When Fulton County Superior Court Judge Robert McBurney first read Leslie Singleton’s letter last year, he assumed there was a mistake.

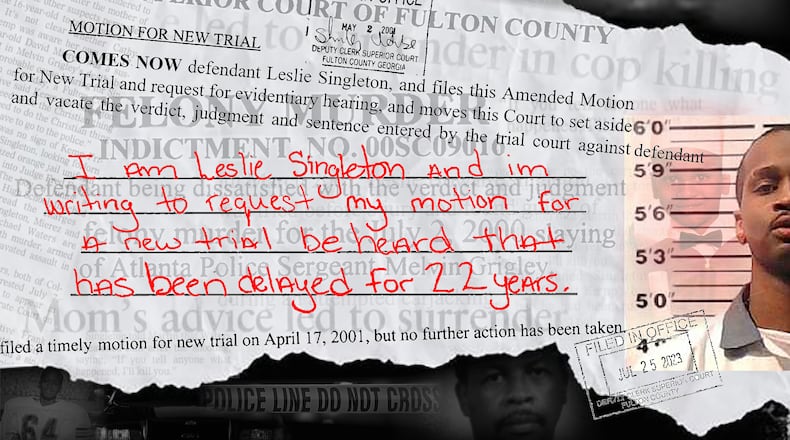

The letter was straightforward and to the point: Singleton, an inmate at Coffee Correctional Facility, wanted to know what was holding up his motion for a new trial.

What was stunning was how long he had been waiting: More than 20 years.

“I just know that this is beyond delay to the point of negligence or remiss,” Singleton wrote in July, explaining that he had been a juvenile when his case began.

For the judge, who was sent the letter as part of Fulton County Superior Court’s review process for new filings in cases over 10 years old, the letter was “boggling.”

“Like, there’s no way this is a case from the 2000s,” he told The Atlanta Journal-Constitution, explaining that a motion for a new trial must be filed within 30 days of a defendant’s initial sentencing. And while a decision can sometimes take a few years — especially if court transcripts come in late — they shouldn’t take two decades.

But when the judge tracked down the old case file, what he found was just as Singleton had described: A March 2001 conviction and an appropriately filed motion for a new trial three weeks later, then 22 years had passed with no hearing or decision.

Singleton, who at 17 was convicted of felony murder for his participation in a carjacking gone awry and sentenced to life with parole, had slipped through the cracks of the court system.

In Georgia, defendants are offered the opportunity for a second review of their case in the form of a motion for a new trial and/or an appeal. If a motion for a new trial is filed, however, a defendant cannot move to the appellate phase until a judge makes a ruling.

Singleton has been stuck in legal purgatory.

Credit: Courtesy of Singleton family; Georgia Department of Corrections

Credit: Courtesy of Singleton family; Georgia Department of Corrections

Complicating the case is the fact that Singleton was sentenced in 2001 as one of the first cohorts of kids in the state to be tried as adults under SB440, a 1994 law designed to provide harsh punishment to juveniles who commit violent crimes. In other words, Singleton got lost in an adult system despite being a child who was dependent on the state for navigation.

“It’s a procedural tragedy,” McBurney said, emphasizing that he couldn’t comment on the specifics of the case, just the process that failed Singleton, who is now 40.

“Thank goodness this man wrote this letter,” the judge said.

Pinpointing what went wrong is a challenge. It appears to be a series of common errors, highlighting the fallibility of the criminal justice system, which is made up of people who can make mistakes.

In December, disturbed by the finding and eager to address Singleton’s motion, McBurney asked a local appellate attorney to take on the case. It was so old that the state’s current indigent defense program, Georgia Public Defender Council, didn’t exist when the case began. Because of that, the county will foot the bill. A hearing is scheduled for Monday.

The surfacing of Singleton’s case two decades later — thanks to his initiative and consistent letter writing — is a shock to the system. It also places the spotlight on a less discussed but critical part of the trial process: Post-conviction reviews.

Credit: Leslie Singleton

Credit: Leslie Singleton

This step provides a check and balance on the criminal justice system, according to Cassandra Robertson, a law professor at Case Western Reserve University who specializes in professional ethics and procedural law. When there is a breakdown, it can call into question the fairness of the entire court system, she said.

“It’s not justice,” Robertson said, ”if an essential issue in a case just isn’t getting decided.”

While a delay of this magnitude would be problematic on its own, a review of the 2001 trial raises a host of questions about Singleton’s original defense. Specifically, the AJC found that Singleton’s trial attorney was repeatedly flagged by the state Supreme Court for failures in representing indigent defendants.

The record, which leaves open a possibility of ineffective counsel for Singleton, underscores why a post-conviction review is important.

