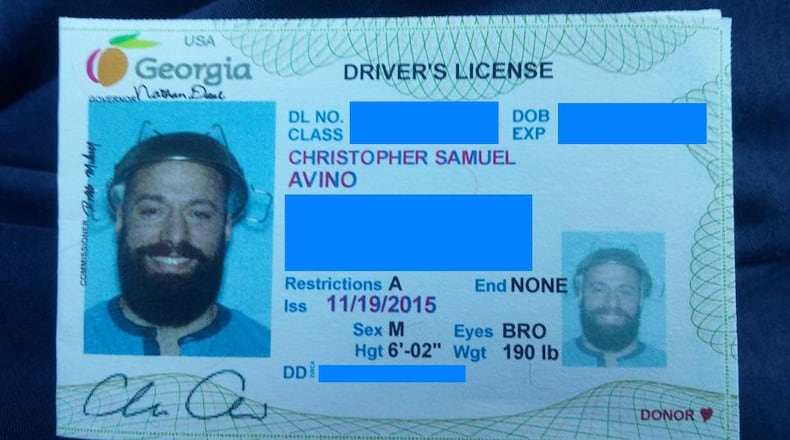

In his driver’s license photo, Chris Avino is sporting a full beard and a grin. And, oh yes, a colander on his head.

Avino, a practitioner of Pastafarianism (we’ll get there in a moment), claimed that the colander was a religious headdress and should be allowed in his photo, just as a hijab or yarmulke would be.

Though the state initially let the colander stay on his noodle for the picture, the top lawyer for the Georgia Department of Driver Services later regretted the move. Avino got a letter from the department earlier this month: “A colander is not a veil, scarf or headdress,” it said. “A colander is a kitchen utensil commonly used for ‘washing or draining food.’”

As such, Avino would need to take a new, colander-free photo.

» ONLINE EXTRA: Read the original DDS letter to Chris Avino here (.PDF)

» EXCLUSIVE: The letter Avino sent to DDS in response

Avino, who listed his parents’ Snellville address for the license but has since moved to Las Vegas, said he decided to take the picture with a colander after seeing the news that a Massachusetts woman was allowed to wear hers in a driver’s license photo. He intends to send a letter back to the state that says his First Amendment rights are being infringed upon.

“I think it’s absurd,” he said. “It’s just as valid as any other religion.”

Pastafarians belong to the Church of the Flying Spaghetti Monster, a tongue-in-cheek group that substitutes eight “I’d Really Rather You Didn’ts” for the Ten Commandments. They also believe that the Earth was created by a creature that looks like a mess of angel hair pasta and meatballs, and they pray to be touched by “his noodly appendage.” Though they have been accused of being anti-religion, members are “anti-crazy nonsense done in the name of religion,” according to the church’s website.

In her letter to Avino, Department of Driver Services general counsel Angelique McClendon said Pastafarianism “began as a satirical criticism of a local mandate to teach Creationism in schools.”

“Pastafarianism is not actually a religion. Rather it is a philosophy that mocks religions,” she wrote. “… DDS does not view satire or mockery of a religion as a religion.”

Susan Sports, a spokeswoman for the department, said the colander decision “was a new, unique issue for our team” and apologized that Avino “was initially permitted to be issued a temporary license that did not meet our high standards.”

But Pastafarianism is a religion, said Jason Millett, a Paulding County resident who was ordained in the church this summer. And even if it wasn’t, he questions Georgia’s ability to make the call.

“I don’t think it’s the business of the government to define what is or isn’t a valid religion,” he said. “He should be able to have the same religious exemption anyone else is allowed.”

Michael Perry, a law professor at Emory University who has expertise in religious and constitutional law, said Avino has a better chance of succeeding if he argues free speech than if he claims discrimination on the basis of religion. While it is clear that Pastafarians have a specific belief system, the courts have had trouble defining what, exactly, makes something a religion.

Perry said the decision to disallow the colander was the equivalent of Georgia allowing a “God loves Republicans” hat in photos, but not allowing one that says “God loves Democrats.”

“You can’t permit one, but not the other,” he said. “When you’re allowing other people to express their point of view, you can’t discriminate. That would be censorship.”

Avino, who said his Italian heritage may contribute to his affinity for Pastafarianism, said he doesn’t take the church seriously, but he is serious about what it stands for. He doesn’t think anyone should be allowed religious head coverings in their government IDs. But if some are, he said, all should be able.

“They’re just wrong,” in saying he can’t wear the colander, Avino said. “They made a mistake. I think they need to correct that mistake.”

About the Author

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured