seminole Tribe of Florida, many of his fellow tribe members eked out a living raising cattle and working in tourism. In traditional Indian villages along the Tamiami Trail in the Everglades, Seminole women sold handmade crafts while the men wrestled alligators for amused tourists who put money in a cup.

Poverty was rampant. Educational opportunities were few. Most families on the tribe’s Hollywood Reservation lived in thatch-roofed huts known as chickees.

Osceola referred to this period, wryly, as “B.C.” — before casinos. In 1979, the tribe began operating high-stakes bingo on their land. Since winning a federal lawsuit in 1981 that upheld their right to operate legal gambling establishments, the tribe has become wealthy running casinos, hotels and restaurants.

Osceola’s life bridged those eras — “from the stone age to the space age,” as he often put it — and, in many ways, he was a key figure in bringing about the prosperity.

A generational leader

As an elected representative of the Seminole Tribal Council from 1985 through 2010, Osceola was “one of the tribe’s longest-serving and most powerful politicians,” according to the South Florida Sun-Sentinel. His adopted brother, James Billie, was the tribe’s longtime chairman.

He signed the gambling compact with the state of Florida and helped broker the $965 million purchase of Hard Rock International, the restaurant, casino and hotel chain that the Seminole Tribe bought in 2007.

When the deal was announced, Osceola expressed his delight.

“Our ancestors sold Manhattan for trinkets,” he told reporters. “We’re going to buy Manhattan back, one burger at a time.”

Father figure

Osceola died Oct. 8 at a hospital in Weston, Florida. He was 70. The cause was complications of the coronavirus, his daughter Melissa Osceola DeMayo said.

For decades, Osceola was the public face of the Seminole tribe, and, within it, a father figure. He had a politician’s knack for remembering everyone he met, for being ready with a joke or question about their family, for making people feel heard.

Osceola could sit in a boardroom wearing a traditional ribbon shirt and be at ease with the contradiction that presented, if not the painful history of Native Americans in the United States. The Seminoles were unconquered, he liked to point out.

“He was such a proud member of the Seminole tribe,” Jim Allen, chairman of Hard Rock International and chief executive of Seminole Gaming, said in a phone interview. “But Max also understood the tribe had these great business opportunities in today’s world.”

Early life

Max Bill Osceola Jr. was born Aug. 13, 1950, in Fort Lauderdale, Florida. His father worked in construction and raised cattle. His mother, Laura May (Jumper) Osceola, was an interpreter for the tribe who spoke Creek, Mikasuki and English. She was the only woman in a delegation who drove to Washington in 1953 to argue for official tribal status and federal benefits. In 1957, the Seminole Tribe of Florida became federally recognized.

Osceola graduated from McArthur High School in Hollywood, Florida, and earned a bachelor’s degree in history and political science from the University of Miami as one of the first tribal members to graduate from college. During his council tenure, a scholarship was created to pay for college or vocational school for any tribal member.

Controversies

Osceola’s business dealings were not without controversy. In 2007, the Sun-Sentinel published a story saying he owed the IRS nearly $1 million in back taxes. He also owed the tribe $227,000 for cigarettes he sold at tax-free smoke shops he ran in the 1990s.

The article quoted a tribal official saying the cigarette matter was being resolved between the parties. As for the unpaid taxes, Osceola sounded less than contrite.

“I don’t think Native Americans even had the word tax in their language,” he told the newspaper.

Survivors

In addition to his daughter, Osceola is survived by his wife, Marge Osceola; his sons, Max Osceola III and Jeff Pelage; another daughter, Meaghan Osceola; a sister, Sharon Osceola; brothers James Billie, Lawrence Osceola, Mitch Osceola and Steve Osceola; and seven grandchildren.

When it came to making decisions for the Seminole tribe, Osceola thought generations ahead, his family said. He himself lived in the moment.

“That was him,” Melissa Osceola DeMayo said. “He was happy to be here in the world.”