It’s a reality that leaves Singleton, and his current attorney David Hoort, to contend with two questions.

The most obvious: How did this happen? And the more pressing: Is it even possible to undo such a wrong?

A cop killed, a teen convicted

Stitching together any case 20 years later is a challenge, but Singleton’s is particularly messy, confusing and tragic.

According to court transcripts and a psychological exam completed by Singleton this spring, in the summer of 2000, the then-16-year-old had just finished 10th grade at North Clayton High School and was on summer break when he and two friends decided to rob a drug dealer to get money. In the 2024 psych eval, Singleton said the intention was to get money to bail out his mom, who had recently been arrested for driving under the influence and obstructing an officer.

On July 1, 2000, the trio — Singleton, Michael Waters, and David Brandon Mierez — set out with Michael Myers Halloween masks, gloves and a gun.

As they walked to their destination they decided to try stealing a car. Sometime after midnight on the morning of July 2, they saw a couple fighting in a BMW parked in a driveway in College Park.

Waters, with the gun, approached the car. He got the couple — Melvin Grigley and Debbie Blalock — out of the car and told Singleton to get into the driver’s seat, which Singleton did.

Credit: Atlanta Police Department

Credit: Atlanta Police Department

What the boys didn’t know, according to a 2000 AJC article, was that Grigley was an off-duty Atlanta Police Department sergeant.

Grigley, according to the trial transcript, took out a gun and began shooting. Waters shot back as Singleton, who was shot twice in the left arm, scrambled out of the car and ran.

Waters’ shot was fatal. He later told police the teens didn’t know Grigley had died until they saw it on the news the next day.

The case was heartbreaking. Grigley, a 26-year veteran of APD and a father of four, died at age 51.

Waters took a plea deal that November. Singleton’s case went to trial on March 13, 2001. He turned 17 the day before.

At the trial, which was presided over by Judge Doris Downs, the state argued that while Waters pulled the trigger, Singleton planned the robbery by providing the gun, masks and gloves.

Gary Guichard, an assigned public defender, represented Singleton. He made the argument that there was no concerted effort to kill someone that night and that what happened fell on Waters, who pulled the trigger.

Credit: AJC archive

Credit: AJC archive

Despite Singleton being the youngest defendant — Waters and Mierez were both 17 at the time of the crime — and not being the shooter, he received the most severe sentence, as his co-defendants were given plea deals to testify against him.

On March 21, 2001, Singleton was convicted of felony murder and aggravated assault. He was sentenced to life with parole, which at the time required a minimum sentence of 14 years before being considered by the parole board, and 20 years for the assault, which could be served concurrently.

Adding a twist to the case is the fact that the gun used to commit the crime was a Fulton County sheriff’s weapon.

On June 30, one day before the homicide, an officer reported a missing gun, stating he had been robbed while at an apartment complex in Clayton County. The gun was in his backpack. A week after the Fulton County case was finished, Clayton prosecutors filed armed robbery charges against Singleton, who had given the gun to Waters.

While Singleton maintains that he found the gun, he was convicted that July and sentenced to life in the Clayton case.

New attorney, new chance

Hoort, who began reviewing the case files in January, was initially reticent to accept McBurney’s request to take Singleton’s case.

A former Michigan judge who moved to Georgia to be closer to his grandchildren, Hoort was busy with other legal work.

At face value, his task is simple: Review the transcripts and assess whether Singleton got a fair trial in 2001.

In actuality, it is daunting.

“It’s almost difficult to present our case, if not almost impossible,” Hoort said.

One notable black hole surrounds Singleton’s trial attorney: Guichard.

Guichard was the trial attorney for Michael Lewis, a teenager sentenced as an adult back in 1997. An AJC article on Lewis’ release in November reported that his co-counsel subsequently testified that Guichard had provided ineffective counsel.

Further research into Guichard reveals a series of questionable choices by the attorney.

In 2006 and 2009, his license was suspended by the Georgia Supreme Court. The files are so old that court officials could not say with certainty what prompted the suspensions. A court spokesperson said in one of the cases it looks like it was because he did not properly respond to an investigation into a complaint. In 2010, the court publicly reprimanded him as a response to complaints by three indigent clients during his time at the Metro Conflict Defender Office.

This record, coupled with questions Hoort has now about the way his client was represented, is the basis for one of the attorney’s claims in his new motion of ineffective counsel. But there is a snag: Guichard died in 2014.

“The norm is you can’t accuse somebody of being an ineffective lawyer unless you call that person as a witness,” Hoort said. “Give them an opportunity to respond to your allegations.”

These gaps make it difficult for Hoort to accurately assess the decisions Guichard made, and whether they were in Singleton’s best interest.

