Crayons, chess, freedom: Inmates face past, chart new path in Georgia jail

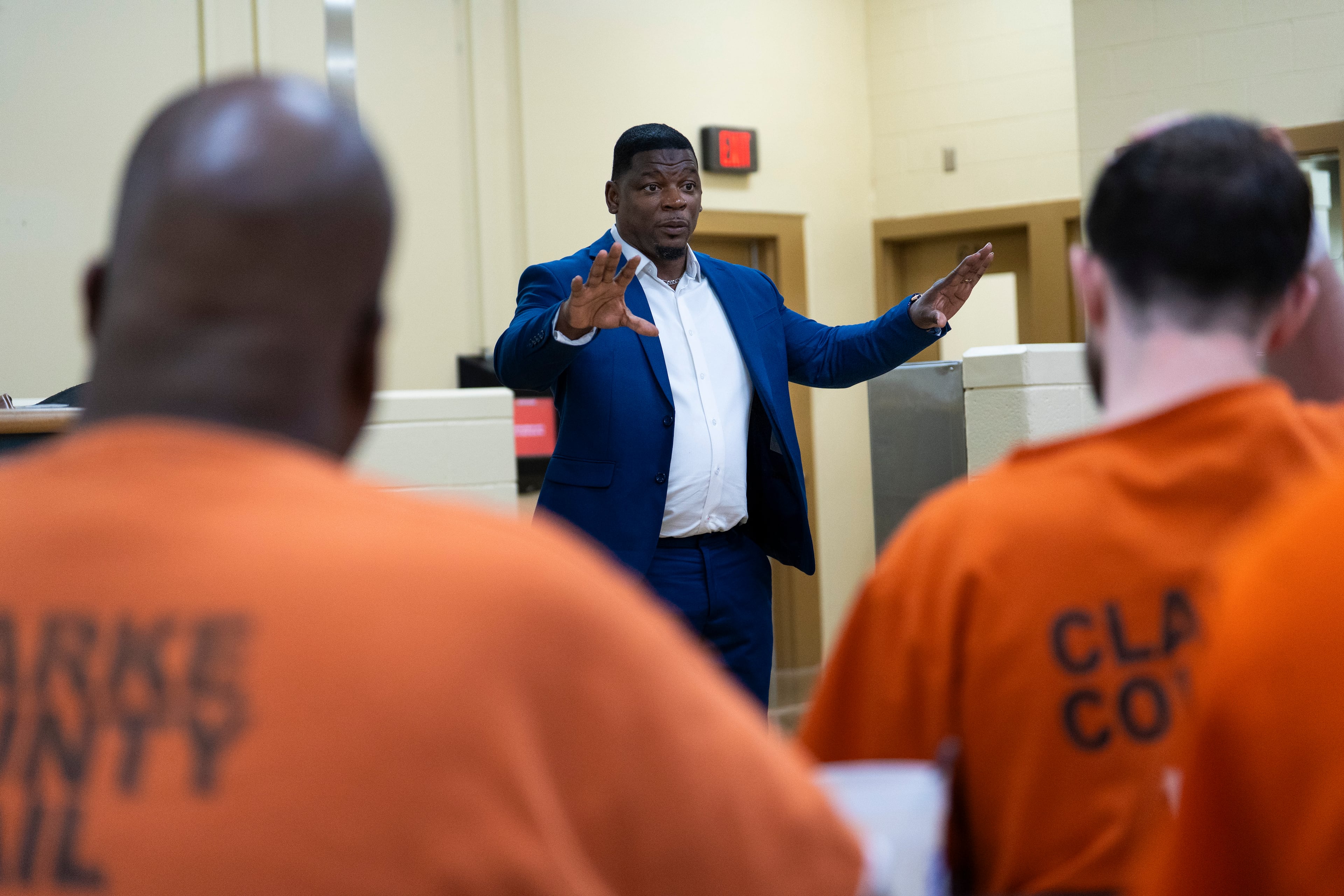

ATHENS — Seventeen men in orange uniforms sit scattered around cold, metal tables, all eyes on the man at the front.

