Emory study on PAD, peripheral artery disease, focuses on amputations

In early 2021, Tony Black’s left foot suddenly started to swell after a severe bout of COVID-19. He went to an urgent care clinic and was told it was likely gout.

But with his foot swelling to the size of a football, Black said the gout diagnosis didn’t seem right. The veteran Army medic went to Atlanta VA Medical Center and was eventually diagnosed with peripheral artery disease (PAD), a circulatory problem that develops when narrowed arteries reduce blood flow to limbs.

By then, the tissue damage to his left foot was so extensive that an extreme measure was needed to save his life. In March 2021, he underwent a below-the-knee amputation.

“I keep going but physically and psychologically, it’s been real bad,” said Black, 66, who lives in Perry, Ga.,

Leg or foot pain while exercising or even walking a short distance can indicate a common but serious condition that is often ignored and overlooked. Delays in care can lead to catastrophic complications.

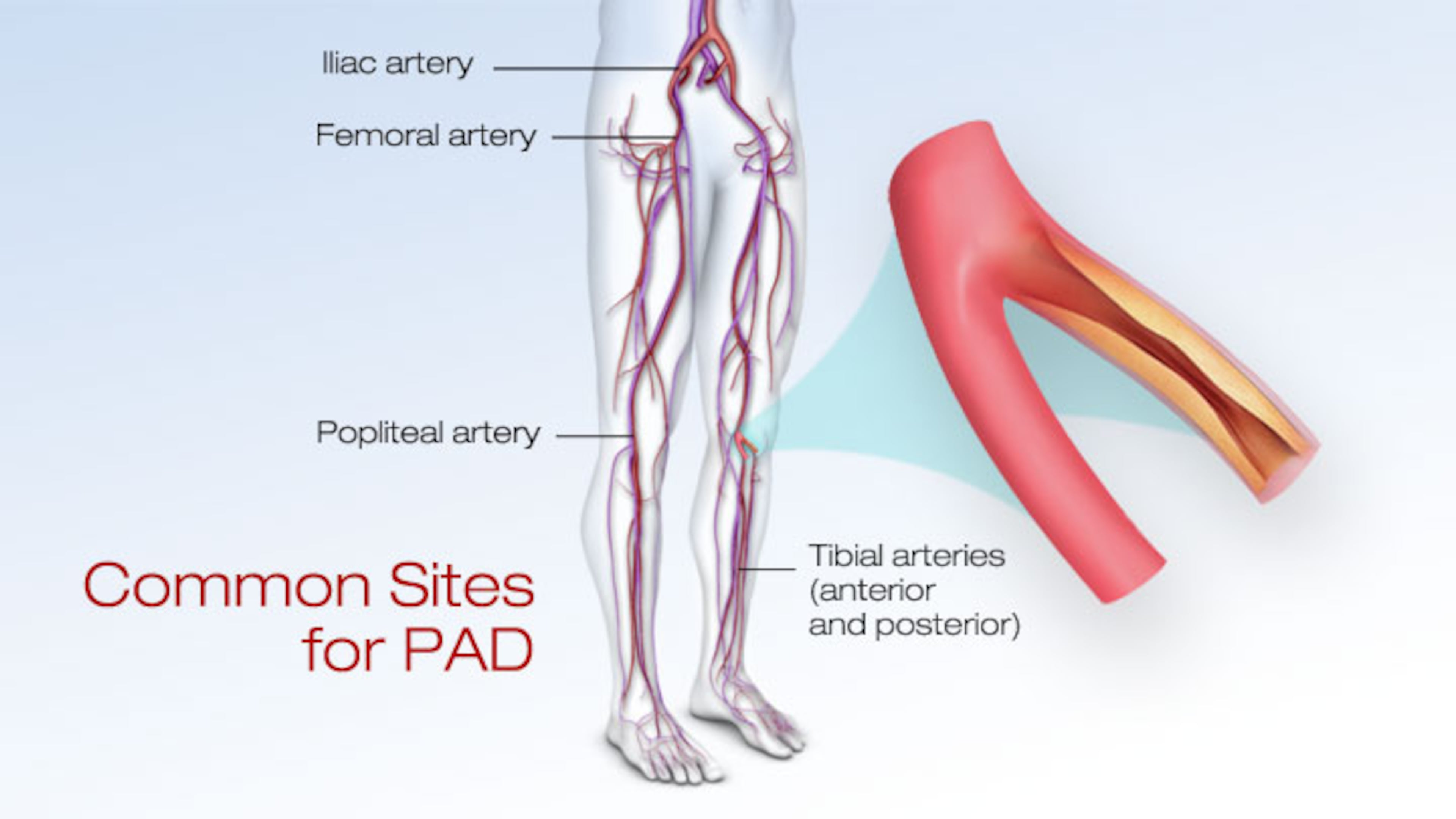

