The modern movement

A number of social justice movements and groups have developed since the #BlackLivesMatter movement against violence toward black people, specifically shootings by police officers. Many of the protests, including the protests against the handling of racial incidents at the University of Missouri, have sparked similar student protests and have been chronicled on social media. Hashtags, the # symbol followed by words, are attached to comments and posts on social media and are a way to quickly communicate the subject of a post. Here are some of the hashtags users can search on Twitter and other social media to quickly find what is going on.

#ShutDownATL

#StandWithMizzou

#AUCShutItDown

#ATLBSU (Atlanta Black Students United)

#StudentBlackOut

#BlackAtEmory

Student demands

Read the demands from protesters at more than 63 colleges and universities across the country, at TheDemands.org. The compilation includes demands for the Atlanta University Center (Spelman College, Morehouse College, Clark Atlanta University), Emory University, Georgia Southern University and Kennesaw State University.

The messages went out on social media: it was time for black college students in Atlanta to take a stand against racial injustice.

A group of about 60 students from colleges across metro Atlanta responded last week, rallying downtown in pouring rain to support black students at the University of Missouri and demanding changes on their own campuses. Hundreds more participated online, sharing messages of solidarity on their own social media pages.

Current student activism takes it to the electronic street. It’s mobile, swift and technologically savvy.

Protests that once took months or years to coordinate now can rise up in minutes or hours with a few well-placed tweets, snaps, posts and hashtags. And the Internet allows people around the world to see and read about the events as they occur, and lend support or participate in the reaction.

The use of social media is a dividing line between the previous generations of protestors, who built networks face-to-face, and their kids or grandkids, whose networks and reputations are built online. Some of the older veterans criticize social media as a way of committing little to a cause, but the digital natives embrace it for its immediacy and message control.

“A decade ago students were having lousy experiences on their campuses but there was not a way to let the world know,” said Shaun Harper, founder and executive director of the Center for the Study of Race and Equity in Education at the University of Pennsylvania.

“Now students are beginning to understand that what they are experiencing is a national phenomenon. Social media is a tool for students to help communicate their issues,” he said.

That message has played out across the country as news of campus protests and students' demands for equality has spread. From Princeton University where students are demanding former president Woodrow Wilson's name be removed from the campus because of his racist views, to Kennesaw State University, where the demands include racial sensitivity training for the campus community, protests have sometimes originated on and been disseminated by students on platforms like Facebook, Instagram and Twitter.

The worldwide connection and immediacy of social media has a benefit for protesters.

“Knowing that the eyes of the world are on you is a nightmare for universities in a competitive marketplace, because it affects image and recruitment,” Harper said. “Public shaming is not the thing that college presidents and others want. I think suddenly they are now more willing to listen, because if they are not willing to listen [they] will be embarrassed publicly.”

Colleges and universities across the country hire Harper's center to conduct campus racial climate surveys to gauge the climate on their campuses. Emory hired the center to conduct a campus survey in 2013, which it used to develop a Campus Life Compact.

Avery Jackson calls social media the “fuel” of the movement. “Social media is really powerful because it allows us to control the narrative and get our voices out while connecting to people who want similar things,” he said.

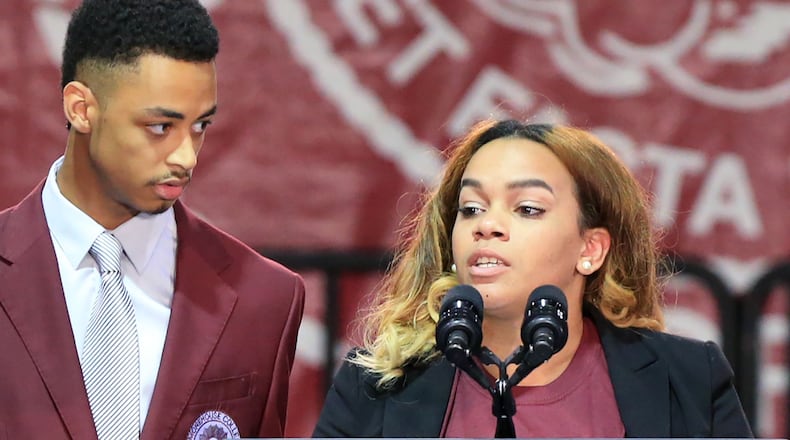

Jackson, 20, a junior at Morehouse College, helped organize the #AUCShutItDown coalition of students from Morehouse, Spelman and Clark Atlanta University, and he was one of the leaders of last week's rain-soaked rally. Social media allowed majority black students at seven metro Atlanta colleges fighting similar battles to connect and evolve into a core group of more than 100 students dubbed the Atlanta Black Students United (#ATLBSU).

The group has collectively demanded — along with specific demands for each institution — that their schools release an official statement "agreeing to take necessary action to declare the safety, justice and equality of their Black students on campus, and the Black lives of this country." They gave campus administrators a November 30 deadline to respond. Some of the schools have, with statements saying they've met with students, discussed concerns and plan to work on some of the issues.

The social media skills employed by student activists around the country are impressive, said Georgianne Thomas, a longtime civil rights activist and educator in Atlanta. “Twitter, Facebook, Pinterest, I’m on all of it,” she said. “That’s how communication is done now, that’s how news is spread.”

But can social media sustain a movement?

Today’s activists have the same passion to make change as they did during Thomas’ time in the Civil Rights Movement of the 1950s and ’60s, Thomas said. But “what they don’t have is a central theme, focus and training associated with that. It’s not that they don’t want to have it, it’s just that they don’t know to have it.”

The immediacy of social media activism doesn’t always allow for the methodical planning and organizing that was a tenet of the Civil Rights Movement’s nonviolent civil disobedience, Thomas said. “With social media you can get the crowds, so you see a bunch of people coming out feeling so emotional that it’s carrying over to their actions. (Observers) see a bunch of angry people and can miss hearing the message.”

That assessment exemplifies what Kennesaw State student Devyn Springer calls a “small rift” between some old-school activists who say social media is not a means of protest and activism.

"Actually, social media is our number one and best medium for making the movement happen," said Springer, 20, a black student leader demanding change on his campus. Springer cites last year's rally in Atlanta at CNN that drew more than 1,000 marchers, including many college students, who gathered in memory of black Missouri teen Michael Brown, who was killed by a white police officer.

“There are differences between like Civil Rights Movement activists and current activists and those differences are mostly good and are natural based on the differences in time periods,” Springer, 20, said. “The canvassing with leaflets and petitioning door-to-door that (was used in the Civil Rights Movement) worked for them, but would be impractical now. Every generation has its own methods that work for them.”

About the Author

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured