Ex-education chief Duncan learned school could be a lifeline

Arne Duncan learned his best lessons about education not at Harvard, but on the streets of Chicago and sitting around his mother’s dining table.

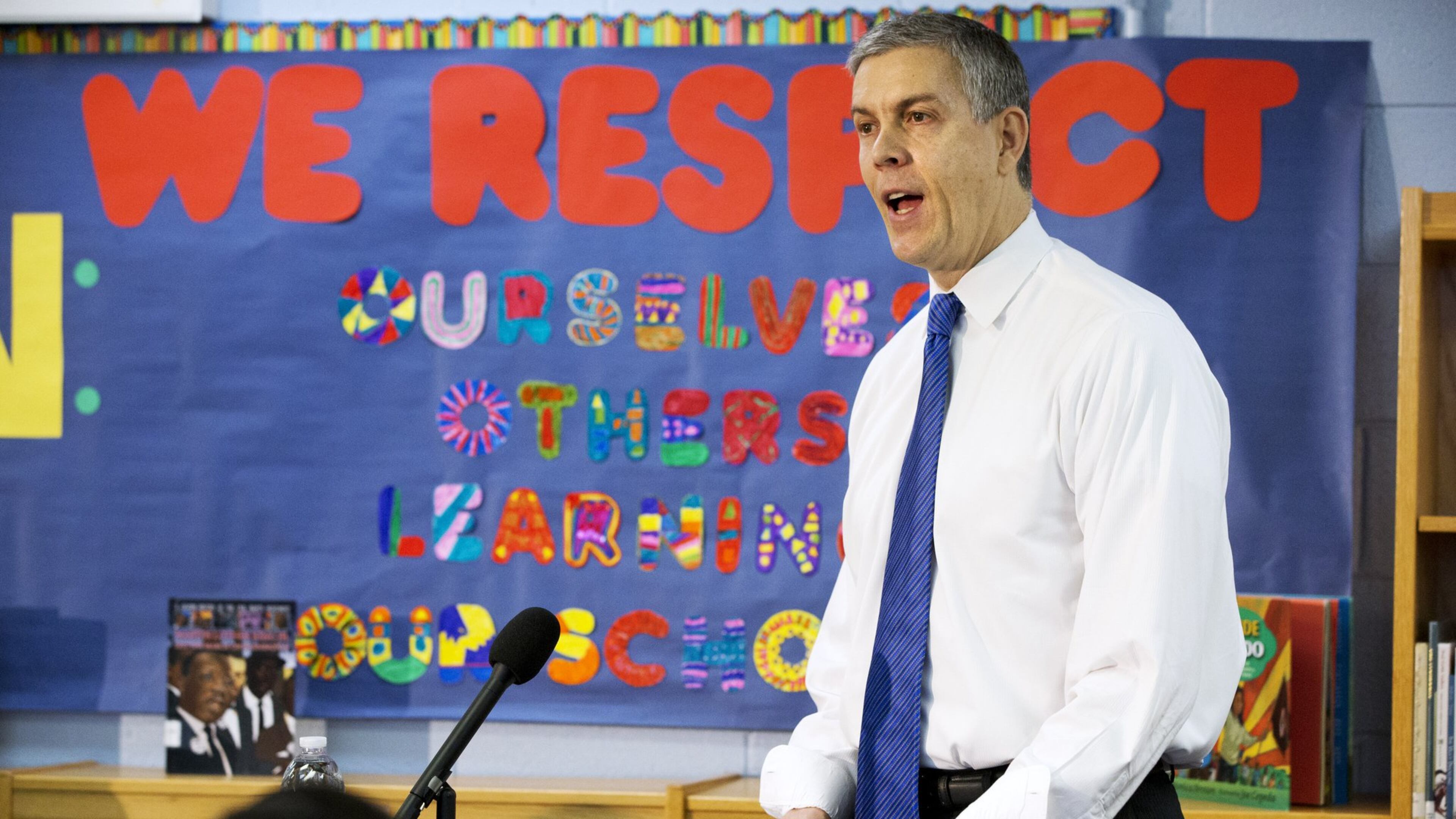

If Duncan’s name rings a bell, he was President Barack Obama’s very active U.S. Secretary of Education. Remember the furor over Common Core, lots of test-based measurements of student and teacher progress, and the Race to the Top, which brought hundreds of millions of federal education dollars to Georgia schools? Duncan helped implement those.

It’s easy to question his policies, but more difficult to question his passion. He got that honestly.

His new semi-autobiographical book “How Schools Work,” is an explanation of his values as much as it is about educational failures and successes. Two words caught my eye early in the book: Moral courage.

He got that from his mother Sue Duncan, who ran an after-school program for largely African-American kids in the Kenwood section of Chicago. He and his siblings worked and essentially grew up working in the program. I asked Duncan about it.

“I think of her courage, of going into the hood and dealing with gun violence, bringing her children in with her.”

The building she had her program in was firebombed by a gang for reasons that had nothing to do with her. She moved it down the street.

“She was working on something bigger than her and bigger than us,” Duncan said.

“She was fighting to do the right thing for kids and … (you have) the courage to put yourself in harm’s way because the work is so important.”

Some didn’t want her there. A man walked into her building one day with a gun. Sue Duncan looked him in the eye, reminded him that he learned to read sitting on her knee, and the man put the gun away and left. Another man threatened to kill her if she came back the next day.

“Mother said, if you run, you’ll never stop running,” Duncan said. She showed up the following day, with her three kids. The man didn’t.

On her daily round of picking up kids in a van, she turned into an alley for a pickup and drove into the middle of an attempted murder. She backed out, fast, but continued to return for the child.

The 6-foot-5 Arne Duncan went to Harvard on a basketball scholarship, but eventually returned to Chicago to work with his mother and others, eventually rising to run Chicago Public Schools. His connection with the Obamas took him to Washington, where the fighting styles were a good deal different, but his passion remained high.

As a boy in Kenwood, he learned if a teenager got a diploma, he or she got a chance at a way out. Some young men his age who didn’t, who he knew and played basketball with, died.

“That scars you in ways that is hard to understand … at that time I didn’t have any friends who were killed who had a high school diploma,” Duncan said. All those who were killed had dropped out.

“For me, I started to see education as literally a life-or-death issue.”

And he grew up with an inherent understanding of why poor kids going to bad schools were being cheated. They did not have the same chance at the American dream, as having a decent life, as kids from affluent neighborhoods.

“Education runs on lies,” are the first words in his book.

That may help explain some of his actions while leading the country’s education department. He saw a need for change. Lots of it. Fast. He ended up alienating folks on both ends of the political spectrum.

He still wants change and is back where he started, in Chicago. He is the managing partner of Chicago CRED. It’s a helping agency that targets the young men most likely to be the shooters or the shot, giving them the skills and finding them the jobs they need to have options in life.

“I am trying to give guys a reason to put down guns … a way into the legal economy … that is huge focus of my work now. A path out of the streets.”

He’s back where he started. And he loves it.

“I didn’t fully realize this, but being back in the city after seven years in D.C., I needed that, my soul needed that more than I realized.”