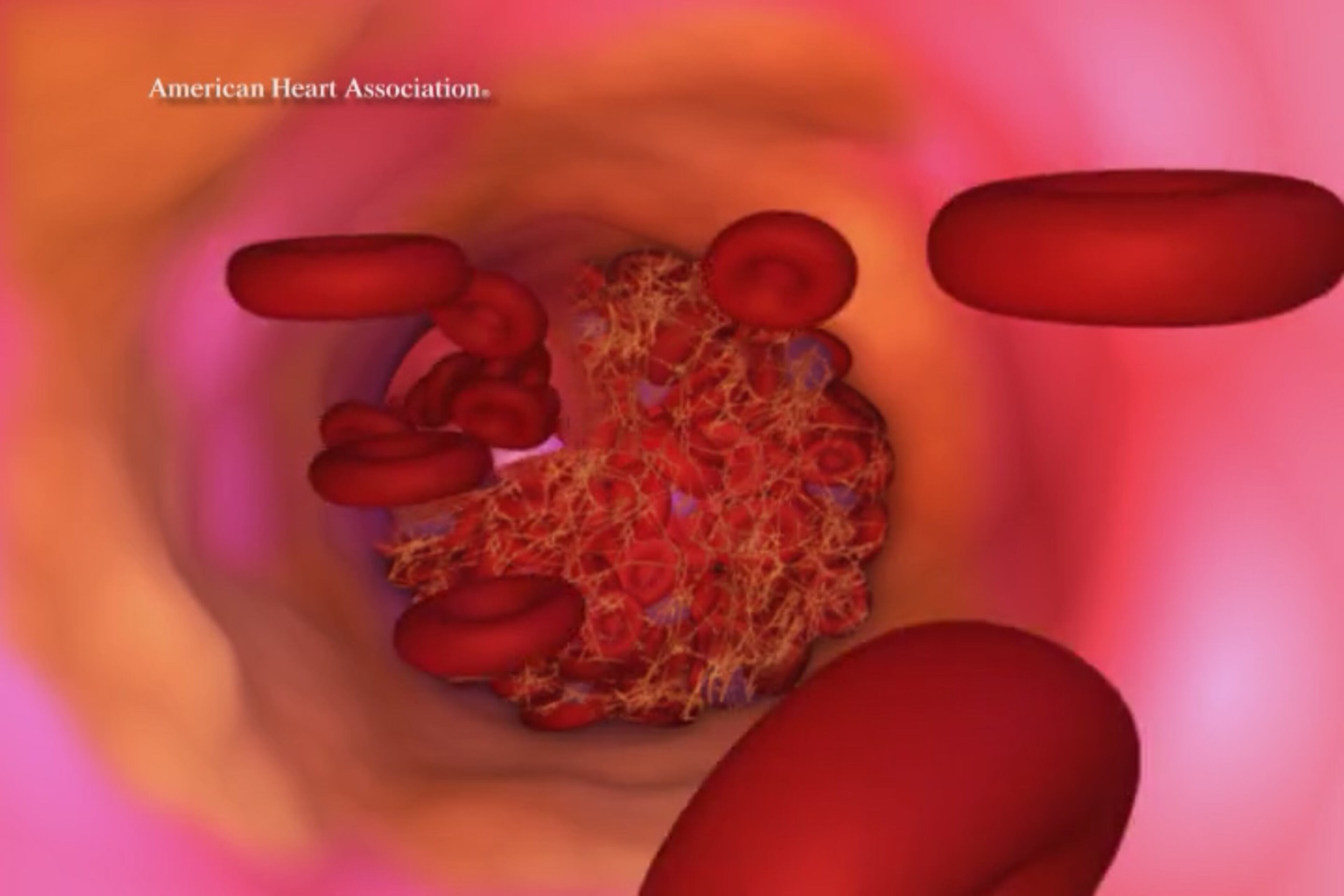

As many as 12 million Americans have PAD, primarily caused by atherosclerosis, the buildup of fatty plaque in the arteries, according to the Cleveland Clinic. With PAD, the arms or legs — but usually the legs — don’t receive enough blood flow to keep tissue alive. It is a leading cause of 185,000 leg and foot amputations each year in the U.S.

A new Emory Healthcare study examined a group of people who were not diagnosed with PAD early enough and suffered devasting amputations. The study, published last month in JAMA Surgery, focuses on 19,396 veterans who had severe PAD and limb loss over a recent 10-year period. The researchers delved into why they didn’t get treatment early enough to avoid life-threatening complications such as skin ulcers that become gangrenous and result in limb amputation.

Many people with PAD don’t realize they have it, putting them at risk for strokes, amputations and even death. With early diagnosis of PAD, monitoring and treatment, however, limb amputation is preventable.

