As a young federal prosecutor in the 1990s, Rod J. Rosenstein played a key role in the highly charged independent investigation of the President Bill Clinton and Hillary Clinton, over their investments in a failed real estate company known as Whitewater.

Rosenstein now is poised to take over another sensitive investigation: the FBI counterintelligence inquiry into whether President Donald Trump's current or former aides colluded with Russian intelligence to interfere with last year's election.

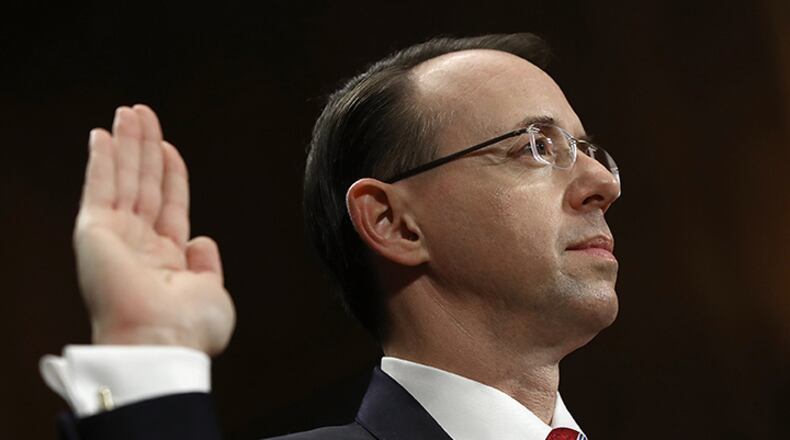

The Senate is expected to confirm Rosenstein as deputy attorney general, the No. 2 position in the Justice Department, after clearing a procedural vote Monday night with bipartisan support. The final vote is expected on Wednesday.

Rosenstein will decide whether to file criminal charges, to drop the case entirely, or to hand it off to an independent counsel, as the Whitewater investigation was later run by special prosecutor Kenneth W. Starr.

Rosenstein rose through the ranks

Rosenstein, who has served under Republican and Democratic presidents, will be responsible because Attorney General Jeff Sessions recused himself from the Russia investigation after news reports revealed that during his Senate confirmation hearing, he failed to disclose his own meetings with a Russian diplomat last year.

In all, Rosenstein has spent 27 years at the Department of Justice, the last 12 as U.S attorney for the District of Maryland. He rose steadily through the ranks with a reputation as a hard-edged career prosecutor uninterested in politics.

Rosenstein's by-the-numbers work stood out in the highly politicized, widely criticized Whitewater investigation, colleagues recall.

"He's a very thoughtful guy — and I wouldn't say that about everybody at the independent counsel's office," said Bruce W. Udolf, now a defense lawyer in Miami. "He's a solid guy and can be relied on to do the right thing, no matter what the politics."

Confident in ability to handle case

During his contentious Senate confirmation hearing on March 7, Rosenstein would not say whether he would appoint a special prosecutor for the Russian investigation, as some Democrats demanded.

But he expressed confidence that the Justice Department could handle even the most politically fraught case without compromising its independence. He said he wouldn't have qualms about questioning Sessions or even Trump, if the investigation led to them.

"I've done that before," said Rosenstein, who was part of the team that questioned President Bill Clinton at the White House in the Whitewater case. "I've been involved in questioning a president of the United States."

Rosenstein told lawmakers he had "no reason to doubt" the conclusion of the 17 U.S. intelligence agencies that Russia's government sought to influence the U.S. presidential race through cyberhacks of Democratic Party leaders and other operations.

His role as Sessions’ deputy

As deputy attorney general, Rosenstein will oversee day-to-day operations at the Justice Department and help carry out the conservative shift in legal priorities that Trump and Sessions have promised.

Rosenstein will lead the department's efforts to investigate more violent crime, one of his priorities as a prosecutor in Maryland.

He also will help lead efforts aimed at tougher enforcement of immigration laws, including trying to compel so-called sanctuary cities to share information on people in the country illegally and to hand over suspects for deportation.

Early life

Rosenstein grew up in a Philadelphia suburb, where his father ran a company that processed mortgage payments for banks. He attended the University of Pennsylvania and Harvard Law School, where he was editor of the Harvard Law Review. He and his wife have two teenage daughters.

A young lawyer

After law school, he served as a law clerk to Judge Douglas H. Ginsburg of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit. In 1990, he joined the Justice Department, landing a spot in the "honors program" for young lawyers that grooms future stars.

He soon joined the agency's top levels, working as a counsel for Deputy Attorney General Philip B. Heymann in Clinton's first term.

"For me, the grand hallways of Main Justice echo with the voices of mentors and friends," Rosenstein told lawmakers last month. "They taught me to ask the right questions. First, what can we do? Second, what should we do? And third, how will we explain it?"

Helped investigate the Clintons

In 1995, he joined the independent counsel investigation looking into real estate investments in Arkansas by the Clintons and several of their associates. He was part of the trial team that won convictions against Arkansas Gov. Jim Guy Tucker and two others. The Clintons were never charged.

Rosenstein later led an investigation into whether the Clinton administration had improperly obtained FBI background reports, and questioned Hillary Clinton at the White House in January 1998. No one was charged in that case.

Rosenstein left the special prosecutor's office before it veered into the extramarital affair between President Clinton and White House intern Monica S. Lewinsky. That investigation ultimately led to a House vote to impeach Clinton in 1998, although he later was acquitted in the Senate.

Nominated and confirmed under George W. Bush

After working several years as a federal prosecutor in Maryland, Rosenstein ran the Justice Department's tax division. In May 2005, President George W. Bush nominated him to be U.S. attorney in Maryland, and he was unanimously confirmed by the Senate.

When he arrived in Baltimore, the office was just beginning Project Exile, a program his predecessor planned to attack violent crime. In the first year, the program looked like a flop because the violent crime rate didn't budge, said Steve Levin, one of Rosenstein's top deputies at the time.

"It would have been very easy for Rod to end the program and blame it on a predecessor and say, 'Let's try something else,'" said Levin. "He was willing to take any hits he was getting. He wasn't concerned about himself. He was concerned with the office."

Reappointed to U.S. attorney by Obama

In November 2007, Bush nominated Rosenstein to a seat on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 4th Circuit. But the Democratic-controlled Senate refused to schedule a hearing and the nomination lapsed. Obama then reappointed him to the U.S. attorney's job.

Stood by law enforcement, fought corruption

As a federal prosecutor, supporters say, Rosenstein forged close relationships with local law enforcement, devoting resources to gritty drug and gun cases and standing with police chiefs at raucous community meetings.

He also handled some notable public corruption cases, including a bribery case that sent a powerful county executive to jail for seven years.

'He's seen it all, nothing surprises him'

Rosenstein's office chose not to file charges in the case of Freddy Gray, whose death from injuries in police custody sparked riots in Baltimore in 2015. But he filed racketeering charges last month against seven Baltimore police officers in another case.

"He's seen it all, so nothing surprises him," said Baltimore Police Commissioner Kevin Davis, who has watched Rosenstein's work closely over the years. He said he was impressed with Rosenstein's collegiality and willingness to hash out strategy on complex investigations.

"When you get to that level of leadership, you know that every day can be your last day on the job," Davis said. "He'll be able to sleep eight hours a night. He's going to make decisions in the right interests of justice."

About the Author

The Latest

Featured