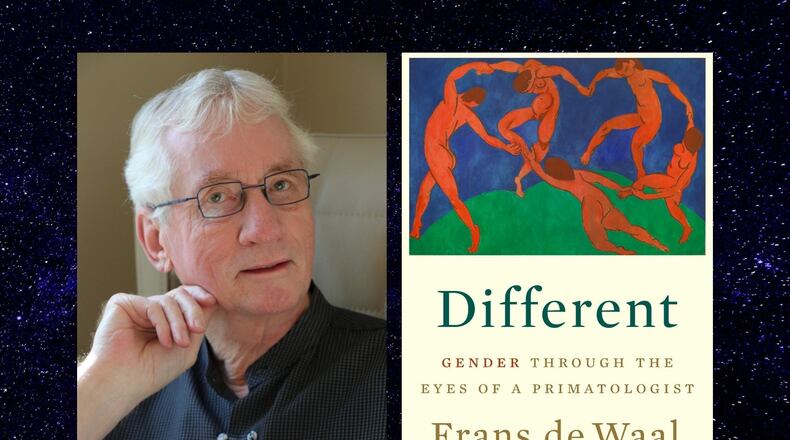

Like everyone else, retired Emory University professor Frans de Waal was housebound for 18 months during the pandemic. Unlike the rest of us, he used that opportunity to write a book, “Different: Gender Through the Eyes of a Primatologist” (W.W. Norton & Company, $30), covering what the scientific study of both humans and primates tells us about sexual identity and diversity, empathy, violence, friendship and more.

Before retiring in 2019, de Waal, who was born in the Netherlands, was director of the Living Links Center at the Yerkes National Primate Center and C.H. Candler Professor of Primate Behavior at Emory. The author of several previous books including “Mama’s Last Hug,” he lives in the Stone Mountain area and likes to hike in Stone Mountain Park with his wife Catherine.

He spoke with The Atlanta Journal-Constitution about “Different;” the conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Q: Let’s start with an important distinction: The difference between biological sex and gender.

A: Sex usually refers to how the male and female differ biologically; the genitals, the hormones, the chromosomes. Sex is largely binary. Gender is much more complex: how the environment and the culture affect us, how they steer us in a certain direction of behavior. It’s better not to describe gender as male and female but as masculine and feminine. It’s on a spectrum and much more flexible.

Q: And people misusing these concepts leads to misunderstandings?

A: It’s unfortunate that in English the word sex is used in two ways: Having sex and being of a certain sex. People found that inconvenient and started using the word gender for biological sex. So, they say “What is the gender of your horse?” The horse has a sex, but it doesn’t have a gender. People are using gender now as a replacement for the word sex, and that has created confusion.

Q: Why did you want to write about this particular cluster of topics?

A: I’ve been in public discussions that have gotten very heated. You have people who deny gender differences, who say we’re all the same and other people who believe that men are from Mars and women are from Venus. You have these polar opposite positions, and people get very invested in them.

As a primatologist, we always talk about the sex of an animal. If someone were to describe to me a primate who kills another primate, I would want to know if it’s male or female because usually females don’t do these things. But when I was giving lectures, as soon as I mentioned sex differences, people were very curious. People were always asking what part is biological and what part is cultural. As if we can decide. We cannot decide.

Q: You make a lot of distinctions among primates, that some primates such as chimpanzees and bonobos are much closer to humans in terms of DNA and behavior than other primates like monkeys and baboons. But aggressive chimps and non-aggressive bonobos are so different. What do these two different species teach us about ourselves?

A: It used to be that we always compared ourselves to chimps. And when (studies of) bonobos came along, which was more recent, some people were upset. Bonobos are more peaceful, they’re more sexual, and the females dominate the males.

In the book I make the triangular connection between both species and humans. There is a perception among some people that males ought to be dominant because that is the natural order of things. What we can learn from bonobos is how powerful sisterhood can be. The chimps can tell us how male relationships can be interesting. They can be rivals and they can even kill each other, but they are also friends at the same time. The two species tell us different things about ourselves. They hold up a different mirror.

Q: Media and social media over-simply and misrepresent studies about primates and what they mean. What is an example of how we don’t understand this science?

A: The most basic one is when we talk about sex in animals we only talk about breeding, that they’re copulating to make babies. To reduce all sex in animals to breeding, which people tend to do, that’s a very narrow view.

We need to have a much broader view, especially in view of what bonobos do. There is sex between same-sex partners. There is sex between opposite-sex partners in periods when no babies are going to be conceived. There is sex done for pleasure. There is sex done for social purposes. That’s why I included a chapter in the book on homosexual behavior in animals, because it’s quite a common thing.

Q: Conventional wisdom is that a lot of animal behavior is instinct, but you push back against that notion. Why is that not a good way to think about animals?

A: The reason I use the term gender for primates is that they are also cultural beings. Apes are very slow developers. The young ones need to learn a great deal before they are competent adults. They pick up techniques of how to eat, how to find food and probably sex-typical behavior, although we need more research on that.

Q: You write in your chapter about rape that males grow up stronger than females and more prone to violence, so human society needs to “find ways to civilize its young men.” Do you have any ideas how to accomplish that?

A: I’m not an educator or a psychologist. But sometimes people say we should have a gender-neutral upbringing of children, bring up children as if they don’t have a gender, and I have trouble with that. You cannot raise boys and girls the same way, you need to tell them how they should behave with the other gender. Especially for the males. Because I think males need to be taught that they have a responsibility, being stronger than the females, to control that strength, to use it for good purposes instead of bad purposes. And college students need to learn the same thing, not just young kids.

Q: Transgender individuals are the source of battles in the culture wars right now. If I understand your book, transgender doesn’t exist in the animal kingdom, but there is frequently a fluidity of behavior that supports the notion of transgender persons. Is that right?

A: I cannot confirm that it exists in animals because I cannot ask my subjects how they identify. I do describe in the book one female chimp named Donna who acted like a male, but we knew she was a female. Is that transgender?

Clearly it is possible for individuals to be born as one sex and then start acting like the other sex. We see male chimps who don’t play the status game, don’t play the competition game. They may be big strong males, but they don’t have it in them to compete with other males. I find that interesting.

If you walk in Stone Mountain Park, you can see that every tree of the same species is different. In biology, we are very used to variability. Every individual has its own makeup. And the same thing happens in humans.

Q: At one point in the book you quote the sex researcher Alfred Kinsey: “The living world is a continuum in each and every one of its aspects.” But people insist on rigid categories.

A: Yes, we tend to carve up everything and have labels. We label everything: Homosexual, heterosexual, bisexual. Also, racially we have all these labels: Black, white. Even though underneath there’s an enormous genetic continuum going on. In biology we’re very used to that. In society we like to put people in pigeonholes.

About the Author

The Latest

Featured