Shane Sims doesn’t raise his voice. They listen.

“My goal,” he says, “is not to change who you are, but to give you tools to restructure what you are.”

For a moment, the jail fades. The room feels less like punishment and more like a threshold.

Sims paces slowly, his voice rising not in volume but in conviction.

“This class,” he says, “doesn’t deny human characteristics. It says you need principles to guide it the right way.”

Most lean in, not because they have to but because he knows their pain.

Decades ago, Sims sat where they sit — wearing the same uniform, eating the same food, feeling the same dread, sentenced to life.

Now free, he is back to light a path out. For eight weeks, they will walk it with him.

The program

Athens-Clarke County Jail has embarked this year on a bold experiment aimed at making it less likely inmates will return after they’re set free.

Inmates are chosen to participate in daily classes on topics such as conflict resolution, fatherhood, addiction and art. Sims, a 47-year-old former convicted felon, helped design the program, anchored by his “Principles Over Passion” course.

The Re-Entry Success Jail Resident Program is much more than organized instruction, though.

The men live apart from the general population without an officer watching them around the clock. They sleep in a large common space instead of smaller cells and hold each other accountable while managing their daily routines.

They range in age from 22 to 55. Most are awaiting trial or sentencing hearings, with charges that include aggravated assault, burglary, intent to commit theft and probation violations. Some have served time in state prison. All have been arrested at least once before the charges they face now.

For these men, it’s a chance to practice freedom before they earn it back — and to face what keeps pulling them inside.

Crayon class

Sims hands out sheets of paper and opens a box of crayons. It’s the first week. Some of the men laugh — one jokes it’s been since kindergarten since he last colored. Sims tells them to pick one crayon, no peeking for a favorite color.

“You’ve got 10 minutes,” he says. “Draw anything you value.”

Heads bend over paper. No one looks up until Sims calls time.

They talk through a few drawings. Sims gives the next instruction. “Stand up. Walk around. Add a mark to every picture — whatever you want.”

They hesitate, but they do it. When they sit back down, Sims holds up one page. Brown lines sketch trees, fields, a sun.

“Why didn’t he just draw dirt?” Sims asks. “He used brown and still drew the sun. He saw past what he inherited.”

He paces as they listen.

“We don’t choose our color — what we’re born into,” he says. Brown might mean parents with addiction. He grabs a blue crayon and scribbles over the trees. Blue is a history of molestation. He takes a green crayon and crosses over the sun. Green is anger from a home with a violent father.

“After you did your damnedest to draw the best picture you could,” Sims says, “what happened?”

He holds the crayon in the air.

“Somebody else came and marked on your picture.”

The quiz

They take the “Adverse Childhood Experiences Quiz” together in the second week. Ten questions about trauma before age 18: abuse, neglect, living with addiction or violence.

“Prepare your brain,” Sims says. “We’re going to parts of your life you haven’t visited — not consciously — in a long time.”

A score of 10 means the highest exposure to early trauma. Research shows the higher the score, the greater the risk of struggles later in life.

Most score between 4 and 6; a few hit 8 or 9.

“A person with a score of 2 or higher is more than likely to end up where we are in this room today,” Sims says. “Let that sink in.”

Nearly everyone answers yes to Did someone at home often insult, humiliate or curse at you? and Did you live with someone who had a serious drinking or drug problem?

As they unpack the results, a moment makes Sims smile. Cornelius Peterson at first scores himself a zero. His peers call him out and push him to try again.

“He didn’t want to accept it,” says Eldreco Craft. “He got mad.”

Peterson rereads the questions. This time, he admits what he’d buried.

“I think that was me still suppressing it,” he says later. “I wasn’t ready to be honest yet.”

Sims’ story

Sims describes his early childhood in 1980s East Athens as normal, until he was 12 and saw both of his parents using crack cocaine.

