Looks can be deceiving. You may think a clinic looks legitimate and the staff may look qualified with many “credentials” advertised — but just because someone in a pretty office is ready to take your money, it doesn’t mean they are qualified to perform real medical procedures.

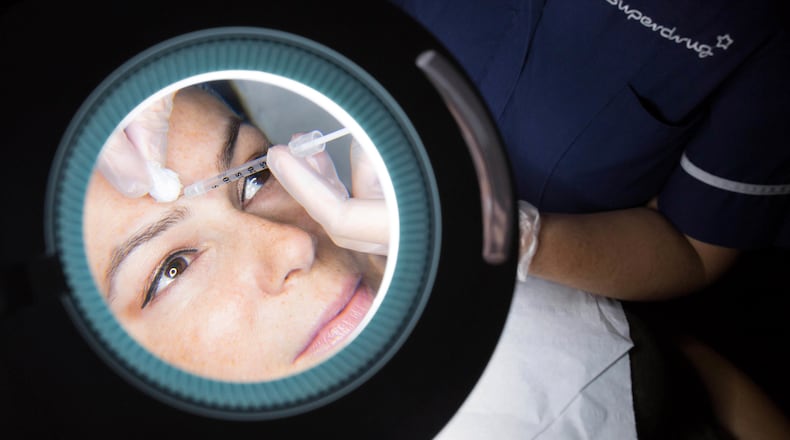

Thanks to scientific advancements in skin care and plastic surgery, a broad array of medical treatments are increasingly available to help people address common cosmetic concerns. People can now easily find neurotoxin injections — like Botox and Dysport — that temporarily reduce wrinkles; dermal fillers that add volume; and lasers treatments for sun-damaged skin. And it can be done without surgery or much downtime.

Traditionally offered at plastic surgery and dermatology offices, these nonsurgical aesthetic procedures are increasingly being offered at med spas, a $17-billion industry according to the American Med Spa Association.

However, not every med spa is created equally. Aspiring fitness influencer Bea Amma, who advocates for body positivity, went viral earlier this year after experiencing a life-threatening, flesh-eating infection from vitamin B12 and “fat dissolving” shots at a Los Angeles med spa. This type of infection could result from contaminated vials or unsanitary practices. Her $800 injections resulted in more than two years of antibiotic treatments, multiple surgeries, and $2 million in medical debt.

And she’s not alone: Professional and regulatory bodies are increasingly fielding questions and concerns about what safe and legal care should look like at a med spa.

What is a med spa?

In Georgia, a broad range of businesses fall under the med spa umbrella. These include stand-alone “bars” that offer vitamin therapy and intravenous hydration drips, Botox and aesthetic studios, and skin health and wellness clinics.

“A med spa is by definition a medical practice — not a spa,” says Amy Anderson, MBA, a practice management consultant and co-founder of BrinsonAnderson Consulting.

The “med” in med spa matters. It means there should be a medical director, qualified clinicians to counsel you, and safety protocols in place.

How can you know if med spa clinicians are qualified?

“You need to know what people have been trained in specifically,” says Dr. Melinda Haws, a board-certified plastic surgeon in Nashville and immediate past president of the Aesthetic Society. The Aesthetic Society is the professional society for board-certified plastic surgeons that is dedicated to aesthetic plastic surgery and cosmetic medicine of the face and body. “And you need to know that they know what to do if something bad happens.”

Credit: AP

Credit: AP

In Georgia, all clinicians are required to wear an identifier with their name and license when providing health care services. Look at the name tag of every person you meet in a new practice. This is an easy way to check their credentials, or the letters that come after their name. These letters will correspond to the type of license and certifications they hold and can tell you a lot about their training and scope of practice, what they are legally allowed to do in our state.

Here’s what to look for:

- The person you see for consultation and treatment planning: This should be a physician (MD or DO), nurse practitioner (NP), or physician assistant (PA).

- The medical director: The med spa needs a physician medical director “who is overseeing the treatment plans, who has put protocols in place, and — very importantly — who can help manage complications,” says Anderson.

- The person who actually performs your treatment: This can be a registered nurse (RN) only if they have an “individualized treatment plan” order from a physician, NP, or PA. Or it can be a NP, PA, or physician. Additionally, certain types of treatments require certain licenses, and certain clinicians are required to hold a Cosmetic Laser Practitioner license to perform laser treatments in Georgia.

Georgia maintains databases that can tell you if a clinician’s license is in “good standing” with the state. You can look up nurses and nurse practitioners using the Georgia Board of Nursing online license verification tool. Search physicians and physician assistants through the Georgia Composite Medical Board.

“Certified” does not always mean “qualified”

In addition to basic credentials, med spas might tout the specialized “certifications” of their clinicians. However, a certification can refer to many things, and identifying legitimate certifications can be challenging.

For instance, physicians should be certified by one of the American Board of Medical Specialties.

You have a right to ask your clinician what their credentials mean and how their training specifically prepared them to counsel you or perform your treatments. Always question titles such as “advanced master injector” or claims of being certified in specific procedures.

