‘If I Survive You’ employs dark humor to explore identity

Jonathan Escoffery plunges directly into the angst caused by growing up racially ambiguous in America in the opening story of “If I Survive You,” his unflinching collection of linked stories about a Jamaican family that migrates to Miami. As the narrative ventures deeper into the diaspora experience, Escoffery paints a vivid picture of the first-generation perspective by scrutinizing the cultural differences between children who are born stateside and their parents who are not, and the complex ways this impacts their relationships. The result is a revealing, often humorous and somewhat twisted collection of stories that are as engrossing as they are memorable.

One of the most delightful aspects of “If I Survive You” is Escoffery’s multifarious use of literary devices. From second person to dialect to present tense, his debut collection is rife with shifting mechanisms that provide intimate access to his characters and submerge the reader in the urgency of his world.

“In Flux” opens with the protagonist, Trelawny, who, in a punching deployment of second-person you, chronicles the series of racial classifications he is assigned over the course of his childhood. “You’re a rather pale shade of brown, if skin color has anything to do with race,” Trelawny narrates as he explores the ever-present question that haunts his formative years: What are you? Initially he proclaims American, but that fails to satisfy and instead exposes him to microaggressions and blatant aggressions as the individuals he encounters seek to categorize him as something they understand.

Trelawny’s observation about his hair encapsulates the nebulous sense of frustration he endures trying to find where he belongs. “Some of it shoots straight out in singular strands, while other parts cling in wavy, feathery tufts and still others spiral in tight coils. Not even your hair agrees on what it should be,” he laments. The piece provides powerful immersion into the isolating experience of not fitting into any world.

In the second story, “Under the Ackee Tree,” Escoffery switches gears by penning the entire chapter as a hypothetical. “If you are the only son of uptown Kingston parents,” the narrative begins as the use of patois quickly reveals the perspective has shifted to a different character. But it isn’t until it becomes obvious how the stories relate that Escoffery’s brilliance reveals itself. Topper is Trelawny’s father and his storyline answers a multitude of questions Trelawny’s opening story raised. Escoffery uses the next six stories in his collection to construct a painful and nuanced portrait of the tenuous relationship between a Jamaican father and his American son.

Fatherhood is a theme Escoffery explores from a multitude of angles and viewpoints. Paternal expectations manifest differently in Topper’s relationships with his two sons. His eldest, Delano, is his Jamaican-born favorite who looks and talks like Topper. Trelawny possesses none of their qualities and his unfamiliar characteristics drive a wedge between father and son early on. As he spends years grappling for Topper’s acceptance, Trelawny and his father take turns wounding each other in targeted ways.

In “Splashdown” a different paternal relationship is explored by Trelawny’s cousin Cukie when he connects with his deadbeat dad for the first time at 13. Seeking to decipher what kind of man his father is, Cukie “lifted one of Ox’s folded shirts to his nose, inhaling. If he could detect goodness, or remorsefulness, or deceit, what would they smell like?” Unfortunately, the shirt offers no warning. Initially Cukie and Ox fulfill a need in each other, but ultimately the relationship is doomed. It speaks loudly to the influence even absent fathers hold over their sons and introduces an undercurrent of macabre to these stories.

A restrained morbidity starts to emerge as Escoffery uses the sadness of the absurd to magnify undesirable aspects of humanity. In “Odd Jobs” Trelawny is broke and living in his car. He answers a woman’s job posting on Craigslist seeking a person to punch her in her face. Their exchange is equally riveting and revealing but ultimately does not go well for Trelawny.

The title story, “If I Survive You,” takes an even stranger turn when Trelawny answers an ad to “watch my boyfriend and I,” sandwiching him between a wealthy white couple who toy with Trelawny’s desperation and the reaction their friends have to his race. These stories are as uncomfortable as they are fascinating, doom and trepidation driving both the characters and reader forward as the ugly side of human behavior spills across the page.

Another theme Escoffery weaves into these tales is how Florida’s climate impacts the people who inhabit the land. Be it the flora and fauna Trelawny battles in “Pestilence” or the displacement Hurricane Andrew inflicts on Topper and his family, Mother Nature plays an integral role in each of these stories.

Even the hurricanes that don’t make landfall leave their mark. In “If He Suspected He’d Get Someone Killed This Morning, Delano Would Never Leave His Couch” — a story that is particularly amusing until it turns morbid — Delano races around town trying to secure his payday before Hurricane Irene strikes. Disaster ensues before Irene turns directions, leaving his life worse for his harried, and in hindsight unnecessary, efforts.