He says he began gravitating toward friends who were facing similar struggles at home. He started drinking alcohol, smoking marijuana and fathered a child at 14.

He robbed a store with friends, one of whom shot and killed the clerk. Sims pleaded guilty to his role and was sentenced to life in prison plus 15 years.

He says he entered prison confused, angry and carrying a sense of betrayal. Eventually, though, deputies referred to him as “Counselor Sims.”

“Because I was always talking to somebody or listening to somebody,” he says. “I was healing myself by helping others heal.”

He worked administrative orderly jobs at prisons in Telfair, Jackson and Savannah. Sims says three wardens petitioned for his release.

After 20 years, he came home.

Today, Sims is a certified addiction recovery specialist, executive director of a nonprofit and a chaplain at Athens-Clarke County Jail.

Deputy and sheriff

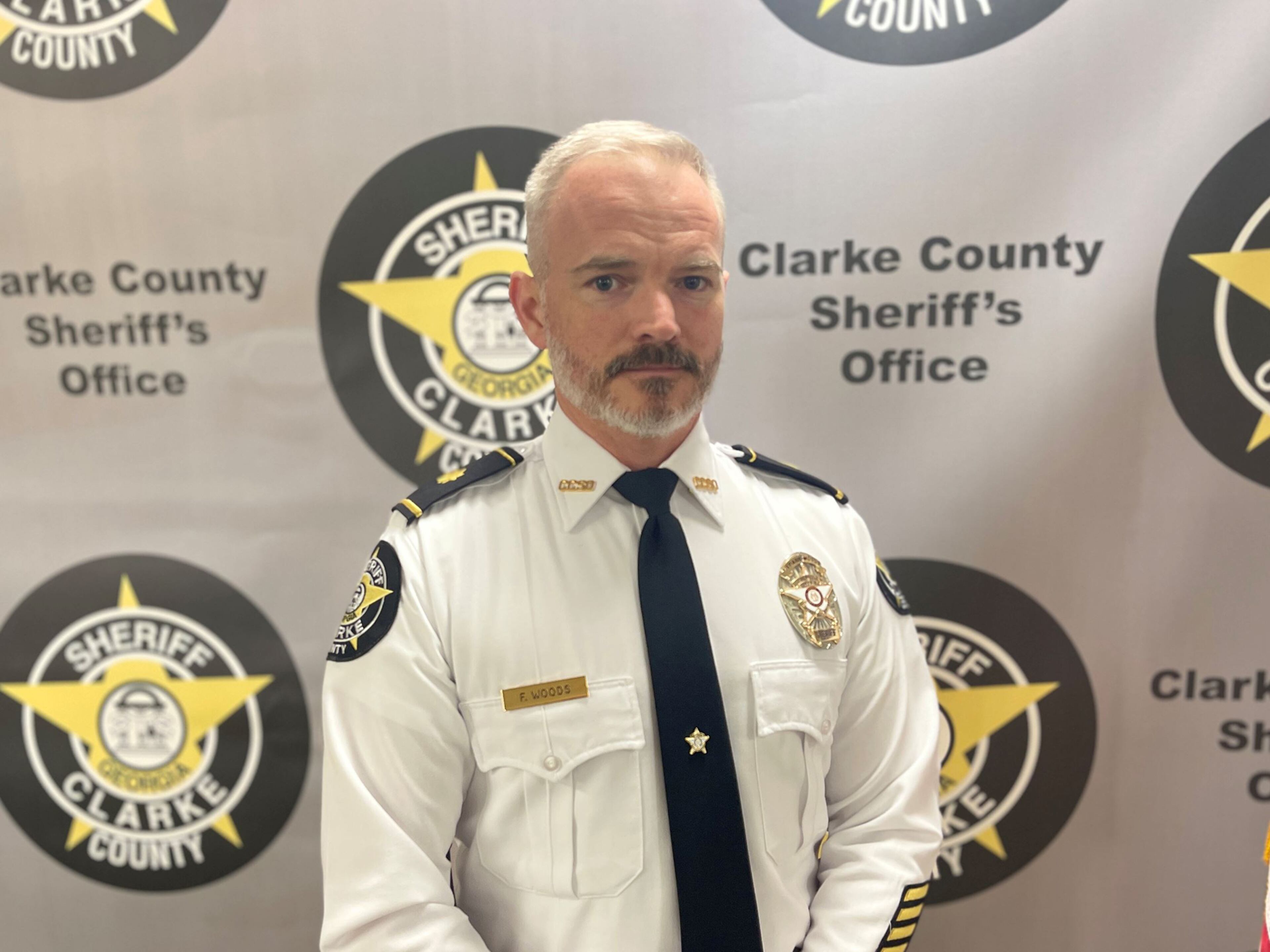

When Frank Woods became chief deputy at Athens-Clarke County Jail in 2022, he inherited a short-staffed, overburdened facility with low morale and nearly 500 inmates — many who stayed in cells almost 23 hours a day.

“I wanted something to engage people in a different way,” he says. “Shift everybody’s paradigm a little bit.”

Woods reached out to Sims, and together they launched a “Principles Over Passion” class for about 10 men. But Woods wanted more. He knew the men needed a dedicated space — somewhere safe enough to be open and vulnerable.

