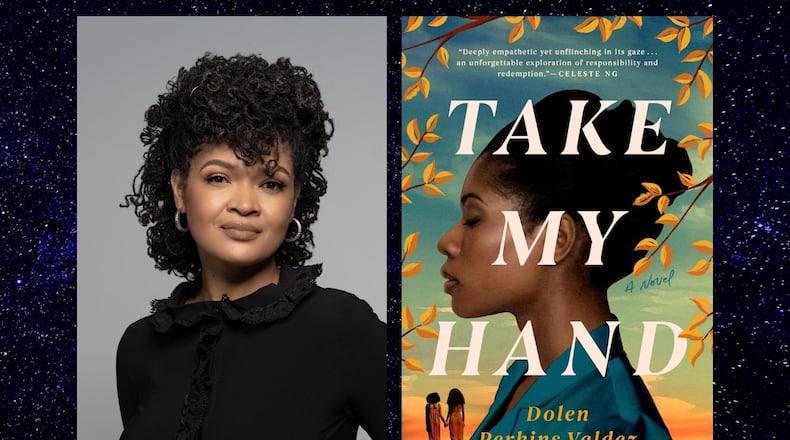

“Take My Hand” by Dolen Perkins-Valdez is a fictionalized retelling of a 1970s Supreme Court case concerning the sterilization of two sisters, ages 12 and 14, in Montgomery, Alabama. While examining the history of medical racism in the United States and its life-changing impact on two young girls, Perkins-Valdez provides insight into how, when administered bereft of dignity, the assistance offered to disadvantaged recipients can prove as detrimental as living in poverty itself.

The educated daughter of a doctor and an artist, Civil Townsend is full of good intentions when she takes a job as a nurse at the Montgomery Family Planning Clinic in 1973. The clinic was established to provide no-cost birth control to reduce the state’s number of unmarried mothers, 65% of whom are Black. Civil believes she’s providing women in her community a way to improve their lives by placing control of their family size in their own hands.

The story unfolds in dual timelines as Perkins-Valdez weaves between the ‘70s and 2016, when Civil is telling her adopted daughter about the long-term devastation her involvement with the Williams family had wrought. While taking a road trip back to Montgomery to visit key players in the case, Civil relays this history to her daughter hoping to relieve the burden of guilt she has carried for four decades.

Rewinding to 1973, Civil observes her supervisor, Mrs. Seager, bullying clinic patients into permanent sterilizations but doesn’t challenge her boss. “Back then all we knew was that we had a job to do,” she recalls. “Ease the burdens of poverty. Stamp it with both feet. Push in the pain before it exploded. What we didn’t know was that there would be skin left on the playground.”

Despite her belief in their mission, Civil is apprehensive the first time she visits patients in their homes and administers injections of Depo-Provera, a hormonal contraceptive. Thirteen-year-old Erica and 11-year-old India Williams seem too young for the drug. They’re not sexually active and live in isolated, rural poverty with their father, Mace, and grandmother, Patricia.

When Civil discovers the birth-control injection is not FDA approved and hears rumors it causes cancer in laboratory animals, she grows alarmed. She recognizes scary parallels between treating her clinic patients with an untested drug and the 40-year Tuskegee University study of untreated syphilis in 600 Black men that was exposed in 1972. Fearful her young patients are guinea pigs, Civil discontinues administering the shot to Erica and India and indicates she has switched the girls to the pill on their charts. But she has not.

Civil tries to right the wrong she inflicted on the Williams girls by inviting herself into their lives. Seeking to lift them out of their subpar living conditions, she notes, “it was hard to keep things tidy with a dirt floor, hard to maintain dignity in a urine-soaked hovel,” and petitions the state for subsidized housing in town for the family.

Through the relationship Civil forms with each member of the Williams family, Perkins-Valdez does an exceptional job of demonstrating how do-gooders can ultimately disrespect poor people out of their own choices by pressing their ideals upon those in need.

Mace is a hard-working widower struggling to feed his family. Patricia is a proud grandmother doing everything she can to ensure her granddaughters are safe and cared for. They have been caught in a cycle of poverty that is hard to escape and, on the road to receiving a hand up, face derogatory treatment and prejudiced assumptions about their capabilities and character.

While Civil immerses herself in improving the lives of the Williams family, Mrs. Seager gets wind that the sisters are no longer on birth control. Without explaining her intentions or receiving permission from Mace or Patricia, she subjects the girls — now 14 and 12 — to permanent tubal ligation surgeries.

Civil is horrified that Erica’s and India’s rights to choose their own lives has been annihilated and seeks legal counsel to ensure it never happens again. What unravels during the subsequent investigation and trial is a national conspiracy of forcing disadvantaged women of color to terminate their reproductive capabilities. From Hispanic women in California to Black women in the Southern states to women in asylums across the country, in a few short years more than 150,000 low-income women receiving assistance were sterilized under federal programs.

In the wake of the Tuskegee syphilis experiment, Senator Ted Kennedy forms a subcommittee investigating federal oversight of healthcare-related abuses and, now at the center of a media storm, the Williams family is invited to the capitol to share their experience.

Increasingly aware of how her overstepping contributed to the girls’ sterilizations, Civil worries the trip will subject the family to more harm, that they “would travel to Washington, D.C., for the fancy politicians to stare and make a spectacle of country Alabamans.” But in the end, their efforts make a difference.

Perkins-Valdez does not offer easy answers to the complex and layered issues of how to best serve disadvantaged people. Instead, she demonstrates a multitude of ways the harmful and helpful ramifications of assistance can impact their lives.

Ultimately, Civil comes to realize, “I am part of the problem. I was in their lives making decisions that weren’t mine to make. Sure, I had good intentions … But good intentions could be just as destructive as bad ones.”

FICTION

by Dolen Perkins-Valdez

Berkley

352 pages, $27

About the Author

The Latest

Featured