Valerie Boyd, author of “Wrapped in Rainbows: The Life of Zora Neale Hurston” and editor of “Gathering Blossoms Under Fire: The Journals of Alice Walker, 1965-2000,” wrote the following introduction to “Bigger Than Bravery” (Lookout Books, $18.95), an anthology of essays and poems by some of the country’s leading Black writers that she edited before her death earlier this year.

My daddy was not a numbers runner — though he was once mistaken for one and arrested.

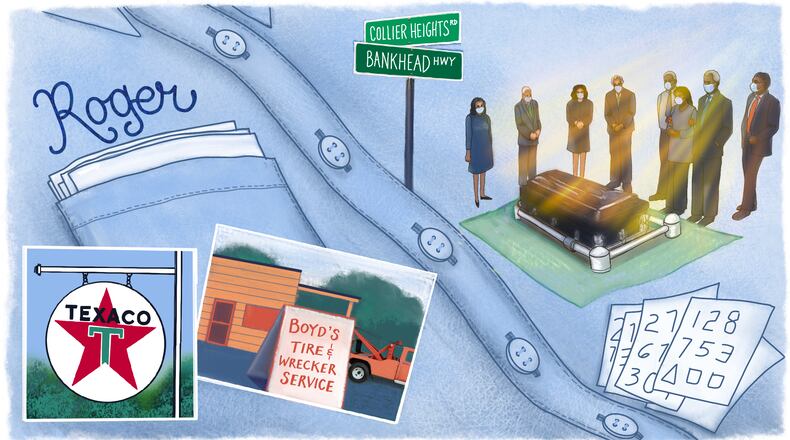

Back in the 1960s and ‘70s, playing the numbers was a common pastime in Black neighborhoods in urban communities like Harlem, Chicago and Atlanta, where I grew up on the west side, somewhere between Bankhead and Collier Heights.

Working men, homemakers, single mothers and corner dwellers would whisper a three-digit prayer to the neighborhood numbers runner, who’d jot down the wish-fulfilling formula on a betting slip. Years later, state lotteries would offer a similar game, effectively shuttering the businesses of Black numbers runners and bankers. But back in the day, it was a racket controlled by Black men and women in their own communities. Though illegal and sometimes dangerous, it offered the promise of a shaky stepping-stone to better financial days for runners and players alike.

When I was around 8 years old, police raided my dad’s Texaco franchise and found a coffee-stained desk littered with small slips of paper, each inscribed with mysterious hieroglyphs in my father’s lean, jaunty handwriting. The thin sheets, carefully separated from the perforated seams of a miniature writing tablet — not the raggedy chaos of a spiral-bound notebook — were profit and loss statements for the day, the week, the month. The stacked papers fit neatly into the breast pocket of his light-blue work shirt, stitched with his name, Roger, in loose, cursive letters. My mom jokingly referred to that pocket as his “office,” and it was filled, seam to seam, with the scrawls of three-digit codes, just as baffling as the ones police found on the underutilized desk — and apparently just as incriminating.

When he rang my mom from a pay phone at the Fulton County Jail, we three kids were incredulous, and our mom was indignant. Roger Boyd was an upstanding citizen, a respected businessman, a deacon in the Baptist church, a young pillar of the community who comported himself with the understated Alabama dignity of Hank Aaron. On Sundays, when he wasn’t in his blue work uniform, he wore dark gray, blue and black suits like John Lewis, Andrew Young and the other civil rights titans he admired, though they were his peers, age-wise, and occasionally dropped by his Texaco for gas and a complimentary window wash. Full service.

Credit: TNS

Credit: TNS

When my dad finally came home, late into the night, he regaled us with stories of his day in jail, and he laughed at the case of mistaken identity. I don’t recall him being enraged or insulted or frightened. Maybe he felt all of those things, but if he did, he didn’t say.

* * *

During the height of the oil crisis in the mid-1970s, when the nation faced crippling petroleum shortages and steeply elevated gas prices, my dad couldn’t afford the gas to keep his Texaco stocked. One day, he rushed home and announced in a tumble of words: “All the money in the house; I need it right now!” At 10 years old, I had managed to save about 50 hard-earned dollars. A part of me thought my money was a secret and maybe I could get away with not offering it up to the family cause. But I knew we were bound to starve or thrive together. I turned over my piggy bank, and the gas station survived another week.

Soon after, though, my dad gave up the Texaco — one of the few such Black-owned franchises in the South — and spent a week at home in his undershirt and socks looking at newspaper want ads.

For as long as I could remember, he had been up and at ‘em by 7, having his second cup of coffee with my mom, then onto his day as the Great Provider. I had never seen my dad work for The Man — hell, he was The Man — and I’d certainly never seen him sit on the couch during the workday with no shoes on.

As I watched him flip through the classifieds of the Atlanta Constitution, I briefly wondered if our family life as I knew it was over. In his 30s then, he had a wife who was a stay-at-home mom and three children to support. I imagine he must have felt immense pressure, but — to us, at least — he didn’t say.

