Five victims, countless memories

One wanted to help children. Another set her sights on foreign mission service. Yet another would follow the lead set by her aunt.

Those dreams, like their lives, have come to a sudden end. Five nursing students from Georgia Southern University were killed Wednesday morning in a pre-dawn accident.

Friends and classmates who’d entered Georgia Southern’s nursing school the beginning of this school year, they were victims of a chain-reaction crash on Interstate 16 not far from Savannah. A state trooper witness to the carnage called it the worst accident he’d ever seen.

Perhaps the worst thing ever to happen at Georgia Southern, too. The names of the five are forever inscribed in memorials and etched in memories: Caitlyn Baggett of Millen, Catherine “McKay” Pittman of Alpharetta, Emily Clark of Powder Springs, Morgan Bass of Leesburg and Abbie Deloach of Savannah — each a junior, each surely intending to make her own way in life after getting a nursing degree next year.

On the day of their deaths, the five were en route to a Savannah hospital for hands-on clinical training, their last session of the semester. Two others were injured.

Two were buried Saturday; two are to be interred Sunday; the last, on Monday.

Yet sorrowful gatherings under funeral-home tents don’t end these young women’s stories. In a series of interviews and from other sources, The Atlanta Journal-Constitution has created brief portraits of the five.

Perhaps the best epitaph for them came from Sharon Radzyminski, the nursing school’s chairwoman:

“They were – How do I put this? – they were fun,” she said Friday. “They were just a delight.”

Such a delight that they will be recalled by their first names.

Caitlyn? She might have been a small-town girl, but she had a big-time way with words.

“She told you like it was,” her uncle, Stewart Hooks, said Friday. “She wouldn’t hold her tongue.”

Nor did she curtail her dreams. Caitlyn transferred from East Georgia State College to enroll at Georgia Southern. Some newcomers may have been intimidated by strange faces, but not her.

The girl, said her uncle, also had a way to get a conversation going. Call it spunk.

“If there was a group and no one would say anything, count on Caitlyn” to end the silence, he said.

In a teary ceremony at Georgia Southern Thursday night, an unnamed nursing student echoed Caitlyn’s uncle. The Millen resident, the student said, was outspoken – even in her texts.

On Friday, as her family dealt with arranging a funeral no one anticipated, Caitlyn’s uncle shared a memory. On Wednesday, relatives started calling each other, saying they needed to come together, quick. Something awful had happened.

“You see everybody going through stuff like that, and you never think it could happen to you,” Hooks said. “You’re not prepared for it.”

Talk about prepared: Catherine — everyone called her “McKay” — was happily preparing for a life helping others.

“She wanted to do everything,” said friend and fellow student Becca Reynolds. “She wanted to go on mission trips with her nursing, help disadvantaged people, sick children. She had the biggest heart, and she wanted to help everyone she could.”

The two had been best friends since their freshman year. That bond grew even stronger after each pledged Alpha Delta Chi, a Christian sorority. McKay was the president; her friend was president-elect, scheduled to take over in just days.

McKay also was active in Southern Ambassadors. Student volunteers, clad in Georgia Southern’s blue, conduct campus tours for prospective students and their parents. Katy Beth Lockwood, her adviser in the group, remembered that McKay’s first steps were a little shaky — literally.

McKay, said Lockwood, learned the toughest part of the task: walking backward while talking to visitors. It’s hard to do and still look graceful. “But she learned to do it.”

She was a conscientious daughter, too. Sherrin Pittman had learned to expect a daily morning call from her girl at Georgia Southern. Wednesday morning, she told Channel 2 Action News, that call didn’t come.

Reynolds, her friend and sorority sister, said the two had had candid conversations about heaven. Were there really pearly gates? Would horses be there?

“You know now, McKay,” she said, “if there are horses.”

Neil Hollis knew something about Emily. “She was the one I was going to marry,” he said Thursday.

They met in October 2013, and Hollis was wowed: She sure was pretty! He didn’t see her again for several months, but the wonders of social media changed that.

On Valentine’s Day 2014, the two connected over Snapchat. Later that night, they had an informal date, eating popcorn and watching “Frozen.” Emily, he learned, wanted to follow in the footsteps of a cherished aunt and become a nurse. He liked what he heard, what he saw. The two, each studying at Georgia Southern, soon became an item.

“She was beautiful in every single way,” Hollis said Thursday. “Her smile was contagious to anyone who saw it. She was perfect to me.”

On Tuesday night, he asked Emily to let him know when she arrived in Savannah for her clinical work the next day. He recalled his last words to her.

“I love you, Emily. Please let me know when you get there.”

Morgan arrived early — two months early, in fact. When she was born, the child who would become a nursing student weighed 2 pounds, 4 ounces. But she was healthy. She was perfect. Her mother, Mary Helen Mehaffey, was delighted.

“I just knew she was here for a reason,” her mother said Saturday.

She grew, and not just in stature. Morgan’s tastes evolved as she did. By the time she entered Georgia Southern, Morgan was a fashionista, a walking statement of what’s au courant. She had a keen sense of design and color, too. Morgan refinished and painted the furniture she took to Statesboro. Needed something painted? Call her.

“She was really creative,” Mehaffey said. “She could’ve done just about anything.”

That included communications. At least one professor, impressed with her writing talents, urged her to consider other careers — journalism, perhaps. Morgan wouldn’t have it. She would be a nurse anesthetist.

In a perfect world, she’d have worked with babies, entering life small and helpless. As she had been.