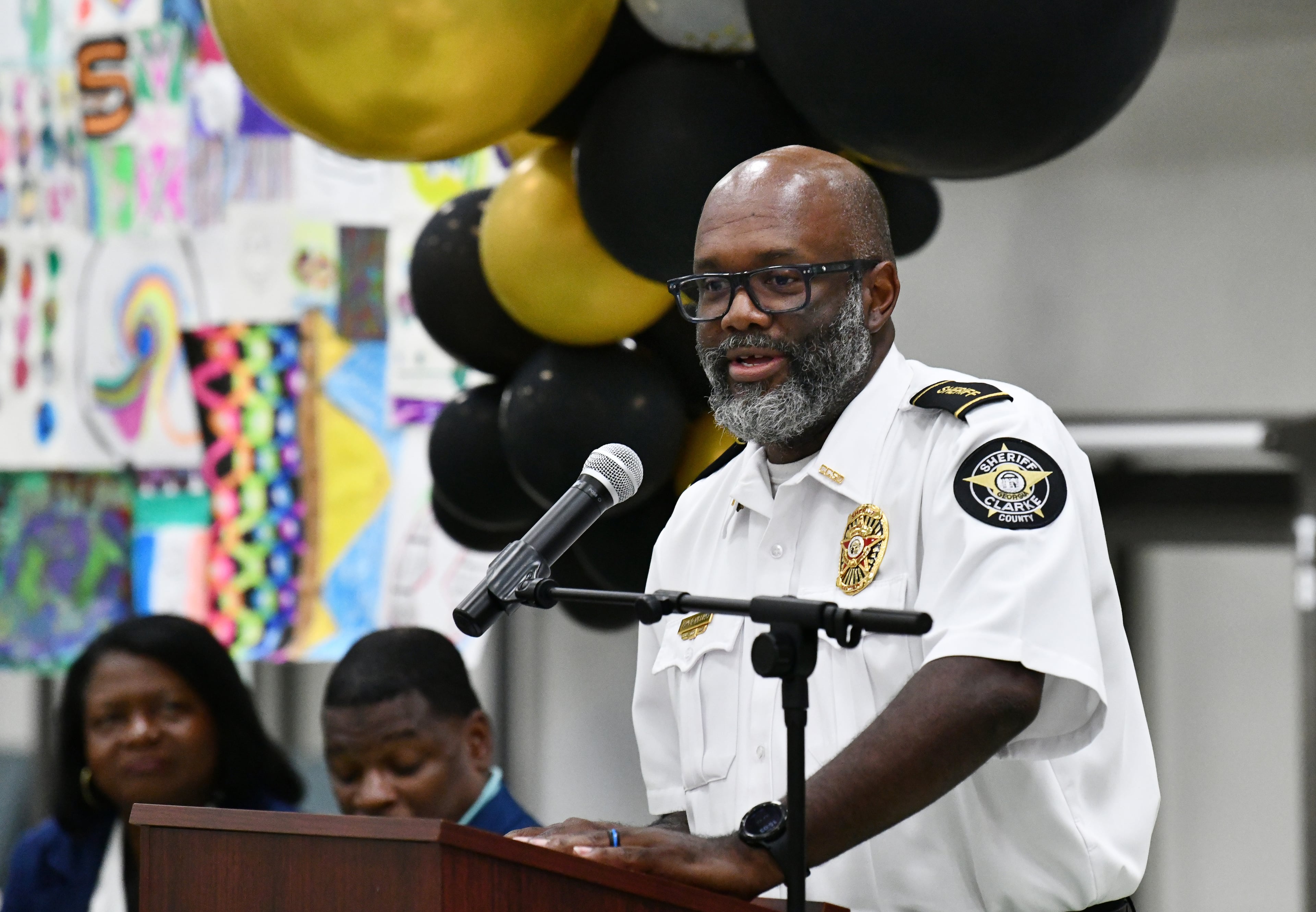

Sheriff John Q. Williams backed the idea despite skeptics.

“People asked how we could we afford to do this,” Williams says. “I responded: How can we afford not to do this?”

So Woods and Sims walked through Unit Six — then an unused, rundown block with parts of the ceiling caving in. They got to work. Now it holds an open classroom with tables, an outdoor area with a basketball hoop, a small library stocked with books and puzzles, individual showers and bathrooms, rows of bunks, and phones and kiosks tucked away in a corner for privacy.

J. Terry Norris, executive director of the Georgia Sheriffs Association, says he’s unaware of any other jails in Georgia offering this type of program.

The first eight-week cohort finished earlier this year with few problems.

The second cohort began in late April after the jail’s staff and Sims chose 17 inmates from the 65 who had applied.

The cohort has proven tougher — partly because of the men’s charges and the deeper childhood trauma many carry.

There were hiccups early on. A few men stashed unauthorized clothing. One lashed out after missing his daily medication. One inmate was removed for a psychiatric evaluation, before returning a few days later.

A few weeks into the program, though, there also are signs of progress.

“This group is exactly what I wanted,” Sims says.

Phone call

A phone call in the first month gives Brandon Williamson an early chance to test what he’s learned.