The next thing I knew, he’d rented a small building on Bankhead Highway, a couple of miles away from his old gas station. Someone hand-painted the sign for him: boyd’s tire & wrecker service. He still had the tow truck from the gas station. As long as people were driving cars, they’d need tires, he reasoned, and this would be his great comeback. It was a moment of glory for us all; my mom, my two brothers and I believed in him and banded together in our family business.

On Sundays after church, we opened the shop for afternoon sales. The building, which my mom persistently called “The Milk Jug” in honor of its past life as a drive-through convenience store, was so small that the tires and the humans couldn’t all fit at once. She and I worked the cash register inside while my dad worked the customers outside — my brothers watching him and memorizing. It was like an alternative happy ending to “A Raisin in the Sun.” Dad eventually moved the business to a larger building down the street, where he remained for 35 years before reluctantly retiring.

* * *

When Dad passed away on Wednesday, July 8, 2020, we weren’t ready.

We had just bought him a new mattress and box springs for Father’s Day, so he could get a more comfortable night’s rest — not knowing we’d be ushering him to his final resting place so soon. My college-age niece, grounded at home by the pandemic, was assembling the box springs inside the small brick house that my dad shared with my older brother, Mike. Father and son stepped outside to give her more space. When my dad leaned against his walker, it rolled away, and he fell.

A broken hip is a tough diagnosis at age 82. COVID-19 prevented us from visiting him in the hospital, but his surgery went well. It looked like he’d spend a few weeks in rehab, then come home. We were relieved, until Mike began to receive disoriented calls from Dad in the middle of the night. “Why haven’t y’all come to visit me?” he demanded, seeming to forget everything he knew about the pandemic. “Come get me out of here!”

My brother would remind him that hospital rules didn’t allow us to visit, but that we’d been speaking to him and his caregivers every day.

Credit: THRASHERphoto

Credit: THRASHERphoto

During the waking hours, he seemed lucid again when we talked with him. On what turned out to be his final full day on earth, he called each of his three children individually. His voice was as relaxed as it had been nearly 50 years earlier, when he’d told us of his escapades in jail that day he was mistaken for a numbers runner. When I asked what he needed, he said, “Nothing. I’m just calling to check on you, to make sure you’re all right.” The Great Provider. The Protector. The Dependable Dad. If he was worried about getting well, or how much time he had left, he didn’t say.

The next day, a nurse called. He had developed pneumonia and was having trouble breathing. They were moving him to the ICU, and we should get there as soon as possible. Before we could find our keys, he was gone.

We weren’t ready. We still aren’t. When Dad died, he “left us to act out our ceremonies over unimportant things,” as the great Zora Neale Hurston wrote of her own mother’s death. And so we acted out our ceremonies — muted though they were. Instead of the 300-person homegoing celebration that a man of my father’s stature should have had, the pandemic forced us to speed through a 10-minute, masked graveside funeral with fewer than 10 attendees. Just his three kids, his one grandchild, and a few close cousins and friends.

People I don’t even know still call my brother, outraged that we buried Roger Boyd — businessman and pillar of the community — and didn’t let them know, that we didn’t give them a chance to say their own good-byes to a truly good man.

We regret their disappointment, but we have had to reckon with a harsh reality of the pandemic: Maybe every Black funeral can’t be an hours-long affair, punctuated by a respectful recitation of the deceased’s favorite scripture, a sober intoning of his favorite hymn and a gut-wrenching rendition of “Precious Lord, Take My Hand.”

Maybe a swift, stand-up funeral now has its place in the pantheon of Black grief rituals. After all, as Toni Morrison wrote in her slender 1973 masterpiece, “Sula,” we must meet some feelings on our feet. “Then they left their pews. For with some emotions one has to stand.”

We finished the ceremony, gave and received masked hugs and were back in our cars in less than 12 minutes. The quick, efficient funeral reminded me of my dad’s profit and loss statements, packed neatly in his shirt-pocket office.

As we mourned the colossal loss of Roger Boyd, it was the hardest of hard days. But when the sun came out and drenched our little family of strivers in kaleidoscopic light, I considered that magical sunlight a gain. I knew my father — somehow, somewhere — was to thank for it.

* * *

In “Bigger Than Bravery,” 31 Black writers take stock of what we’ve gained and what we’ve lost, of what the pandemic has taken from us and what it’s taught us. Together — in poetry and prose that is both public and private, intimate and expansive — these literary artists model and embody resistance, resilience and hope.

Consider this anthology an offering, a modest sacrament to help us fill the empty places within. A thoughtful convergence of poetry and essays, the book is organized so that the pieces are in intimate conversation with one another, with the poems serving as deep breaths between the longer narrative essays. If you allow, this book can be a long exhalation, a silent prayer, a solace and a comfort as we reach toward the promise of brighter days ahead.

This excerpt from “Profit and Loss” © Valerie Boyd, introductory essay from “Bigger Than Bravery: Black Resilience and Reclamation in a Time of Pandemic,” was published with permission from Lookout Books.

About the Author

The Latest

Featured