Credit: arvin.temkar@ajc.com

Credit: arvin.temkar@ajc.com

Because Hoort doesn’t have access to Guichard or his trial notes, Hoort doesn’t know whether Singleton had been offered a plea deal, as his co-defendants were. Fulton County could not answer this question for him, he said.

Silver-haired, with a trim mustache, Hoort is particularly struck by his client’s age at the time of the 2001 trial. In the two decades since Singleton was tried, the U.S. Supreme Court has made significant rulings on the sentencing of children, noting that they have diminished culpability, as their brains are not yet fully formed, and they are more prone to peer pressure and reckless behavior without thought of consequences.

These developments created a complicated issue for Hoort. He is tasked with assessing a trial that happened two decades ago but with the frame of mind of a person living in 2024 and aware of these changes.

Anatomy of a delay

While Hoort’s main focus is to seek a new trial, it’s hard for him to not be curious about how his client slipped through the cracks.

The docket, recently uploaded to Fulton County’s online system, reveals a few clues.

Three weeks after the trial, on April 17, 2001, Carl Greenberg, an assigned appellate attorney, filed a boilerplate, one-page motion for a new trial. While this is common as attorneys aim to make the 30-day post-sentence deadline, they usually file an amended motion tailored to the case once they review the transcripts. For Singleton, this never happened. And the court failed to schedule a hearing.

In May 2001, one month after the trial, transcripts were filed. The next and last apparent activity in the case occurred in August 2005. The prosecutor’s office wrote a letter noting that it had been four years and the case had not moved forward. They suggested a new attorney be placed on the case.

Perhaps this could have been a turning point for Singleton.

But a week later, Greenberg filed a response saying he would stick with the case and didn’t want to amend his original motion. He said he was prepared to argue the case as soon as the court scheduled a hearing. A hearing was never set.

Over the years, the court docket shows, Singleton sent various letters to the court, requesting documents and transcripts. But until the letter from Singleton hit McBurney’s desk in July, the case went dormant for two decades as Singleton waited in prison.

“It's not justice if an essential issue in a case just isn't getting decided."

In reviewing the sequence of events, Robertson, the Case Western Reserve University law professor, told the AJC she sees a systemwide failure.

The appellate attorney failed to pursue the case with reasonable diligence, and the judge had a responsibility to keep the docket moving. The prosecutor’s office, possibly the least to blame, had a duty to pursue justice and stay on top of the case as representatives of the state.

And while Robertson agrees Singleton’s case is unique due to the sheer number of oversights and dropped balls, she contends it’s important not to write off the case as an anomaly.

“Each of the points of failure, by themselves, are super common,” she said.

The Office of The Fulton County Court Administrator did not respond to questions about the delay.

Judge Downs, who retired in 2018, said she could not comment on an old and pending case.

And Greenberg had few answers. “It sounds like some attorney down the line dropped the ball and he’s entitled to an appeal,” the former attorney said. There is no evidence that the case was ever assigned to a different attorney.

When asked whether that attorney would have been him, he said he didn’t believe so, but he also said he couldn’t remember anything from so long ago.

“I feel bad if he didn’t get an appeal if he was entitled,” he said.

Court sets new rules

When speaking about the case, McBurney contends Singleton’s case is an unusual scenario and the problems it highlights are not widespread.

“I talked to my colleagues and no one else has something that’s this old,” the judge said, pointing out that in recent years rules were passed to address such issues.

In 2018, after hearing an appeal from 1997, the Georgia Supreme Court issued a strongly worded opinion on the state’s backlog of post-conviction cases. The following January, the court issued new rules to try to curb the problem.

Trial courts now must schedule status conferences regarding motions for a new trial within 120 days of sentencing. Local superior courts must also submit biannual logs of all pending motions for new trials or cases awaiting transmission for an appeal.

A review by the AJC, however, raises questions about the impact of such a rule.

According to the Winter 2024 report supplied to the court by Fulton County Superior Court, there are over 350 cases on the county’s list. Of those, roughly 20% are from cases that started a decade or more ago.

“It's a procedural tragedy. ... Thank goodness this man wrote this letter."

The state Supreme Court’s website notes that the Fulton list is a “preliminary submission, subject to future revision.” Fulton County Superior Court did not respond when the AJC sent questions to fact-check the data.

Compounding issues of accuracy, Singleton is not found on the list, which raises questions about the efficacy of the Supreme Court’s reforms.

The absence of his name also underscores the possibility that there could be others waiting in judicial limbo.

Defense attorneys and advocates second this fear and believe it highlights the necessity of post-conviction reviews.

