For 42 years Alfredo’s Restaurant lay within the exotic potpourri of businesses comprising Cheshire Bridge Road. From the outside it resembled a low-slung Mississippi Delta roadhouse while the wood-paneled interior combined some of Atlanta’s most-loved Italian-American food with a peculiar gallery of artwork.

“There were clown paintings, paintings of mimes, watery scenes of Venice,” said Jim Stacy, whose Emmy-award winning PBS series “Get Delicious” profiled Alfredo’s in 2010. “It was an organically acquired collection, definitely not interior decorated, and definitely didn’t [include] your standard picture of Frank Sinatra.”

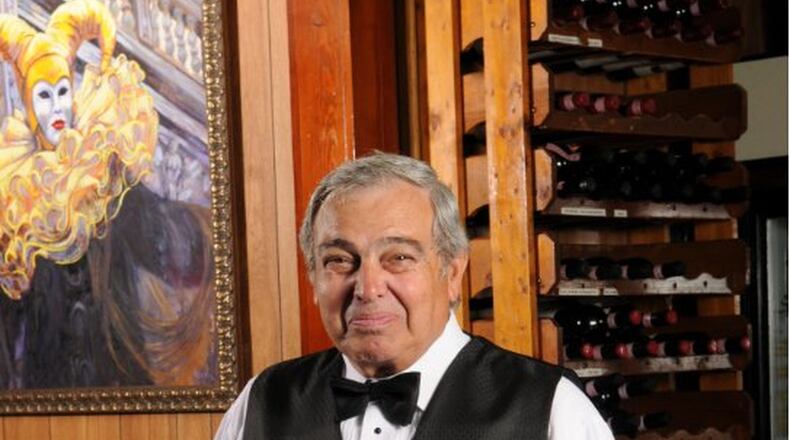

For most of its duration, Alfredo’s was the dominion of Perry Alvarez, who was busboy, dishwasher, line cook, sous-chef, chef, maître d’, host, phone answerer, reservation taker and owner. At times, like sifting varied ingredients in a single skillet, he handled all these disciplines simultaneously.

His close-cropped gray hair outlined an expansive face that erupted into a gap-tooth smile. He knew everyone’s name, and certainly no one forgot him, from longtime Georgia Speaker of the House Tom Murphy, who always held his birthday at Alfredo’s, to the bookmakers and underworld types who were loyal patrons.

Alvarez, 77, died Feb. 22 after a decline in health caused by dementia, sepsis and kidney failure.

Although Alfredo’s had a whopping 63 menu items that remained virtually unchanged for decade, it was only 2,500 square feet and sat 108. It seemed a miracle that its lifeblood flowed from a hidden, diminutive kitchen where the staff was packed like a submarine crew.

Adding to this was a certain mystique about Alvarez, whose birth name wasn’t Perry and who wasn’t Italian. He was born Francisco and grew up in Cuba. He would never visit Italy or return to Cuba, which he left at age 18, mostly because he worked every day. Adella Martinez, eight years older and a self-described “big sister and mother,” said that even as a teenager Alvarez was a “workaholio.”

Alfredo’s closed in 2016, and was razed, along with the next-door strip club, and replaced by a pair of new apartment complexes. Perry’s only child, Francisco Alvarez III, said the developers weren’t interested in including Alfredo’s or any restaurant, a decision that Perry took stoically at the time.

“What can you do?” Alvarez told the AJC in early 2016. “That’s progress. It’s all about the money.”

But Francisco charts his dad’s health decline almost from the moment of Alfredo’s shuttering. His funeral held March 7.

Francisco Alvarez Jr. was born March 3, 1943, in Havana Cuba. His father Francisco Sr. was an entrepreneur, owning real estate and renting houses while running a cafeteria that served sandwiches, coffee and light meals.

The father was called “Pancho,” while his only child was “Panchi.” Among Cuban friends and acquaintances in Atlanta, he was always Panchi, seldom Perry, and never Francisco.

“I walked Panchi to school when he was five, I was seven,” said Ricardo Reluzco, a lifelong friend. “When we got to high school, he started working at the cafeteria. My buddies and me, we’d go to the restaurant and shoot the business with Panchi. But he never partied, always worked. He liked working with his dad and his dream was to have his own restaurant.”

Alvarez left Cuba in 1962 as Castro’s revolutionary government was taking over private enterprises.

After living in Miami, he settled in Atlanta, working in two of the city’s early white tablecloth emporiums, Fan & Bill’s on West Peachtree Street and The Diplomat on Spring Street.

At The Diplomat he not only replaced a busboy named Perry, he inherited the name when fellow employees claimed Francisco was too hard to pronounce or remember. It was also at The Diplomat during an after hours robbery that Perry was shot five times, with a quick-thinking co-worker dragging him into the freezer to slow bleeding until EMTs arrived.

Alfredo’s was opened 1974 by Tony Fundora with his uncles, Raul Morales and Alfredo Fundora, the later becoming the chef and namesakes of the restaurant. They subsequently hired Perry from The Diplomat as a manager and co-partner. Perry would buy the others out in the mid 1980s.

“Almost from the beginning Perry basically took it over,” said Dennis Iannelli, an Alfredo’s waiter from 1976-90. “He was Raul’s right hand man, but Perry had better command of the language, he was better with customers. He was the best front man I ever saw.”

“It’s hard to describe how magical it was, with the food, and Perry’s personality, and all that,” Stacy said. You’d get this gorgeous piece of veal or snapper, every serving made specifically for that table, and all of it coming from that organized chaos in the kitchen.”

Alfredo’s elephantine portions were a hallmark. In 2013 Atlanta Journal-Constitution food critic John Watson wrote, “I nearly fall out of my chair when a recent Veal Chop special—a double stack of bone-in veal chops, easily 3 inches thick and wrapped in prosciutto and mozzarella, Saltimbocca-style—arrives, staring me down like a prizefighter who knows the chips are stacked in his favor.”

Alfredo’s final day came April 25, 2016. The restaurant officially closed at 9 p.m., but it stayed packed until midnight, overflowing at times with four generations of customers paying their respects and getting a last taste.

Francisco III worked at Alfredo’s 11 years and had planned on re-opening. He came close to signing a lease at a Cheshire Bridge location in 2017. But with two young sons, and with Perry’s sinking health, he realized he couldn’t go it alone. “The restaurant life is hard,” he said. “I remember that we really never took a vacation after I was in the second grade. I didn’t want to do that to my boys.”

Even as Perry Alvarez’s memory faded he talked nearly every day, in person or on the phone, with his lifelong confidante Martinez.

“I came to the U.S. in 1967 and I have lived in this house (in Tucker) for 40 years,” she said. “Panchi would stay with me when he had health trouble (he had a 2004 heart attack), woman trouble (he was married twice) or was depressed. He’d stay for a few weeks, and once he stayed for two years. I know that not having a restaurant was very hard on him. The day after he closed he called me and said, ‘Is my room ready?’ “

Alvarez is survived by son Francisco Alvarez III, daughter-in-law Audra Alvarez, and grandsons Joseph Perry Alvarez and Andrew Frasier Alvarez.

About the Author

The Latest

Featured