Consultations — not negotiations

A consultation needs to happen first — before any treatments at a med spa. A consultation refers to the initial discussion about your concerns and potential treatment options. During the consultation, you should meet with a qualified clinician: MD, DO, NP, or PA. You should expect them to review your medical history, medications, lifestyle, and health goals. They should ask about your concerns and counsel you on your treatment options. These options should include any appropriate services beyond what is offered at that clinic, as well as the risks, benefits, and expectations of each.

Credit: AP

Credit: AP

According to Haws, the consultation “should not feel transactional, not just a money exchange for product — it’s a relationship.”

Clinics might require you to sign “informed” consent documents as part of your check-in process before you even arrive for your first appointment. A prudent clinician would never ask you to sign a consent to treatment before having a discussion with you around what your concerns are.

“It shouldn’t be high pressure,” Haws says. “You should feel free to walk away and come back and get your treatment later.”

In fact, adds Anderson, a sign of an ethical clinician is that they tell you “no” from time to time.

Also they should ask about lifestyle factors or a medical history that would make your chosen treatment inappropriate.

“If they’re not asking questions about your medical history, run,” emphasizes Anderson. If, for example, you are seeking treatment to address severely sun-damaged skin, the clinician should ask about your time outdoors and sunscreen use. If you’re someone who’s always outdoors, and never wears sunscreen, and won’t agree to stay out of the sun or wear sunscreen post-treatment, the clinician should not agree to perform the treatment

Bogus clinics and bad actors

The treatments offered at med spas are, by definition, not medically necessary. As a result, insurance plans do not cover med spa services, and people pay out of pocket. Without insurance oversight, there is little regulation and few formal checks on billing or safety. Lack of regulation often gives rise to predatory practices.

Clinics may use unregulated or counterfeit drugs or devices. These include clinics that offer unapproved fat-dissolving injections like “lipodissolve,” that the FDA warns can cause serious harm. Many also do not have a medical director or they employ staff that are unqualified or unlicensed.

In some instances, qualified, licensed people own and operate clinics, but engage in profiteering. They might not explore your concerns during the consultation or fail to review risks, benefits, and alternative options.

How can you spot a bad clinic?

- If the person who counsels or treats you does not know who the medical director is, it could indicate they don’t have one. “This would be a big warning sign,” says Haws.

- If they are the only place that offers a particular treatment, it might be a bogus treatment. “With the industry being as big as it is,” says Haws. “with there being over 30,000 injectors in the country, there isn’t just one clinic who is the only place doing anything.”

- A price much lower than competitors’ prices can indicate a fake or watered-down product. “Most injectables are pretty commoditized at this point,” says Anderson, “meaning we’re going to see pretty consistent pricing across locations. “If you see Botox normally going for $12 a unit and you find it someplace for $8 a unit, something’s probably off.”

Counterfeit drugs like fake “Botox” can pose serious health risks, such as the risk of botulism, a life-threatening toxin that can cause paralysis and difficulty breathing.

“You need to ask where the product comes from and what product you are getting,” advises Haws.

Growing concern among regulators

Georgia regulators are recognizing the need to act. The Georgia Board of Nursing, the Georgia Composite Medical Board, and the Georgia Board of Pharmacy are collaborating to enhance public safety measures.

Natara Taylor, RN, Executive Director of the Georgia Board of Nursing, wrote in a statement for this article that, “as the prevalence of ‘Botox’ and IV Drip Bar businesses grows, the Georgia Board of Nursing has conducted thorough research on the scope of practice for LPNs and RNs in dermatologic aesthetic and IV hydration procedures and has issued position statements regarding these practices.”

While the position statements are intended to guide nurses practicing in this space, patients can also use them to verify if a nurse has the right credentials to deliver their care.

Safety protocols for all

While cosmetic Botox injections (unless counterfeit) are not likely to cause serious harm, even in the most unqualified of hands, dermal filler injections used to add volume and enhance facial features carry rare but real risks of blindness and skin death, and vitamin IV therapy treatments can kill you.

“You need to know that your clinician knows the risks and knows how to treat them and that they know what to do if something bad happens,” says Haws.

Ask your clinician what happens if something goes wrong during treatment. Ask them who to call and what to do if you experience a bad reaction after you leave the clinic.

If you’re getting dermal filler injections, for instance, you need to know if the clinic has hyaluronidase, on hand in case of emergency. It is used to dissolve hyaluronic acid, which is the most commonly used type of dermal filler.

“The clinic has to have hyaluronidase on premises, and more than one vial, because you can reverse everything but blindness with that,” says Haws, “If the clinician looks at you like a deer in headlights when you ask about hyaluronidase, or if they have no idea what you’re talking about, you should leave.”

Most importantly, listen to your gut, says Anderson, “If something seems off, it probably is. So get out.”

Chelsea O. P. Hagopian is a registered nurse and ANCC board-certified adult-gerontology acute care nurse practitioner with a clinical practice focus in plastic and reconstructive surgery. She is an assistant clinical professor at the Emory University Nell Hodgson Woodruff School of Nursing and executive director of the Georgia Nursing Workforce Center.

About the Author

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured