“Deer Creek Drive” by Mississippi novelist Beverly Lowry is a nonfiction retelling of a Washington County socialite’s 1949 conviction for brutally murdering her mother. In the resurrection of Ruth Dickins’ story, Lowry blends a memoir of her own formative years with an accounting of the Delta’s 1950s racial climate by drawing from historical fact as much as her own recollection to recreate a snapshot in time of the “unreconstructed South.”

One November afternoon on Deer Creek Drive, the most desirable residential avenue in Leland, Mississippi, society matron Idella Thompson was found dead in her bathroom, stabbed upwards of 150 times. The pruning shears her daughter Ruth Dickins had brought over earlier that day to trim the rosebushes were wiped clean and lying nearby. At the scene, police found Dickins, composed, injured from defensive wounds and covered in blood. She fingered a “young, slightly built, dark-skinned Negro” as her mother’s murderer, whom Dickens said she happened upon during the act and was forced to fend off.

As a longtime member of the “planter aristocracy” who was accustomed to access and privilege, Dickins, sans her attorney, comported herself with arrogance, bossiness and “an unladylike tendency to tell it like it is” while being questioned as a witness.

Once it became clear the accused didn’t exist, Dickins became the primary suspect and was arrested for her mother’s murder. What ensued was a sensationalized trial capturing the media’s fascination that was conducted as much in a court of law as in the frenzy of public opinion.

Author Lowry was the adolescent daughter of a moderately successful conman living in nearby Greenville, Mississippi, who recalls that she and her friends and female relatives “consumed every written word (about the trial), studied every picture, speculated endlessly, imagining, envisioning, casting back to remember where we were when we heard the news, who told us, exaggerating what we knew and how it affected us, to create the story we passionately wanted, needed, to believe … She did it. Of course she did.” Lowry weaves her own family history into the record of Dickins’ highly publicized ordeal. But it doesn’t take long to realize their stories do not intersect.

“Deer Creek Drive” is not the first time Lowry has combined true crime with her memoirs. In the 1980s, while in the throes of despair over the hit-and-run death of her son, she became fascinated with Karla Faye Tucker, a Texas death-row inmate who had murdered two men with a pickax. Lowry visited Tucker in prison for many years prior to her 1998 execution, and the two women formed an unlikely friendship that Lowry chronicled in her 1992 book “Crossed Over: A Murder, A Memoir.”

While the juxtaposition of Lowry’s grief and Tucker’s redemption forms the foundation of “Crossed Over,” the inclusion of Lowry’s childhood recollections in “Deer Creek Drive” don’t provide the same link. In a book chock-full of characters — from the many members of Dickins’ prominent family to the multitude of law enforcement and legal personnel to myriad reporters, politicians and members of the community — the inclusion of Lowry’s history seems superfluous to Dickins’ story.

Lowry addresses many contrasts between her and Dickins’ reality — such as how her family was transient and moved nearly every year while Dickins’ multigenerational wealth firmly planted her on Deer Creek Drive, and how Dickins’ family evaded the polio epidemic by indulging in summer-long, out-of-state vacations while Lowry’s mother became disabled from the disease. A more targeted examination of classism could have fused their storylines together.

Instead, Lowry focuses on the racial friction prevalent between World War II and Martin Luther King Jr.’s 1955 sermon in Montgomery, Alabama, following the arrest of Rosa Parks — what Lowry calls “the real beginning of the civil rights movement in this country.” Short of Dickins’ accusation that a nonexistent Black man committed the crime, which never gains momentum, this story isn’t about racism. Racial tensions obviously factor into any narrative set in 1950s Mississippi, but the intersection of sexism and classism play a more prominent role and are left relatively unexplored.

Lowry makes a strong, albeit brief, argument about gender discrimination when she points out that Emmett Till’s male murderers were swiftly acquitted while Dickins spent years in prison for a conviction based on circumstantial evidence. Further exploring the sexism inherent in racism could have made a profound impact in this narrative, yet Lowry barely scratches the surface before moving on.

Ultimately, Lowry’s “reckoning” is more of an account of how racially imbalanced things used to be than an attempt to heal past wrongs and, unfortunately, doesn’t bring a new perspective to the conversation. She admits that at the time, she would have laughed had someone informed her that participating in a cotillion contributed to white supremacy, but she doesn’t venture any deeper than her own ruminations to explore a greater social context.

Lowry packs a lot into her ambitious and convoluted true-crime memoir but ultimately brings it back to Dickins. The conviction of a wealthy white woman served to divide her community for decades. By the end of “Deer Creek Drive,” Ruth Dickins has suffered dearly for either her arrogance or her guilt. With no conclusive way to discern the truth, it’s left up to the reader to decide.

NONFICTION

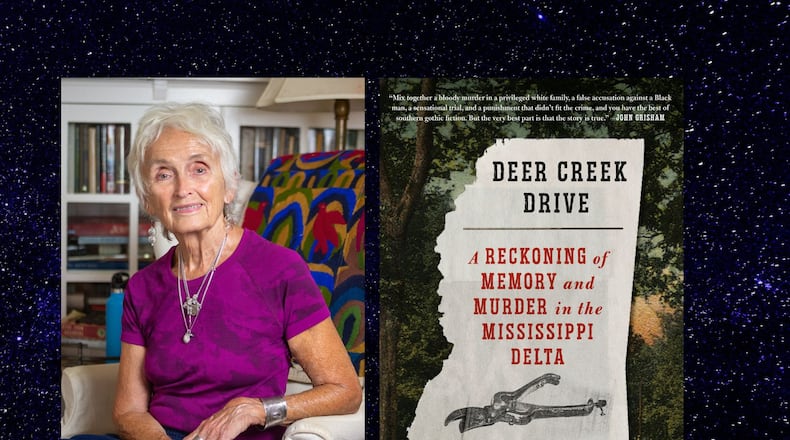

“Deer Creek Drive: A Reckoning of Memory and Murder in the Mississippi Delta”

by Beverly Lowry

Alfred A. Knopf

368 pages, $29

About the Author

The Latest

Featured