NEW YORK (AP) — Images of Althea Gibson are everywhere at the U.S. Open, 75 years since she became the first Black player at a major tennis tournament.

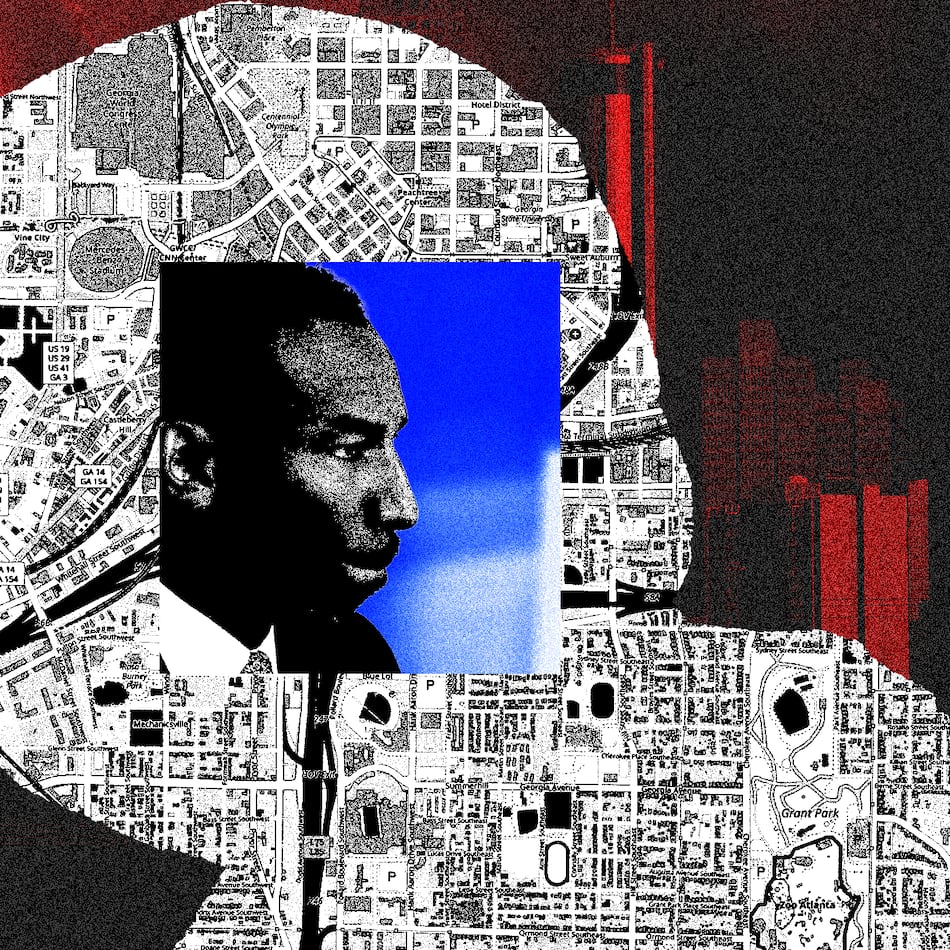

The American Grand Slam event's logo is multilayered artwork of her face in profile. Clips of Gibson flash across screens inside Arthur Ashe Stadium. A tribute narrated by Venus Williams is part of the soundtrack during breaks.

“The most important part is that we are celebrating it and recognizing it because Althea accomplished so much," Williams said. “A lot of it has not been given the credit it deserves and the attention and the praise.”

While Gibson has been memorialized with a statue at the Flushing Meadows site since 2019, she is now at the forefront of the U.S. Open, with signs reading, “Celebrating 75 years of breaking barriers" and two weeks built around honoring her story, a complicated and difficult one without a happy ending.

"Personally, I feel like everybody’s waited too long to really celebrate her," Billie Jean King told The Associated Press. “She was the first, and when you’re the first, you should be celebrated the most."

Making it tough for Althea Gibson

Gibson fought with the U.S. Lawn Tennis Association just to get admitted in 1950 to what was then called the U.S. Nationals. It took a public letter from prominent white player Alice Marble to make it happen, and even then it wasn't easy.

“(Organizers) put her on a very back court, No. 14. Hard to get to. The area for people to watch was tiny. And they changed the rules and sent photographers to take pictures of her match, which was never allowed for other people,” said Sally Jacobs, author of “Althea: The Life of Tennis Champion Althea Gibson.”

"Of course many people thought, ‘Well, this could distract her, this could cause commotion.’ This was to bring down her game. They really were making it tough for her.”

Gibson beat Barbara Knapp, anyway, before losing to three-time reigning Wimbledon champion Louise Brough. Even as Gibson won Grand Slam titles — what's now the French Open in 1956, along with the U.S. Nationals and Wimbledon in 1957 and '58 — success did not open doors.

“She grew up in the South and it was the Jim Crow era, so she spent most of her time out of the country playing,” former player-turned-executive Katrina Adams said. “I can’t imagine her trying to compete in America in the ’50s and ’60s and not being treated as a normal human being, not being able to walk into the front door of these clubs and stadiums and being treated the way that she was, but still rising to the occasion and being the champion that she was.”

Althea Gibson was pushed to the margins

Gibson played before the professional era, so even the top tournaments had no prize money. As a result, many of her accomplishments have been lost to time, and she wound up quitting to play golf, sing and act.

She broke golf's color barrier, too, released a jazz album, appeared in a movie with John Wayne and performed on “The Ed Sullivan Show” twice. Yet she's far less known compared to other pioneers of the time.

“Her story has been pushed in many ways to the margins,” National Women's History Museum president and CEO Frédérique Irwin said. “You might think about Jackie Robinson. Everybody knows who Jackie Robinson was. Yet, does anyone, if you walk down the street, know Althea Gibson’s name?"

Michelle Curry, the administrator of her estate, said Gibson “sometimes becomes invisible” because she was not loud about her plight. King, who idolized her before the two got to know each other as adults, saw the pressure of people wanting Gibson to speak up more about social justice and observed, “She was trying to survive.”

Gibson's autobiography, released in 1958, was titled, “I Always Wanted To Be Somebody.” Zina Garrison, who reached the Wimbledon final in 1990, said Gibson “never really got her due.”

The U.S. Open is trying to right a wrong

The USTA sought input from contemporaries and members of the Black community to come up with ways to honor Gibson all these years later and more than two decades since her death. Chief diversity and inclusion officer Marisa Grimes Galiber said the goal was to make sure people understood Gibson's history.

“This was an opportunity to maybe make right what we didn’t do as good a job of celebrating Althea many years ago that we could right that wrong today,” said Nicole Kankam, USTA professional tennis marketing and entertainment managing director.

Curry wished Gibson could have seen fans lining up for photos with the tournament logo — designed by artist Melissa Koby, the first Black woman responsible for the U.S. Open's feature art — and figured she'd be thankful, mixed with the thought: "I don’t know what took you guys so long.”

A luncheon in Gibson's honor took place Sunday, after which three Black women performed the opening night anthem. The band from Florida A&M — the school Gibson attended — is set to play Wednesday night when the U.S. Open celebrates historically Black colleges and universities.

One other tribute to Gibson's legacy was more organic: Black tennis players such as Williams and Francis Tiafoe were on court Monday, and Coco Gauff is on Tuesday's schedule.

___

More AP tennis: https://apnews.com/hub/tennis

The Latest

Featured