Waiting to talk to his daughter, his ex-wife reminds him he hasn’t seen his children in years.

He doesn’t snap back like he once would have. Instead, he tells her the truth: Missing them is a wound he’s learning to face.

“I kept my tone low and tried something different,” he says later. “Instead of getting bent out of shape like I normally would, I stayed calm — and it turned out to be a good conversation.”

Young and old

Sims notices 22-year-old Danrius Hendricks, the youngest inmate in the program, sitting silent, head down, lost in his thoughts. He stops mid-lesson and addresses him in front of everyone.

“Whatever’s going on in your head — if the only person you talk to is yourself, you’re going to stay trapped in that same world,” Sims says.

Peterson reaches over and rests a hand on Hendricks’ shoulder.

Later that day, Sims turns to the oldest among them, 55-year-old Kirby Kesler. He calls him Mr. Kesler, a mark of respect.

“I can see it on your face — you’re doing the work,” Sims tells him. “You look lighter today. You’re not carrying something heavy inside you.”

Hendricks’ story

Five years ago, Hendricks pictured himself playing college football.

A lanky, quick-footed receiver and defensive back, he transferred to Clarke Central High in Athens for his senior year hoping to impress recruiters. But not long after, he was arrested for the first time — there would be no college football scholarships. He drifted deeper into gang life and racked up charges: battery, drug possession.

