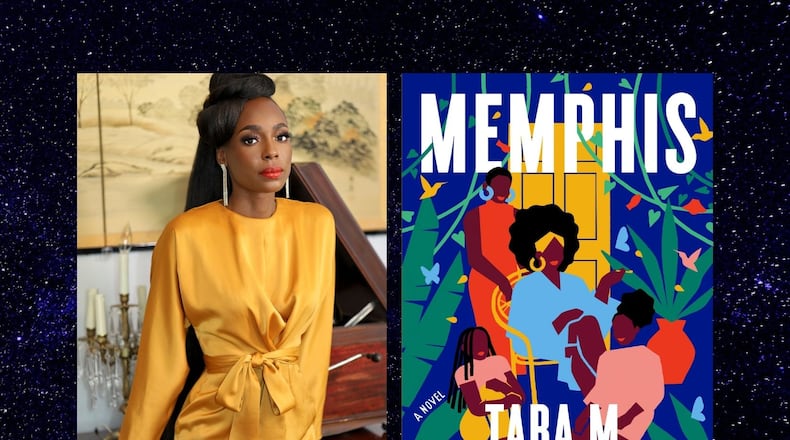

Tara M. Stringfellow’s “Memphis” is a lyrical novel told in vignettes centered around the sorrows and joys of four Black women from a Tennessee family. The beautiful and bold North women persevere through an inheritance of brutality and injustice, and the lasting impact of generational trauma, on the road to actualizing their independence.

Miriam North has craved “simple, Black love” all her life. She thought she found it in the dashing Marine who swept her off her feet and — much to her mother Hazel’s chagrin — moved her away from home. After an incident of violence ends nearly two decades of marriage, Miriam packs up her little girls and returns to her ancestral home in Douglass, a community North Memphis, to start over.

The younger of the North sisters, August, gladly welcomes Miriam home. But there’s unresolved history looming behind the yellow door of their stately familial residence. A horrible abuse was perpetrated against Miriam’s 10-year-old, Joan, in that house. It wasn’t the first time an extreme act of malevolence rocked the North family’s foundation, though.

As the novel unfolds, Hazel, Miriam, August and Joan each take turns recounting more than 60 years of their interconnected lives. Like the quilts the North women piece together to commemorate their milestones, each chapter homes in on a specific moment in time. Spanning from the 1930s to 2003 in nonlinear, succinct segments, the patchwork of “Memphis” starts to take shape. Sometimes sharing their own experiences, sometimes reflecting on each other’s, the women tell stories that coalesce into a dazzling display of female resilience.

Stringfellow drew from her own family’s folklore to craft her saga. In the 1950s, Hazel’s husband, Myron — a character fashioned after Stringfellow’s grandfather — becomes the first Black homicide detective in Memphis. He’s lynched by his all-white police squad days before Miriam’s birth. Hazel, whose arc follows the experiences of Stringfellow’s widowed grandmother, enrolls in college and becomes one of the first Black nurses in Memphis.

Each woman’s power to choose her own future is challenged as time moves forward. August is a single mother with a problem child in the ‘80s. Fearful of losing custody, she abandons her dream of becoming a doctor to open a beauty salon in the back of the house so she can supervise her son.

In the ‘90s, Miriam is exhausted from nursing school and work. She struggles to guide Joan’s future while battling her own regrets. Joan is a gifted artist with a talent as big as her dreams. But Miriam wants Joan to follow their matrilineal tradition and enter the medical field. Challenging Joan to prioritize practicality, Miriam says, “Name me one successful artist with a dark face. With breasts. Name one Black woman famous artist. Go on. I’ll wait.”

There’s a sprinkle of romanticism dusted across the pages of “Memphis” that reveals itself in extremes. In Stringfellow’s narrative, there are good men and there are bad men. The good men, like Myron, tend to die young, while the male characters who inflict harm seem blessed with longevity. Instead of leaving her characters to stew in victimhood and bellicosity, Stringfellow humanizes their roughness by digging into the myriad ways bigotry and trauma have shaped their realities.

There’s a non-graphic incidence of child brutality against Joan in the beginning of the book that, although horrifying, Stringfellow uses to lay the groundwork for the long-term growth and redemption of both Joan and the perpetrator. It’s this generosity of spirit, sometimes guided by faith but not always, that appears throughout the narrative and propels each character forward.

Stringfellow paints a vivid picture of how generations of racial oppression have shifted the source of violence over the years. In Myron’s day, the threat comes from outsiders when he is murdered by the police squad. In Miriam’s and August’s adulthood, their magnificent home, once situated in a proud Black neighborhood, “is the hood now,” says August. “There’s a gang war in this place. They shoot children walking to school now.” By the time Myron’s grandchildren are coming up, the source of aggression has manifested within their own bloodline.

Despite this decline, the sense of community in “Memphis” is a constant source of strength. The night Myron is murdered, “all of Douglass … stood on the steps of the porch of the house Myron had built for Hazel, stood on the lawn, climbed up in the branches of the magnolia and found seats where they could. The people in the neighborhood stood watch that night. Stood there all night. Not a one saying a word. Stood watch over Hazel and her baby. Some of the men fetched their old war uniforms. Stood saluting the house. That whole night.”

It’s not just protection the community offers; it also fosters joy. A resounding sense of solidarity emerges as the women in Douglass prop up each other through life’s tribulations. At the center sits August’s beauty shop, the cornerstone where they all come together. As Joan’s childhood recollection reveals, “The framed record covers on the walls shook with the laughter. Laughter that was, in and of itself, Black. Laughter that could break glass. Laughter that could uplift a family. A cacophony of Black female joy in a language private to them.”

Pulsing with heart and beating with soul, “Memphis” is at once a multigenerational celebration of Black culture and womanhood, a chronicle of perseverance and strength, and a love letter Stringfellow wrote to her family when she gave their stories her voice.

FICTION

“Memphis”

by Tara M. Stringfellow

The Dial Press

272 pages, $27

The Latest

Featured