Then there was Abbie. She shone as brightly as the candles held by thousands at Thursday’s memorial. Christie Whittington knew.

“She was stellar,” Whittington said Saturday.

She met Abbie through Connection Church, a nondenominational congregation in Statesboro. Abbie and her boyfriend, she said, were serious about each other, serious about living good lives. They sought her advice, as well as that of her husband, Cody Whittington, a pastor at the church.

“She was asking how to live a godly life, how to please God,” she said. “You’d expect a 21-year-old college student to live it up, drinking her college years away. She really had a lot figured out.”

Abbie was unique, said her friend Allison Jackson. She spoke about Abbie at Thursday’s vigil, holding a candle in the evening breeze.

She attended Abbie’s funeral Saturday. For the moment, Jackson seemed empty of tears. “I’d rather talk about the enjoyable moments I had with her rather than cry,” she said.

As news of the wreck spread on Wednesday, she said, a lot of students did what came natural: they went to class. But they laid aside lessons on medical procedures for some healing that comes only with time, and tears, and shared memories.

They talked about their lost classmates, their losses: Caitlyn, McKay, Emily, Morgan, Abbie.

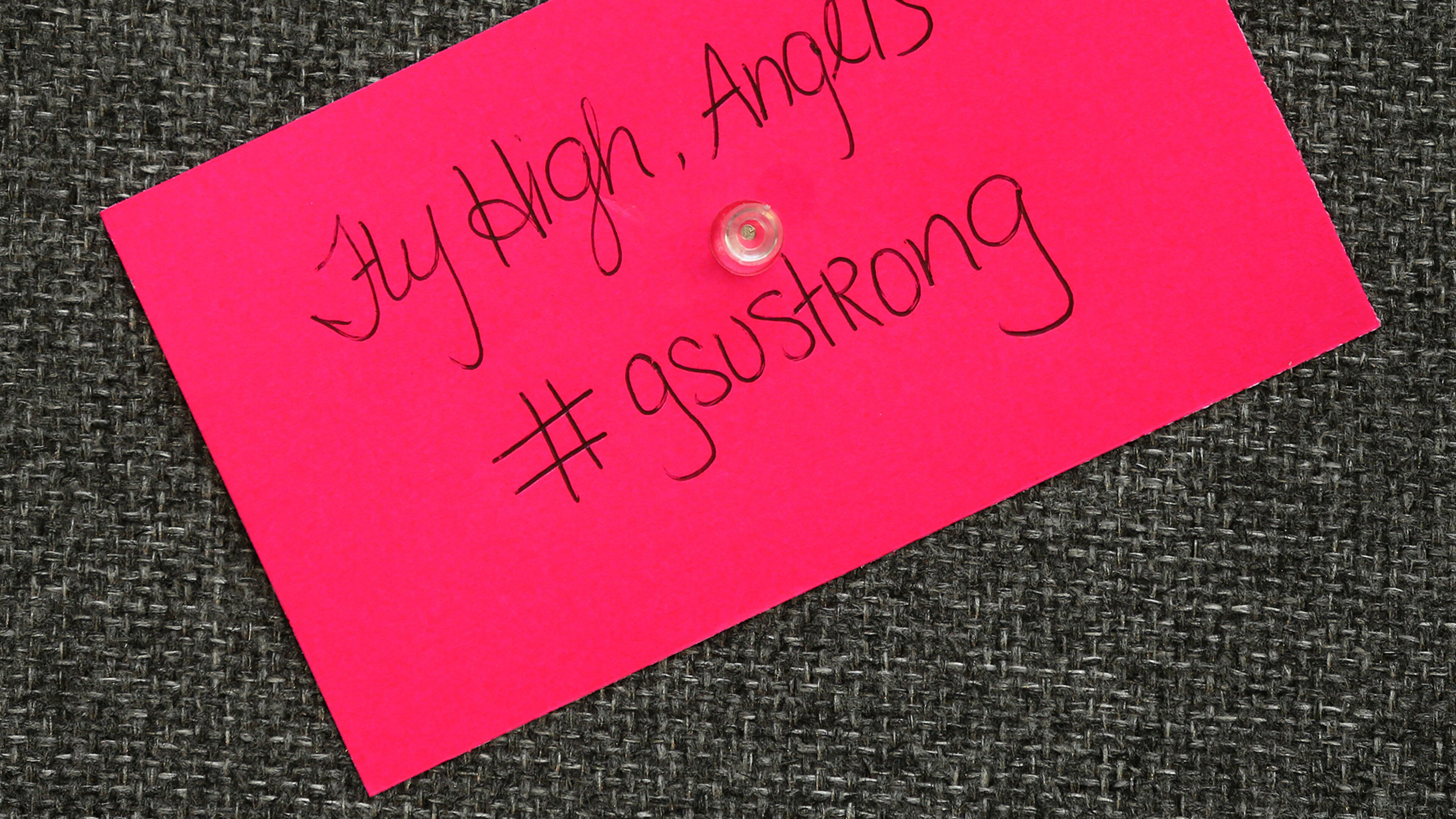

The five are recalled, too, on twin wreaths posted at the main gates of Georgia Southern. At week’s end, they were still fresh, white petals dappled with morning dew, blue ribbons shiny in the sun.

They are no longer at school, those young women, but that hardly means they are gone. A part of them will remain in the sorority sisters who go on to greater things in life; in future nurses who’ll minister to the ill; and in anyone who shared their dreams.