Dr. Andrew Klein, a cardiologist and vascular specialist at Piedmont Heart Institute, said PAD cases are expected to triple over the next three decades, and yet, many people — even clinicians — remain unaware of the disease. Even in those with symptoms, doctors often fail to diagnose it, though there is a simple, non-invasive test.

“PAD’s a major problem,” said Klein. ”There are so many people who are not getting treated or not being looked at more than anything else.”

“I have countless cases of people who have a diabetic ulcer [an open sore] for many, many years and it is not healing,” Klein said. “And they somehow find themselves to me or another specialist and it’s like, ‘I know why it’s not healing.’ The underlying cause may have been diabetes, but the vascular insufficiency just compounds the issue and leads to major problems.”

The disease is especially severe for Black people, who are twice as likely to have PAD as whites and up to four times more likely to require amputation as white people, according to research published in the Journal of the American Heart Association. Black Americans, already facing barriers to care, are more likely to have traditional risk factors for developing PAD such as high blood pressure, tobacco abuse, and type 2 diabetes — and they also tend to be diagnosed at a later stage of the disease.

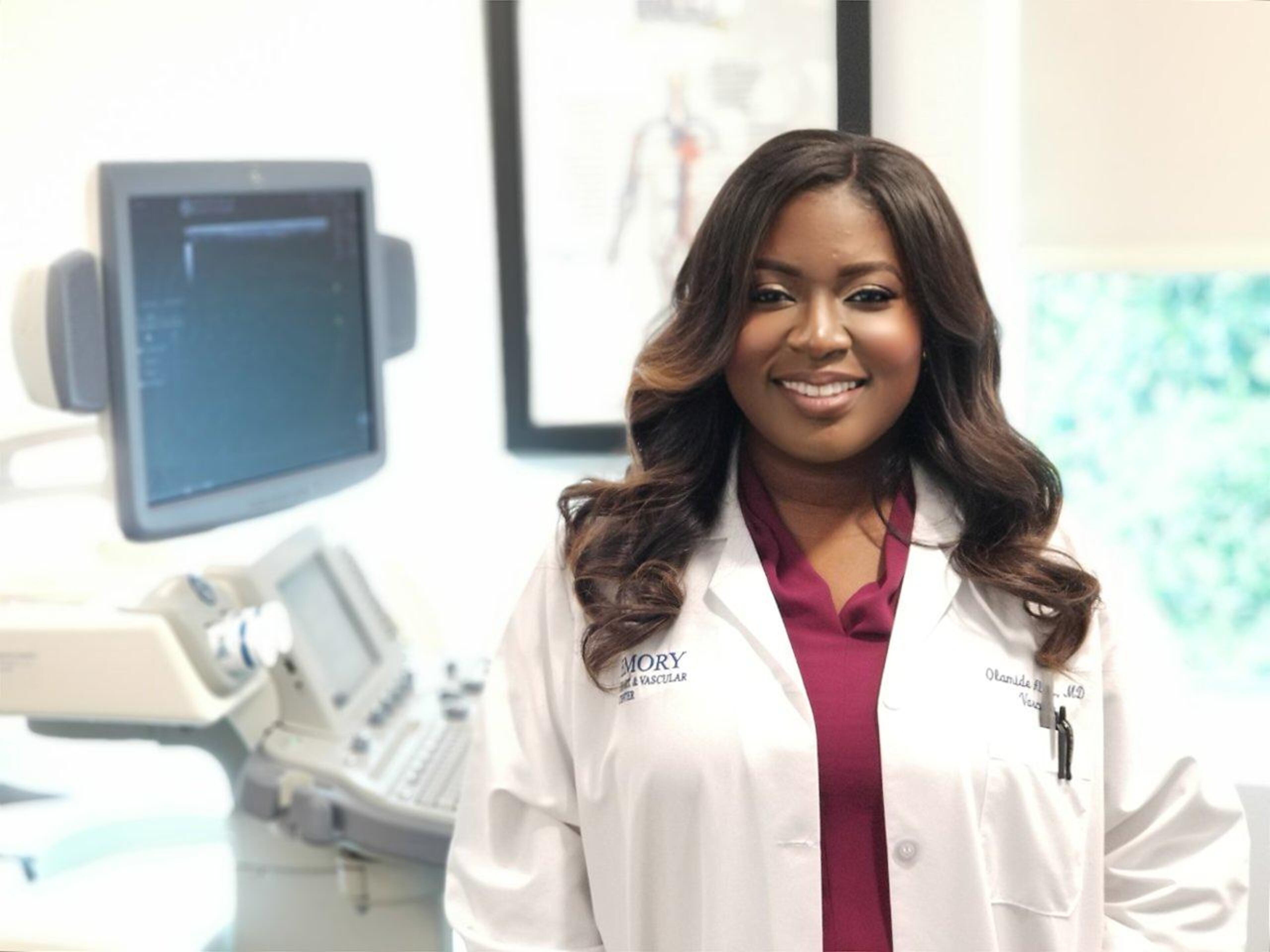

Data suggests that Black patients don’t get vascular assessments at the same rate as white patients in the general population. But Dr. Olamide Alabi, a vascular surgeon and lead author of the Emory study, said Black veterans were found to be just as likely or even more likely to get a vascular assessment in the year prior to amputation as other racial groups.

