How to tell what’s fine wine and what’s not

Wine authentication experts look for inconsistencies when inspecting vintage bottles.

For example, is the bottle too young or too old for the purported vintage? asked Michael Egan, a Paris-based authenticator who has testified as an expert in a number of high-profile disputes.

Experts look to see whether the bottle’s label is an original or a copy, often using high-powered magnification. And what about the foil capsule covering the cork? Is it of a different era than the vintage’s label? Egan said.

Egan also checks whether the cork has been tampered with and whether the font and design of the cork-branding are correct.

Tom DiNardo, of Winery and Wine Appraisals in Seattle, said some counterfeiters go to elaborate lengths to dupe collectors. They’ll scrape fake labels with sandpaper, apply light acids to them and even expose some labels to mold to make them appear much older than they are.

But DiNardo said that while he will appraise a wine, he will never authenticate a bottle.

“You can visually inspect the glass, the label, the cork, the foil capsule,” he said. On rare occasions, if there has been some seepage, an expert can use his or her olfactory senses.

“But to truly authenticate a bottle of wine you need to taste it,” DiNardo said. “What if it’s a vintage dating back to 1873? Who has really ever tasted one of those?”

Its grapes were picked before George Washington became president and its nuanced richness is said to leave wine connoisseurs speechless.

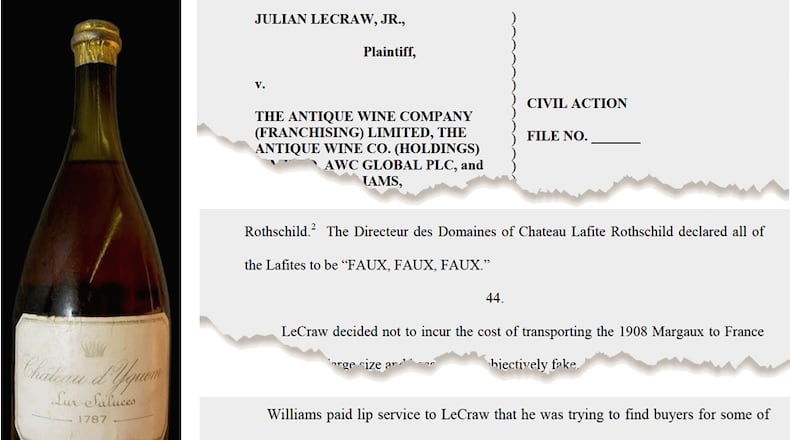

To Atlanta real estate investor Julian LeCraw Jr., the 1787 Château d’Yquem proved irresistible. In 2006, he paid $91,400 for the rare vintage, then a record-setting sum for a single bottle of white wine. LeCraw’s purchase, made anonymously at the time, caught the attention of wine collectors worldwide.

Stephen Williams, the London wine merchant who sold LeCraw the bottle, delivered it to Atlanta personally. “It might be the most expensive and pampered traveling companion I have ever had, but at 10,000 pounds a glass, I have to be sure that our client is left with a sweet taste in his mouth,” Williams said, according to press reports at the time.

But the taste in Julian LeCraw’s mouth is vinegar. He’s not sure what’s in the bottle he acquired, but he’s certain it’s not the d’Yquem. Indeed, after a visiting wine dealer told him that he should have the bottle and others he bought from Williams checked out, LeCraw hired an expert and even sent a team to France to show the wine to some of the most storied vintners in history.

"Faux, faux, faux," said le directeur des domaines at Château Lafite Rothschild, according to LeCraw's lawsuit in Atlanta federal court. LeCraw had also bought several bottles of Lafite Rothschild from Williams, including a 1784 bottle of the fabled Bordeaux for $73,000. Same story at Château d'Yquem (pronounced dee-KEMM): senior management there pronounced the 1787 and an 1847 counterfeit, the suit says.

Williams, founder and president of The Antique Wine Co. of London, denies the charge. And well he might — a broker of fine wines can’t have it put about that he’s selling counterfeit cabernet and suspect sauternes. Williams insists that the vintages are genuine and accuses LeCraw of extortion-by-lawsuit.

“The case is an attempt to extort funds from The Antique Wine Company,” the firm said in a statement. “As the legal process plays out and the facts are exposed, it will be clear for all to see the motives behind the outrageous financial demands and this unfounded and exaggerated claim.”

LeCraw’s lawyer, Shea Sullivan, said his client is disappointed by Williams’ attacks.

“Mr. LeCraw is not ‘extorting’ anything; he wants his day in court,” Sullivan said. ” … Mr. Williams’ audience will soon see that his recent promises that this lawsuit is ‘unfounded and exaggerated’ are as false as his promises to Mr. LeCraw that the wine he sold him was genuine.”

