When Ailey Pearl Garfield decides to become a historian instead of continuing her patrilineal line’s five-generation tradition of becoming physicians, she replaces the mantle of family legacy with the responsibility of telling the truth about America’s history, her family’s origins and her own unspoken burdens in “The Love Songs of W.E.B. Du Bois” by Honorée Fanonne Jeffers.

“Women push the family forward, Ailey, not backward. You are very, very brown, so you must find someone much fairer than yourself. You must think of your children,” Ailey’s paternal mother Nana, who regularly passes for white and is obsessed with colorism and class, tells her. Ailey sets out to help her family advance by doing things her way, shirking off many of the social, cultural and economic anxieties foisted upon her by others. What she will uncover during her coming of age and later as a historian changes the way she and those around her define family, and the way readers think of American history.

The majority of the novel takes place in two locales: “the City,” a thinly disguised Washington, D.C., where Ailey’s parents work and she and her older sisters Lydia and Coco are raised, and a small settlement in Georgia near the Ocoee River once called The-Place-in-the-Middle-of-the-Tall-Trees but now known as the town of Chicasetta. Ailey’s matrilineal line is from this place, and her ancestors have been rooted in the land since before the founding of the country.

Weaving an epic from the choices, traumas and betrayals of women into a detailed, multi-generational family story that spans hundreds of years is an ambitious undertaking, and it could fall apart in the hands of a lesser-skilled storyteller. The interspersed “songs” that the novel’s title refers to ties Ailey back to her ancestors like Kiné, the Wolof-speaking woman forced to cross the Atlantic as part of Middle Passage who ends up on Wood Place plantation near Chickasetta.

The way Ailey’s ancestors speak to her — and perhaps through her — in these interludes and in articles found in the archives create a sonorous work that rings true to some of the essential truths about this country and its treatment of Afro-Indigenous people: “Jeremiah didn’t own one acre to his name, and land was what white men throughout history of this nation had killed and employed deceit to get. Land occupied a space in white pride, and a white man without land was no better than the Black man he had enslaved or the Indian he had stolen from, through murder and connivance and a lack of sympathy.”

With lines like this Jeffers, through Ailey’s analysis of her family history, sums up the battle for the soul of America. Arguably, all of America’s issues and discriminatory policies hearken back to the desire to possess land and exploit what can be done on it. From broken treaties to the selling of Black people who were born in America as freedmen, the novel contains an arresting story that could only happen in this country. As the conductor of this masterwork, Jeffers works nimbly to address generational trauma, rape and sexual abuse without falling into the well-trod trap of extraneous graphic violence and Black suffering. There is brutality here, but there is also affection, devotion and, to hear the characters tell it, love.

Over the course of the novel, readers become intimately acquainted with Ailey’s desire for autonomy — the women in her line often had their choices shaped by men, and Ailey is determined to find her personal agency. “His movements didn’t feel good to me, but I felt powerful, that I could make him tremble and pant. I was in control and that was important because I was tired of people either telling me what to do or lying to me. I wasn’t going to take it anymore.”

Several of the novel’s major plot points and reveals turn on the fact that the success of men in the region came at the expense of Black women and the negation of the grief, abuse and sacrifices they endured before being mythologized for their suffering. The work that Ailey does in the archives seeks to give women who only exist on the periphery full, luminescent lives.

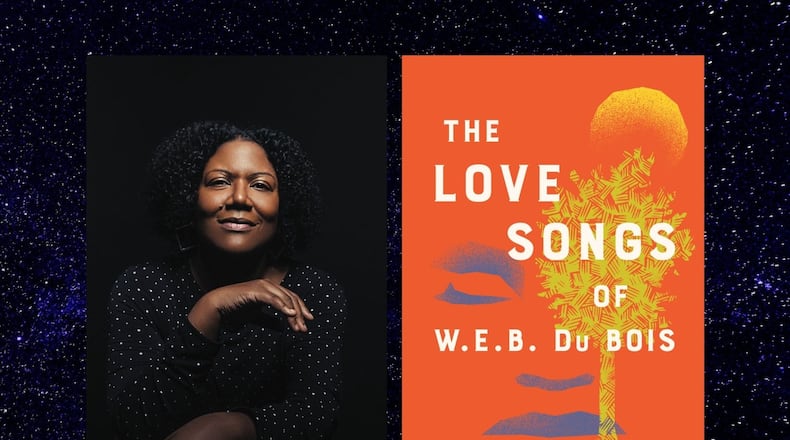

Jeffers, whose poetry collection “The Age of Phillis” was longlisted for the National Book Award in 2020, is adept at stripping away the romanticized storylines about who shaped the foundation of American society and in exchange fleshes out the lives of Black women intentionally left out of lore and historical archives.

Even though there is a large cast of characters and multiple plots functioning at once, Jeffers’ ruminations do not lose their focus. The narrative thread is always held tight in the hands of a capable storyteller. The characters — even the despicable ones like Samuel Pinchard, a white Scotsman with “strange” eyes who befriends Ailey’s Afro-Indigenous ancestors before betraying them — are meticulously wrought and fully developed. Jeffers’s crafting of Ailey’s fictional excavations is compelling, and the novel never loses its urgency.

With “The Love Songs of W.E.B. Du Bois,” Jeffers has created an opus, an indelible entry to the canon of contemporary American literature and one of the foundational fictional texts of Black literature worthy of sitting alongside Ralph Ellison’s “Invisible Man,” Toni Morrison’s “The Bluest Eye” and Jesmyn Ward’s “Sing, Unburied, Sing.”

FICTION

“The Love Songs of W.E.B. Du Bois”

by Honorée Fanonne Jeffers

Harper

816 pages, $28.99

About the Author

The Latest

Featured