Fulton schools bring back staff and programs, but recovery’s slow

While Georgia is still rebounding from the financial hit of the recession, which took more than $100 million from Fulton County Schools, the district has managed to resurrect arts programs, hire more teachers and increase salaries.

Fulton officials say the district still has not fully recovered, and the slow pace of making up for cuts in Fulton illustrates the difficulty districts face across Georgia, especially as none yet receive the full amount of money due from the state.

“2008 was a sort of statewide peak in funding for education,” said Carolyn Bourdeaux, director of the Center for State and Local Finance and associate professor at Georgia State University.

State spending per student has dropped 10 percent since 2008 after adjusting for inflation, according to the Georgia Department of Education data. State money is divvied out to districts according to a formula, but this hasn't been fully funded since 2002. Fulton relied on state funding for about a third of its operating budget this year.

Fulton, like other metro Atlanta districts, is less reliant on state funding than most districts because of its high property values. Fulton got 59 percent of its operating budget from local revenue, the vast majority of which comes from property taxes.

FCS Chief Financial Officer Dan Jones described the period from 2008 to 2011 as the perfect storm because both state and local funding tanked. During this period, the state withheld more than $135 million that the funding formula had allotted Fulton, and Fulton’s pool of taxable property lost 9 percent of its value. As a result, the district’s operating budget plummeted by more than $100 million in just three years.

“We were getting hit from both sides,” said Deputy CFO Marvin Dereef.