At first, he thought Sims’ class was pointless.

“I thought this was going to be a bunch of BS,” he says.

During the first class, he sat quietly near the back, arms folded.

But he acknowledges the program has forced him to face parts of himself he’d buried behind bravado.

His father was in and out of prison, and Hendricks says their last real conversation ended with his dad asking for money. He remembers his mother coming to just one basketball game, despite years of promises to watch him play football.

A few weeks after the first class, Hendricks says he is learning to sit with feelings instead of stuffing them down. He cried in front of Sims. He realized vulnerability didn’t make him weak.

“I’m not as angry anymore,” he says. “I still have insecurities, but Shane helps me through that. Shane gives me something I wish my father had given me.”

Kesler’s story

Since the 1990s, Kesler has cycled in and out of jail and prison, each fresh start undone by old habits — drugs, alcohol, the wounds of his boyhood. His offenses included assault, trespassing and possession of narcotics.

During Sims’ first class, while Hendricks stayed in the background, Kesler sat on the edge of his seat near the front, quick to answer questions.

“It blew my mind because I had never thought about trauma,” Kesler says.

Growing up in Jackson County, he says he had an older brother who never missed a chance to knock him down. If Kesler lost a fight at school, his brother beat him again at home. In front of friends he called him stupid, until Kesler believed it himself.

He took his first drink at 15. Then marijuana. Then meth. By his 20s, he was in prison for the first time. Between stints, he laid floors for another brother’s construction business — until the bottle and drugs caught him again. Eventually, even family drew the line.

He drifted between panhandling and tent camps. Many nights, he lay awake, drunk and crying, wondering how his life had shrunk so far from what he’d imagined. His latest arrest came after an argument in camp ended with a tent set on fire.

He’s focused on rebuilding trust with family.

“They’re tired of me saying one thing and doing another,” he says. “I want to prove I can be the man I’m supposed to be.”

Chess class

Lemuel “Life” LaRoche, a longtime Athens resident who runs a nonprofit, leads a weekly class where chess becomes a lesson in conflict resolution.

To explain the board, he tells the inmates a story: Two friends fall out over a stolen pair of shoes. A confrontation. A neighborhood picks sides.

“The pawns are fighting,” LaRoche says, nudging the first pieces forward.

Tensions rise; the knights step in.

“Shooters come out,” he says, tracing L-shaped paths across the board with his finger.

When pawns and knights fall, the queens — mothers — intervene.

“Stop all this,” LaRoche says, moving the queen to block the chaos. Then come the bishops — the church leaders.

All this violence over one pair of shoes: Pawns fighting, knights shooting, mothers and ministers trying to stop it.

“But what happens?” LaRoche asks. “Everybody gets taken off the board. They end up dead — or in here. This is chess.”

Some know the game; others have never touched a piece. LaRoche challenges them to plan ahead — to win by setting goals that take dozens of moves.

He pivots again from the board to real life. The need to network. To communicate. To see consequences before they come.

“At some point, you’ll make it out of here,” he says. “What’s your next move?”

Change of address

One of the challenges in a program like this is that inmates often are moved while in custody and awaiting a trial or sentencing.

One participant is transferred to a neighboring county jail. Two others are told they could be sent to state prison any day. Others attend court hearings.

Hendricks, the youngest, bonds out five weeks into the program. Kesler, the oldest, is released from jail just days before it ends.

Most inmates, though, remain.

The cake

Everyone chips in from a recent commissary run. Honey buns, cookies, Snickers, Butterfingers, M&Ms — all tossed together to make a cake for Patrick Wilkins’ 32nd birthday.

They press honey buns into a base, smear frosting from the cookies for layers, then pile candy on top. The men gather around and sing “Happy Birthday.” There’s no candle to blow out.

“It’s the best we can do,” Wilkins says with a grin.

The letter

Several weeks into the program, Sims assigns the men a task: write a letter to the 16-year-old version of themselves.