LeCraw seeks damages of at least $25 million.

A collector of wines, guitars and parakeets

Julian LeCraw Jr., a fourth-generation Atlantan, is the grandson of Roy LeCraw, an ambitious insurance agent who defeated incumbent William Hartsfield in 1940 to become Atlanta’s mayor.

At 55, LeCraw is an avid collector of all sorts of things, including guitars, watches, even parakeets (he has about 50 of them).

Two decades ago, LeCraw began collecting fine and rare wines. He bought so many bottles that he carved out a wine cellar beneath his northwest Atlanta house and then had to expand it multiple times.

He enjoyed uncorking bottles when entertaining clients and trying to close deals. In 2006, he and his wife helped raise $91,000 at a High Museum of Art auction in which winning bidders got to attend a grand wine tasting in his cellar. LeCraw also invested in wine, shipping coveted vintages to be sold by auction houses.

Only about seven years ago, the lawsuit says, Williams would visit LeCraw’s home and conduct tastings in his cellar for some of Atlanta’s top wine enthusiasts, who had dropped by to see the prized 1787 d’Yquem.

But LeCraw now alleges in his lawsuit that his prized d’Yquem is nothing more than worthless glass containing a liquid of unknown origin. The same goes for 14 other rare bottles LeCraw bought for more than $355,000 in 2006 and 2007, according to his suit, now pending in U.S. District Court in Atlanta.

"There are scams, scoundrels and whatevers," LeCraw said during a recent phone conversation. "They're out there everyday, ripping people off. It's a real shame our courts get jumbled up with stuff like this."

An explosion in trophy wines on the market

In recent years, a number of scandals have rocked the vintage wine market. In December, dealer Rudy Kurniawan was convicted in New York of selling more than $20 million in counterfeit wines to a number of wealthy collectors, including billionaire Bill Koch.

Koch, the brother of conservative industrialists Charles and David Koch, recently won a $924,000 judgment in a counterfeit wine case against a Silicon Valley entrepreneur and settled another with the auction house Zachys.

Over the past decade, the sheer numbers of “trophy” wine bottles popping up on the U.S. market have defied reality, said Michael Egan, a Paris-based authentication expert who has been dubbed “The Wine Detective.” These included the top French wines, such as 18th and 19th century vintages of Château Lafite Rothschild and the renowned 1945 vintage of Château Mouton Rothschild.

The most infamous counterfeiters infiltrated elite wine circles, impressing collectors by supplying ultra-rare bottles at events for sampling, Egan wrote in an email. “They played on the suspension of disbelief of their clients — a very slick operation.”

In LeCraw’s case, questions about the bottles’ authenticity surfaced early last year when a wine merchant visited LeCraw’s cellar to decide whether he wanted to buy some bottles or offer them at auction. The merchant had some unsettling news; he thought the bottles could be counterfeit and recommended LeCraw have someone inspect them.

LeCraw turned to San Francisco-based wine authentication expert Maureen Downey, who spent two days inspecting and photographing the bottles. Her verdict: the two d’Yquems and all of the Lafite Rothschilds were counterfeit.

Downey found that labels on some bottles that were supposedly centuries old had been printed by a computer. Other bottles had too much glue around the labels. There also were problems with some of the corks, the foil capsules covering the corks, the sediment inside the bottles, the shapes and colors of some bottles and the color of liquid in the bottles, the suit said.

‘OK, I got had; it’s been horrible’

When LeCraw confronted Antique Wine with Downey’s findings, the London merchant denied the wines were fake, the suit said. So in March, LeCraw flew his attorney, Downey, the two d’Yquems and eight Lafite Rotschilds to France and the châteaux of the wines’ supposed origin. That was when they received the discouraging “faux, faux, faux” assessment at Château Lafite Rothschild, and LeCraw decided to file suit.

Last week, LeCraw reflected on what had happened as his pet macaw, named José Muldoon, screeched loudly in the background.

“OK, I got had,” he said. “This guy, who I’ve known for years, stayed at my house. It’s been horrible. But it didn’t take me a second to decide what to do when I found out those wines were fake.”

In its statement, Antique Wine said it bought the rare wines for LeCraw from reputable suppliers and there was no fraud involved.

The company said LeCraw’s interest in wine waned after he amassed an impressive collection, and he struggled to sell the older bottles he acquired from Antique Wine because of a changing market for ancient vintage wines.

LeCraw acknowledged last week that his interest in such vintages had diminished. In fact, he said, he quit drinking wine in 2006 — the same year he purchased the d’Yquem.

About the Author

The Latest

Featured