The procedures are meant to guarantee a second set of eyes, said Andrew Fleischman, a Georgia trial and appellate lawyer. They are a fact-check, an acknowledgment that systems are made up of people, and people can make mistakes.

“Even if you don’t win the appeal, it’s important to at least give your clients the sense that, ‘Hey, someone beyond the trial took a look at this,’” Fleischman said.

What happens next

On April 29, Hoort submitted his 39-page motion for a new trial. It was 38 pages longer than the boilerplate motion Greenberg filed in April 2001 and doubled down on in 2005.

The Fulton County District Attorney’s Office responded on June 17. They maintain Singleton received a fair trial and sentence.

A hearing has been scheduled for Monday, at which point McBurney will hear evidence from both sides and will have to determine whether Singleton, 23 years later, deserves a new trial.

If the judge denies the motion for a new trial, Hoort can appeal, ultimately, to the Georgia Supreme Court, whose decision would close the loop on this two-decade question mark and could open the door for the actual appellate process.

“Even if what the Supreme Court ultimately says is ‘That conviction was a solid conviction, that sentence is valid,’ even if it is an affirmation of what happened in trial court 20 years ago, no one should have to wait that long to get that answer,” McBurney said.

In anticipation of this development, Hoort had Singleton’s older sister, Monique Davis, send letters to the victim’s family.

“We wanted to let the family know that the amended motion for a new trial is not to excuse or minimize Sgt. Grigley’s tragic death,” said Hoort, who explained Singleton couldn’t write the letters himself because defendants are not supposed to have contact with victims’ family members. The letters aimed to ensure family members weren’t surprised by a hearing that was supposed to have occurred two decades ago.

The AJC reached out to Grigley’s family members but did not hear back.

For Singleton, this moment is met with conflicting feelings. His case might have been stagnant, but he and others who’ve worked with him over the years say he has grown and matured.

“He’s a totally different person,” said Shirley Brady, Singleton’s GED instructor with Georgia Department of Corrections. She met him during his early days of incarceration and has stuck around as a second mother figure.

“I immediately gravitated to him, because I saw something good in him,” she said, explaining that when they met, she saw a misguided and unnurtured kid who “wanted to be better but he didn’t know how to be better.”

Miraculously, despite incarceration, Singleton found that path.

He has taken on various leadership positions while in prison, earned his GED, completed numerous work courses and self-published an e-book on positive thinking, according to notes that accompanied his psychiatric exam this spring. The reviewer examined his prison disciplinary records through December and noted that the last sustained violation against him was in 2014.

“Mr. Singleton has shown considerable rehabilitation, remorse, and regret for his association with the incident,” the psychiatrist who performed the exam wrote.

Writing via his girlfriend Paris Adamson, to whom an AJC reporter sent questions, Singleton explained he felt relieved that he was finally getting the opportunity to have his case reviewed. He also expressed fear — given his previous negative experiences with the criminal justice system — that the outcome would be more of the same roadblocks.

“I was still kinda skeptical as to what is really going on,” he wrote, pointing out that, in addition to having his motion lost for two decades, he has been denied parole twice since becoming eligible in 2015.

Steve Hayes, a spokesperson for the Georgia State Board of Pardons and Paroles, said he could not comment on the specifics of Singleton’s case. He said parole was denied in 2015 and 2022 because the board decided Singleton’s release “would not be in the best interest of public safety, also citing an insufficient amount of time served due the severe nature and circumstances of the crime.” Singleton is next up for consideration in 2027.

This circumstance means he has put more weight on the trial and appellate system to get another opportunity to come home. And while he maintains a healthy dose of doubt after the court system lost track of him, he is also aware there’s one big difference this time: His attorney. Hoort -- or “King David,” as Singleton has christened him.

“King David is what I call him inside, because he moves like a real, upright character out of the Bible,” Singleton wrote, explaining that Hoort has shown diligence and great communication since being assigned the case last winter. The attorney has even offered to help review the Clayton case.

“I’ve never had a lawyer as dedicated and welcoming as King David,” Singleton said.

It’s a turn that underscores one of the biggest ironies of Singleton’s situation: The length of time he has waited has escalated his case to such a red-alarm level that he now has the benefit of a judge hand-selecting an attorney to take on his case, and a lawyer who has the time and additional help to review the original trial transcript with a fine-tooth comb.

Singleton, aware of his shift in circumstances, expressed gratitude. He also acknowledged how this change shows the seeming randomness of the justice system, which is still human and fallible in all the ways his case has highlighted.

“I think about how many more kids are in similar situations,” he told the psychiatrist this spring, when he was asked how he’d feel, should he get the opportunity to come home.

“It won’t be a big celebration for me,” he said, “the same system is happening.”

About the Author

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured