The first paragraph of Anne Hull’s gorgeous memoir, “Through the Groves,” reads: “A dirt road took us there. When we reached the grove, the Ford hesitated, as if sizing up the chances of a square metal machine penetrating the round world of oranges.” The “us” is 6-year-old Anne and her optimistic father, a fruit buyer, on their quest for the best oranges in Central Florida’s 100-mile stretch called the Ridge, which, in the 1960s setting of the book, had the heaviest concentration of citrus groves anywhere.

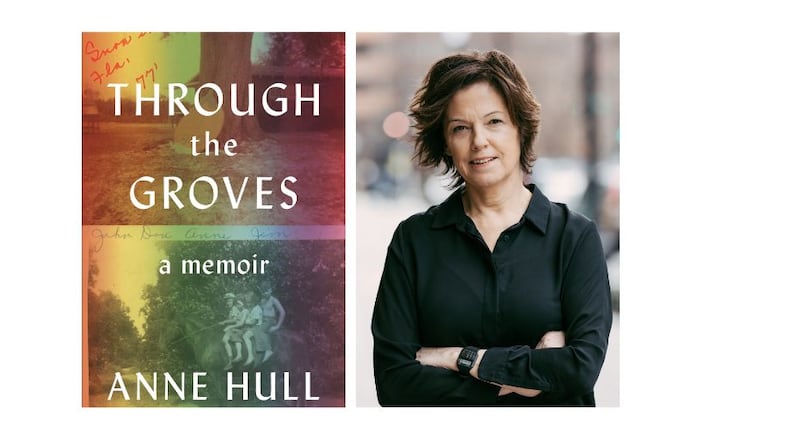

That opening image of incongruity resonates throughout the book as Hull, known for her Pulitzer Prize-winning reporting for the Washington Post, skillfully renders the once “round world of oranges” of her childhood. An evocative coming-of-age and coming-out story, “Through the Groves” is both open-hearted as it stares down the South and the punishing expectations heaped on girls and women, and brave in its inquiry into the unshakable bond of home and self.

Though young Anne sees it as an adventure, accompanying her father to work is her mother’s ploy so that “he’d steer clear of the red neon Schlitz signs that called to him on the drive home.” Her father’s drinking destabilizes their family. To a lesser degree, so does her Brooklyn-born, cultured mother’s disappointment with life in rural Hopewell, Florida, a town established by ancestral Hulls for whom “God and oranges were the cornerstone of life.” Hull’s matter-of-fact depiction of her parents is aptly tinged with the wistfulness of a child becoming aware.

As her parents’ marriage quietly disintegrates, spirited Anne runs shirtless with the neighborhood boys, goes on ice-cream runs with her mother and watches out for her hapless yet loveable younger brother, Dwight, who might be her parents’ favorite. She also becomes acquainted with the growers and workers in the groves who suffer from all kinds of ailments due to pesticide exposure.

Perhaps — it is not entirely clear — Hull’s defiant status as a tomboy is what draws her to other underdogs, including Ceola, the Black babysitter/housekeeper her mother hires when the family moves to Sebring.

“I belonged with Ceola more than anywhere else,” Hull writes of their relationship, one fortified by Juicy Fruit gum and fishing excursions. While the book includes other examples of the this-is-just-how-it-is racism of the 1960s and 1970s South, it is Ceola who personalizes it. When 9-year-old Anne realizes that the truck spraying her neighborhood for mosquitoes does not visit Ceola’s “across the tracks,” Hull still jumps into its “marshmallow fog” with her playmates, though “it was no fun after that.”

After Sebring, there were several more moves to other orange-growing towns, each one increasingly closer to Big Nanny, her paternal great-grandmother who supplements Hull’s father’s income with checks. After her parents split, Hull, along with her brother and mother, move back to Sebring to a “fleabag apartment” where her mother greets guests with, “Welcome to modern poverty.”

Her mother’s resolve to work to support the family is matched by Anne’s growing resentment of her mother’s change in priorities, although the older, wiser author never succumbs to victimization.

Much changes when her mother uproots Anne and her brother (whose name is changed to Jim since Dwight is a Hull name) for a teaching job in St. Petersburg, Florida, where they live with Hull’s maternal grandmother, Damie. Hull’s relatives reinforce societal pressures for females: Aunt Anne offered dolls when Hull preferred a camping kit, and her paternal grandmother Gigi tried to turn Hull against pajamas by starring in her own nightgown fashion show that made her look “like she was going to a prom in bed.” Even her mother “squeezed out of Playtex bondage” when she returned home from work.

But “nutty” Damie indoctrinates her granddaughter into Jackson 5 concert culture rather than gender roles and takes her to Webb City, the “World’s Most Unusual Drugstore,” where she sees a display of mannequin mermaids, “naked from the waist up and long hair covering their breasts.” Hull is not sure why she’s drawn to them, and writes, “This was still a safe period of naivete before the teletype machine inside me started pounding out the reason.”

Hull’s awakening queerness coincides with her father’s resurfacing and her mother’s growing restlessness that culminates with her marriage to Ted, a man she doesn’t love. In earlier chapters, Hull sometimes short-shrifts her own story by focusing on other characters, but not so in later chapters. Now in the early 1980s, Hull seeks to understand her sexual identity and details her relationship with an older woman, “Blue Eyes,” who teaches Hull about the risks of love.

After having lived her entire life up until that point “within a 250-mile radius,” Hull departs to Harvard for a journalism fellowship. Years later, when she returns to Hopewell for a funeral after moving to Washington, D.C., “the dense hedges of shade and fragrance” she once witnessed while traveling with her father are gone. Her memories, however, are not.

Pulsing with humor and tenderness, with characters quirky and vulnerable, “Through the Groves” is a joy. It is a journey back in time, replete with bug zappers, spinning chicken buckets on restaurant signs, sonic booms from the construction of Disney World, CB radio, and roadside fruit stands. It is also Hull’s emotional journey out of innocence that somehow remains quite private, a difficult task to achieve in a memoir. But then again, so is finding out who you really are, how perfectly you fit yourself.

NONFICTION

“Through the Groves”

By Anne Hull

Henry Holt, 224 pages, $26.99

About the Author

The Latest

Featured