“If I Survive You” starts out intense and immersive but then settles into a character-driven collection of eight connected stories that shine a light on the fable and folly of contemporary life in the United States. Exhuming powerful issues of identity and belonging, Escoffery raises his bright and compelling voice to ask: What does it mean to be an American? And who gets to decide?

FICTION

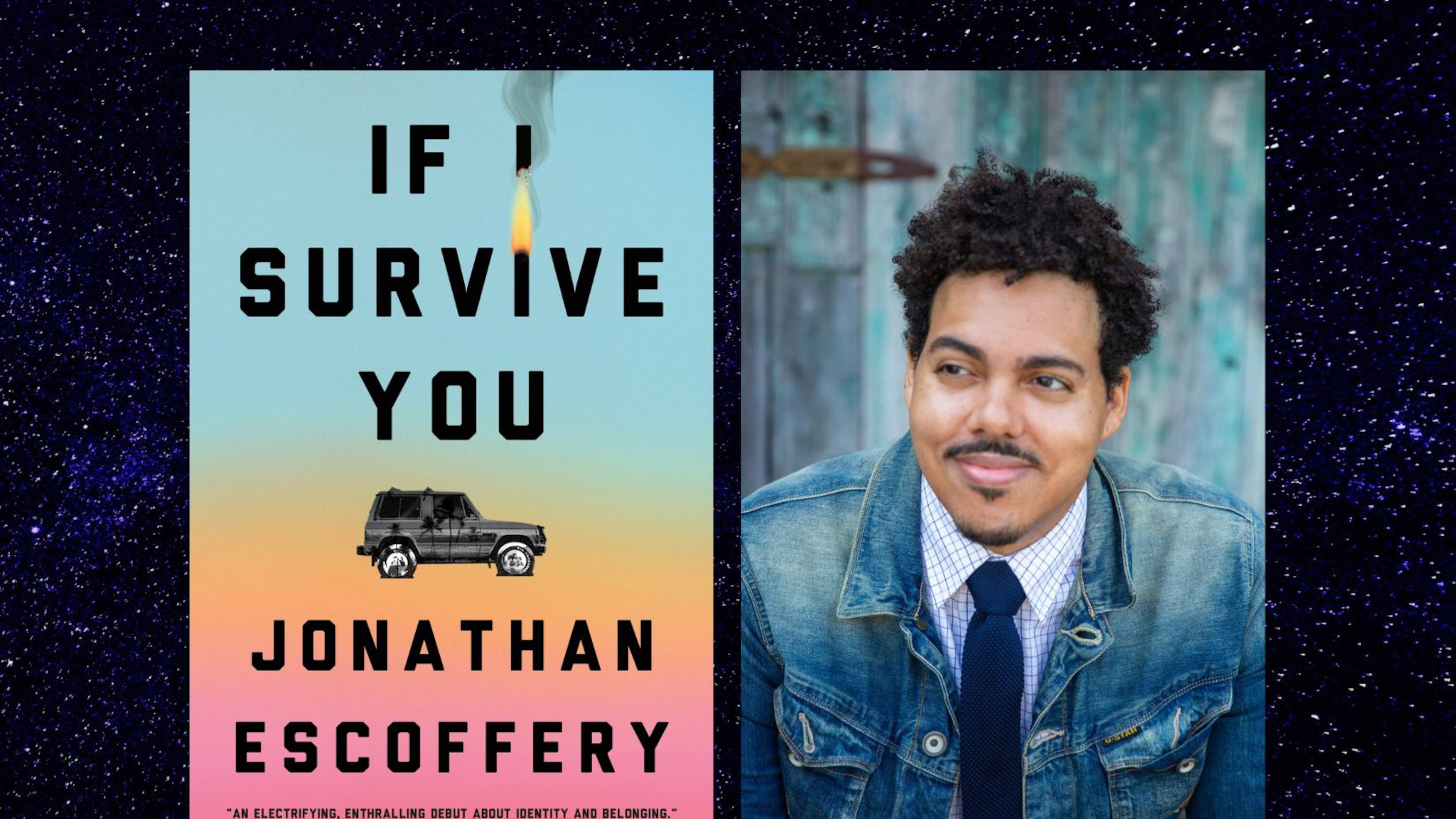

“If I Survive You”

by Jonathan Escoffery

MCD

272 pages, $27