Alabi said many PAD cases are likely missed because many patients don’t get a vascular assessment at doctor visits. Vascular screenings often start with an ankle-brachial index (ABI) test, a simple way for doctors to check how well blood is flowing in the legs. The ABI test compares the blood pressure at the ankle with the blood pressure at the arm, using a Doppler ultrasound to visualize a blocked or narrowed femoral artery.

Patients with severe PAD who develop gangrene have up to a 25% chance of having to have a foot or leg amputated within one year of diagnosis, according to USA Vascular Centers, a network of facilities treating

Vascular specialists say many cases go undetected because patients have limited or no access to a primary doctor. PAD is common among older adults, affecting one out of every 20 people over the age of 50, according to the Advanced Heart and Vascular Institute, a network of providers focusing on early diagnosis and minimally invasive treatments for PAD.

With access to comprehensive medical records of veterans, Alabi was able to analyze the treatment and outcomes of thousands of PAD patients. The Emory study found that patients who live more than 13 miles from their primary care provider’s office were 12% less likely to have a vascular assessment in the year prior to amputation.

But that’s only part of the problem, Alabi said. Even among those seeing a primary, many are not getting assessed for this progressive disorder. The study found that in that year before amputation, 8% of the 19,000 veterans studied had no primary visits and 30% of the veterans did not get a vascular assessment.

“We know that patients with peripheral artery disease have higher rates of limb loss and also higher rates of mortality,” said Alabi, “and there’s not really been a huge effort to try to determine why exactly, or to try to prevent those things per se...”

She also lamented how little has been done to manage PAD, especially with the known effects of racial disparities, in how patients are cared for.

“...Nobody has really taken any real formidable steps to try to fix any of it,” she added. “That’s where I wanted to see my impact.”

Alabi believes her research can be a starting point for updating guidelines for diagnosis and care for PAD. She also believes remote monitoring could make care more accessible. Other efforts are also underway to improve awareness, detection, and treatment of PAD. That includes a PAD National Action Plan released last year by the American Heart Association, the American College of Cardiology and other organizations.

Sara Beth Stout, 41, a Savannah area mom of three children and who is not a veteran, said she struggled to get answers and care for the pain in her right leg. She knew something was terribly wrong when her right leg hurt when simply walking her kids to school a couple of blocks away from their home.

The mysterious pain started in the summer of 2019 when Stout, still in her 30s, was struck by a series of health issues — congestive heart failure, which was triggered by a virus, and a kidney stone.

The avid tap dancer was assured by her local doctors the leg pain would go away with a little time. But the throbbing pain continued every day, and it would be nearly two years before Stout would get a diagnosis, treatment, and relief from PAD,

Stout is a non-smoker and younger than the average PAD patient. In 2021, she sought care from an Emory Healthcare vascular doctor. She underwent surgery to remove a blood clot and improve blood flow in her arteries.

Almost immediately after surgery, Stout said, her leg felt better. She and her family soon went on a trip to Disney World, and she was walking 12,000 steps each day — with ease. She also started tap dancing again.

Meanwhile, Black continues to struggle with his need of a prosthetic foot and with phantom limb pain — pain in the part of the limb that is no longer there. He doesn’t understand why the disease was not caught earlier during annual checkups and why it was not detected until he was at the point of experiencing serious complications.

“I don’t know what happened to me but there needs to be changes — doctors need to notice the symptoms and finally recognize what is really going on,” he said,

What you need to know PAD

— Symptoms include painful muscle cramps in thighs or calves during exercise, climbing stairs, or walking short distances. As many as half of PAD sufferers don’t experience symptoms. Symptoms may not be obvious, even to doctors.

— Smoking is the main risk factor for PAD, according to the American College of Cardiology. Other risk factors include older age. diabetes, high blood cholesterol, high blood pressure, heart disease and stroke.

— PAD life expectancy can be difficult to determine but one in five people with PAD will suffer a heart attack, stroke or death within five years, if untreated.

— A person with PAD has a higher risk of coronary artery disease, heart attack, stroke or a transient ischemic attack (mini-stroke) than someone without peripheral artery disease.