They start with an affirmation — that they matter, that they aren’t broken. They name the trauma that shaped them, the mistakes it fueled and the resilience it built. They end with practical advice, anchored in four core principles: trustworthiness, truthfulness, honesty and integrity.

Putting it all on paper leaves many feeling raw. Brian Martin says he wishes someone had talked to him this way years ago, and doesn’t sugarcoat things when he confronts his younger self.

“Listen to the s--- I have to say, you hardheaded ass,” he says.

Donovan Mallard admits he didn’t know what to do with the old memories he’d dug up.

“I’m thinking about what I want to do, what I want to build,” he says. “But there’s so much in the past I still have to face.”

Sims tells them to read the letter again — and again — and to keep shaping the advice they gave themselves, guided by those same four principles.

“The trauma is the problem,” Sims says. “The solution is in your principles.”

And he reminds them: Read it on the bad days. Read it on the good days, too. Over time, as they add and revise, the letter becomes more than words on a page.

The mural

Greg Mouzayck presses a sponge dipped in dark purple paint against the bare cinder-block wall, then layers over it with patches of light green. He splatters orange and yellow for texture. Beside him, Mallard helps tape off crisp letters as the mural in Unit Six comes to life.

“I didn’t see it at first. I wasn’t sure it would work,” Mallard says, nodding at Mouzayck. “But he had the vision.”

When they peel back the tape, these words stretch across the wall: “Out of This World Recovery.” Planets, a satellite and a cartoon UFO beaming up a cow spin the solar system theme wider.

Each man designs his own star. The first cohort, which Mouzayck also joined, used puzzle pieces. This time, guided by a local artist in creative sessions, Mouzayck pushes himself further.

“I’m a tattoo artist on the outside,” he says, studying the finished mural. “But this showed me I can do more than I thought.”

What’s next?

As the program nears its end, Williamson and Mallard both talk about what comes next — and what scares them.

Williamson could face years behind bars, depending on the outcome of his case. Mallard expects to go to prison after a judge denied his request to enter rehab. But each man carries that uncertainty differently.

“I’m a little scared,” Williamson admits. “I don’t know if my situation will let me move forward sooner — or much later.”

Mallard holds onto hope.

“Things might not go how I want,” he says, “but I can still work toward my goals.”

Sims talks them through every scenario. He taps his head, then his chest. The goal, he says, is to live fully in both places.

“Your peace comes from saying, ‘I’m going to do the next right thing — and however it turns out, it turns out.’”

Hendricks, who bonded out earlier, had said he planned to enroll in welding classes and study cosmetology because he likes cutting hair. But weeks after leaving jail, Sims hasn’t heard from him.

“Hendricks’ story isn’t over,” Sims says.

Kesler, who entered a 12-month rehab program just before the program ended, has talked with his brother about returning to work.

“I joked about being a salesman, but I know he’ll have me on my hands and knees laying floors,” he says, laughing. “That’s what I’m good at anyway.”

