Walking down the street with Haroun Shahid Wakil was an act of community service, said his friends.

Once, while patrolling Joseph Lowery Boulevard in the West End with longtime friend Rashad Richey, Wakil spotted a teenage boy on the corner. “He said, ‘Didn’t I tell you not to be on this block selling drugs?’” Richey said. “The kid said, ‘You ain’t my daddy.’”

Wakil, 6 feet, 10 inches and at least 400 pounds, then picked the youngster up, flipped him upside down, and when the drugs flopped out of his pockets onto the street, Wakil stomped on them with his size 20 shoes.

“He said, ‘That will happen to you every time I see you selling drugs on this corner,’” said Richey, a local radio host and journalist. “I saw Haroun develop as a man and a mentor and that development came from this authentic need for others to understand there was a better way of doing things.”

Wakil, 40, was found unresponsive late Wednesday at his home in Bankhead. The cause of death was probable heart disease, according to the Fulton County Medical Examiner’s Office, though he also suffered from other health conditions and had survived a recent COVID-19 infection.

Friends said the loss has left a void among the countless people who viewed him as a brother, a protector and a tireless advocate for their communities.

“He was a gentle soul, a fearless activist and a servant leader to his community,” said Abdullah Jaber, executive director of the Georgia chapter of CAIR, the largest Islamic civil liberties and advocacy group in the country. “He didn’t fear any man. He was known only to fear his creator.”

Growing up on the South Side of Chicago, Wakil, then known as Aaron Bridges, attended the all-male Leo Catholic High School. As a young man, he was attracted to the Gangster Disciples, a street gang founded by Larry Hoover, who has been imprisoned for nearly 50 years. Around 1980, the year Wakil was born, Hoover underwent a transformation and announced the organization was shifting from violent crimes to building community and political power.

After moving to Cobb County with his mother, Wakil would have his own awakening. A 2003 arrest for marijuana would earn him jail time and probation, according to public records. During that time, Wakil experienced personal challenges, including the loss of friends and family members, said Richard Pellegrino, director of the Cobb Immigration Alliance. Wakil found solace in the Islamic faith and he began to rethink his life purpose.

“When Haroun decided to make a hard shift to become a community advocate, he completely changed everything,” Richey said. “Even (before) ... he believed in fighting the good fight even if he was confused about the fight. He never liked bullies.”

Wakil, who supported himself primarily by selling oils, shea butter, soaps and incense, founded Street Groomers, a community organization focused on patrolling, engaging, educating and assessing Black communities in and beyond metro Atlanta.

In the past month, Wakil made weekly car trips with Street Groomers, driving around the city to deliver food to about 500 homeless or hungry people, said the organization’s vice president Marcus Gray, who has known Wakil for about a decade since meeting as Little League baseball coaches in the West End.

When he spotted children cutting school, Wakil turned into a truancy officer, threatening to follow them daily to and from school to make sure they were attending. He went toe-to-toe with developers, telling them it was OK for them to make money, but not by trampling on people in the community.

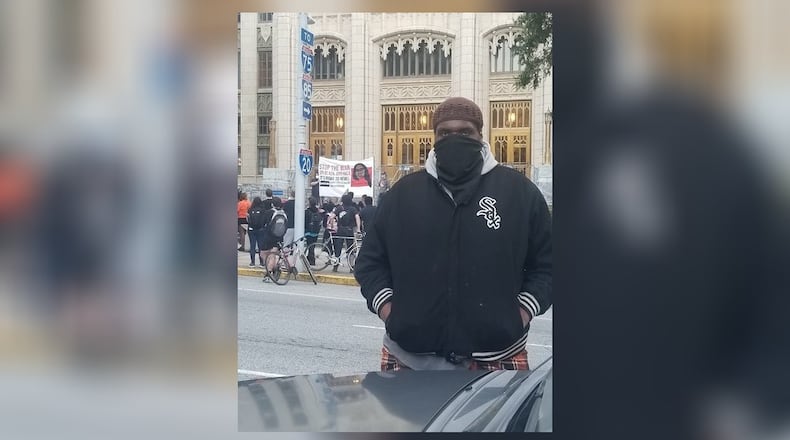

Wakil was an imposing presence at protests, rallies for racial justice and at City Council meetings, where he was known to inject humor into his fiery speech. He knew how to be aggressive and how to lighten the moment while still getting his point across, said his friends.

“Even if he didn’t see eye to eye with everyone, it would never break up a relationship,” said George Chidi, Wakil’s friend and fellow activist. “He wasn’t a guy going out and smashing windows. He was the guy trying to keep other people from smashing windows without seeming like he was making a concession by doing so.”

Years ago, Pellegrino watched Wakil when Black Lives Matter protesters met at Smyrna Town Hall to protest the fatal 2015 shooting of Nicholas Thomas by Smyrna police. “When all hell broke loose ... Haroun’s voice could be heard above everyone else’s,” Pellegrino said. “I saw both sides of him, a great defender and strong man standing up for people but also his softer side as he reached out in compassion even to the police.” Wakil somehow managed to be intimidating and endearing all at once.

Around New Year’s Eve, friends said, he was hospitalized and placed on a ventilator, but recently he had seemed to be in better health. Friends grew concerned on Wednesday when Wakil did not respond to phone calls and did not post anything new on social media. “That’s something that Haroun doesn’t do,” Gray said.

Even as his friends make plans to honor him with proclamations and pledge to continue his work, they do so with the understanding that he can never be replaced.

“He is the glue,” said Peter Brown, a member of Street Groomers. “This was him and his mission and we aligned ourselves around him. We are going to endeavor to keep his mission going, but attempting to think you are going to fill his shoes is not even a consideration.”

About the Author

The Latest

Featured