One by one, family members logged onto the Zoom call and cheerfully greeted each other from Atlanta or Detroit. The mood turned somber as they began to speak about the loved one whose life story they only recently had begun to fully understand.

It was 75 years to the day of the lynching of Porter Turner, uncle or great-uncle to most of those on the video call. Turner, found stabbed to death outside of a stately Druid Hills home on Aug. 21, 1945, is considered the last known lynching victim in DeKalb County. A law enforcement officer who infiltrated the Ku Klux Klan later said he overheard members bragging about killing the Atlanta taxi driver.

“He was 49 years old, and his funeral service was held at our family church, Big Bethel A.M.E. Church on Auburn Avenue,” niece Delores Turner told the relatives and community supporters who had gathered. “But this is not how his story ends. Because today, 75 years later, we remember and honor the life of Porter Turner.”

Most of Porter Turner’s living relatives were not born in 1945. And the few who were didn’t know about how he died or kept it a secret.

Calvin Turner, who told The Atlanta Journal-Constitution last year he had vague recollections of family members talking about the KKK killing his uncle, had never told anyone else. His younger siblings and family members had no clue. Calvin Turner died in January; he was 88.

Neither he nor anyone else in the family was aware that Porter Turner had been memorialized at the Equal Justice Initiative’s Lynching Memorial in Montgomery, Alabama, or that the DeKalb NAACP had petitioned the County Commission to include his name on a marker at the county courthouse.

That marker, bearing Turner’s name alongside Reuben Hudson, attacked by a lynch mob in Redan in 1887, and two “unknowns” feared dead after an 1892 confrontation at a Lithonia stone quarry, was installed in May.

Credit: Courtesy

Credit: Courtesy

About a dozen family members drove to Montgomery to visit the lynching memorial and see the DeKalb monument bearing Turner’s name up close. They laid a purple wreath on top of a second monument, a replica on the same property that, according to plans, one day will also be installed outside the DeKalb courthouse.

Druid Hills residents and historians have conducted additional research and are working on a plan to install a second marker close to the site of Turner’s death.

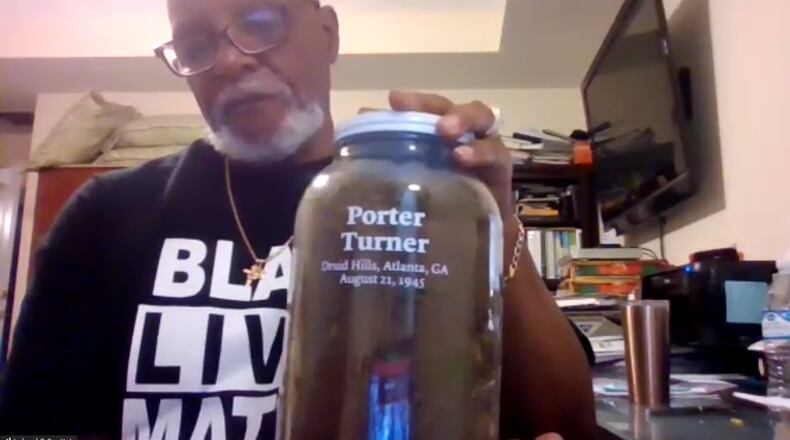

The current owners of the home where he died, who also had no idea that a dark day in DeKalb history ended at their address, gave his family permission to collect soil from their yard. They filled three glass jars with the reddish-brown dirt.

One went to Montgomery, DeKalb officials kept another, and a third remains at the home of Leland Scott Jr., Turner’s grandnephew. He retrieved it and showed it off to the relatives on the Zoom. Then Scott spoke to them about the importance of family and the fragility of life.

“Our lives cannot be bought, paid for, purchased nor extended indefinitely,” he said. “We all have been given one life, and that’s a life to live on purpose. We need to consider what those purposes are.”

About the Author

The Latest

Featured