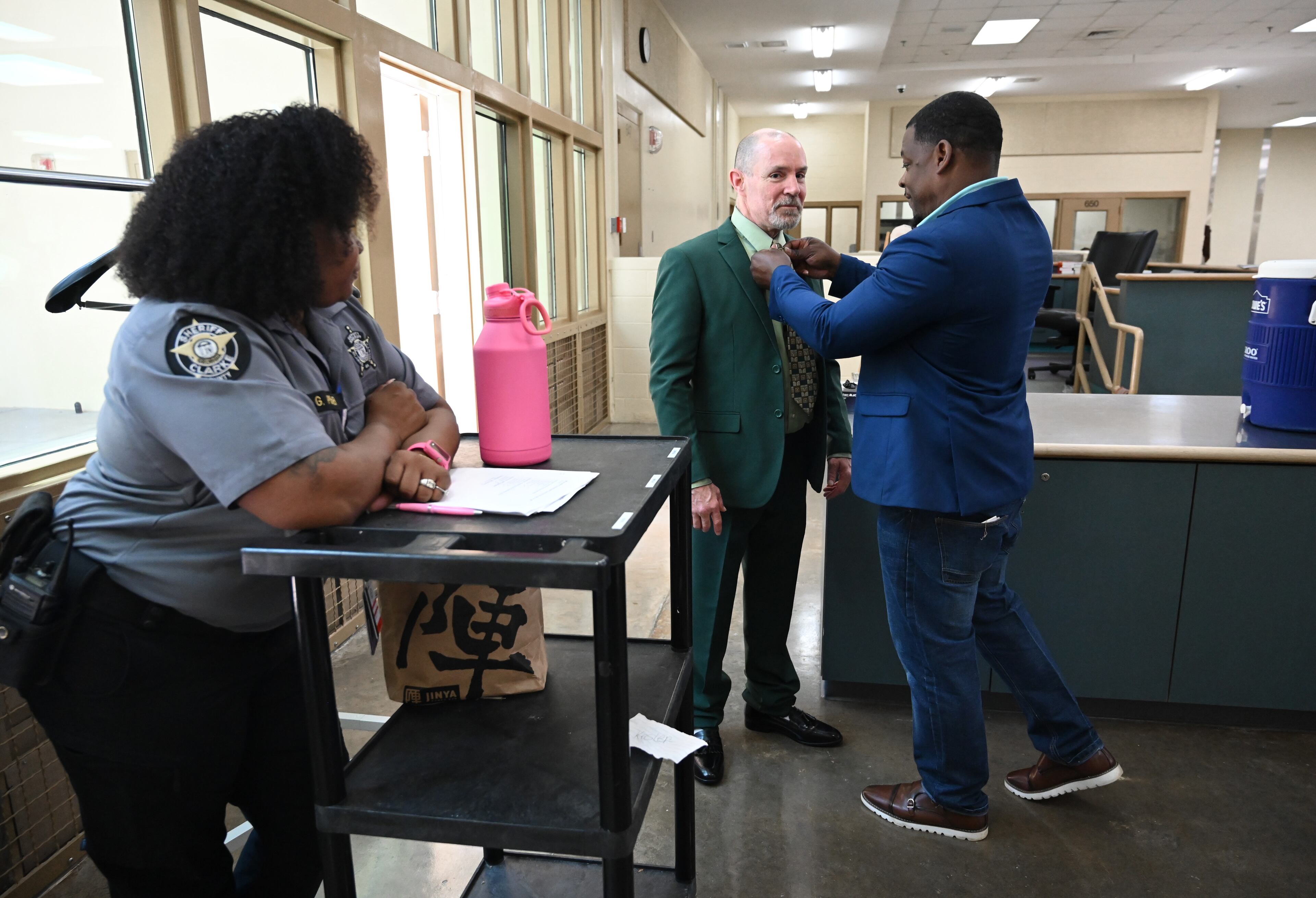

Graduation ceremony

It is June 18.

Of the original 17 men, 11 gather for a graduation ceremony in suits donated by local churches and the Masonic lodge.

For many, it’s their first time tying a tie.

“I think Craft knows how to do a Double Windsor,” Mouzayck says when someone asks for help.

Sheriff Williams, Sims and Woods each stand up to speak. There’s a spread of chicken, baked beans and a big cake.

Hours later, the men line up and walk back to Unit Six. They have two more nights before returning to their former routines, back under constant supervision. A third cohort of the program will begin in late August. Some of the men, including Williamson, have already asked to join.

In the middle of changing clothes, visitors come into the unit, wanting photos in front of the mural. The men scramble to button shirts and grab jackets. Kesler, who has returned for the graduation, is barefoot. Craft’s tie drapes loose around his shoulders. They pose and laugh until everyone straggles out.

One deputy turns to another.

“They don’t want to take those suits off.”