BUDGET CUTS

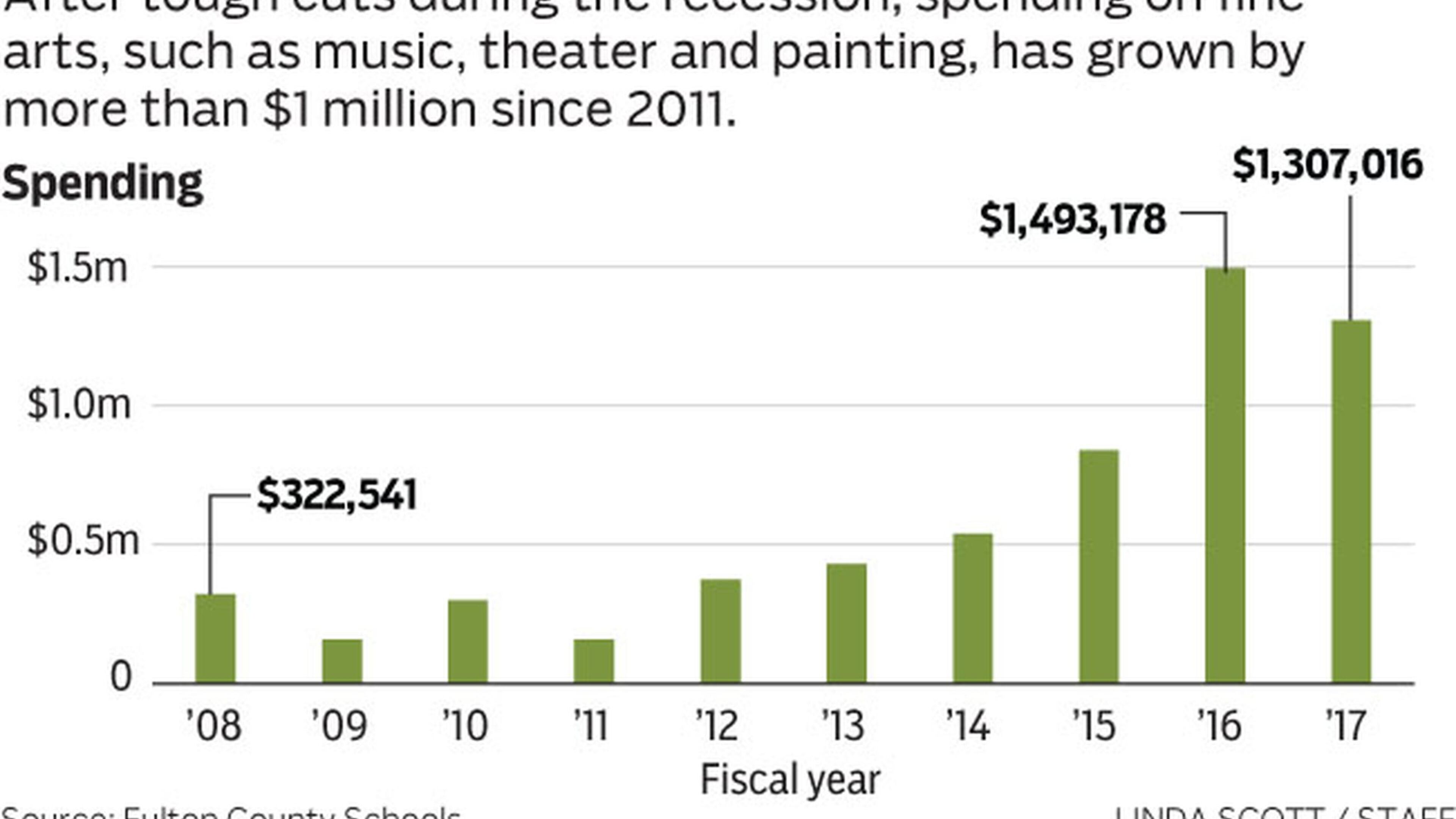

With revenue falling, the district had to make cuts. Fulton eliminated 10 percent of its staff positions, even as enrollment grew by almost 6,000 students. It cut funding for fine arts classes in half. It shortened the school year by three days.

Schools statewide made similar decisions. In a 2013 survey conducted by the Georgia Budget and Policy Institute, 71 percent of responding school districts cut days from the school year, 95 percent increased class sizes and 42 percent reduced or eliminated art and music programs.

Claire Suggs, senior education policy analyst for GBPI, said cuts especially hurt teachers by increasing their class sizes, as better student outcomes were being demanded despite reduced resources and fewer days to work.

“It’s hard to maintain teacher morale if you’re cutting their pay on top of that,” she said.

Janet Stalling was a band and orchestra director at State Bridge Crossing Elementary School when the district cut her program in 2010. The superintendent at the time, Cindy Loe, estimated that cutting elementary school band and orchestra saved the district $4 million each year.

“Music is the thing that makes everything else work a little better,” said Stalling, noting that instrumental music is a full brain activity that has been proven to improve test scores.

However, Stalling recognized the need for tough cuts.

“I don’t blame Fulton for what they did,” she said. “I guess you do what you can afford.”

SLOW RECOVERY

Fulton, like Georgia, is still inching back to where it was in 2008. Its local tax base has almost returned to what it was in 2009 at about $30 billion, a boon for local revenue. Meanwhile, the state came closer to giving FCS its full formula amount than it has in almost a decade. This year, Fulton received $7 million less than the formula specifies, a big improvement from 2010 when that gap was $55 million.

With the return of the tax base and state spending, Fulton and other school systems have slowly been adding teachers and programs that were cut starting in 2008. From 2011 to this year, Fulton made almost 2,500 new hires and increased teacher salaries, retirement contributions and benefits.

A study by the Georgia Public Policy Foundation found that teacher salaries in Georgia dropped $26 from 1988 to 2014, after adjusting for inflation. Raising Fulton's salary competitiveness in the metro Atlanta area is a major focus, Dereef said.

Over the same period, Fulton raised spending by more than $170 million in areas such as staff training, school libraries, salaries for counselors and social workers and supplemental pay for coaches. It also increased spending on fine arts by more than 700 percent.

Elementary school band and orchestra programs have not returned, though. After her program was cut, Stalling taught an after-school band program at Fulton Science Academy Private School before becoming an itinerant general music teacher for five Fulton elementary schools. In 2016, she finally became a band director again, this time at Sandy Springs Charter Middle School.

“We took a stand that we weren’t going to bring back things just because we got rid of it,” said Dereef. “We weren’t really measuring how well we got back to where we used to be, we were more measuring how well we’re getting where we’re trying to go.”

Jones says the district is still in a recovery phase.

“Until we get our full earnings from the state, and until the (tax base) gets back to growing a little bit every year, it’s hard to say we’re over the hump,” said Jones.

In Gov. Nathan Deal’s proposed 2018 budget, state funding for Georgia’s public schools would increase by more than $500 million, but districts would still miss out on $166 million they would receive if the formula were fully funded.

Fulton would miss out on $7 million for the second consecutive year, bringing the total amount Fulton has lost since the austerity cuts began in 2003 to almost $400 million.

“Georgia has really pulled back (on school funding) compared to other Southeastern states,” said Bourdeaux, the Georgia State professor. In 2001, Georgia ranked first in school spending out of 15 Southeastern states, 22nd in the nation. By 2014, it dropped to ninth in the Southeast and 39th in the nation, U.S. Census data shows.