Historical fiction is such a powerful tool for getting at the truth of a subject that nonfiction just can’t touch. Even when spun into a compelling narrative, a nonfiction account of an era long past can be informative and enlightening, but it can’t bring history to life the way a well-researched, well-crafted novel can.

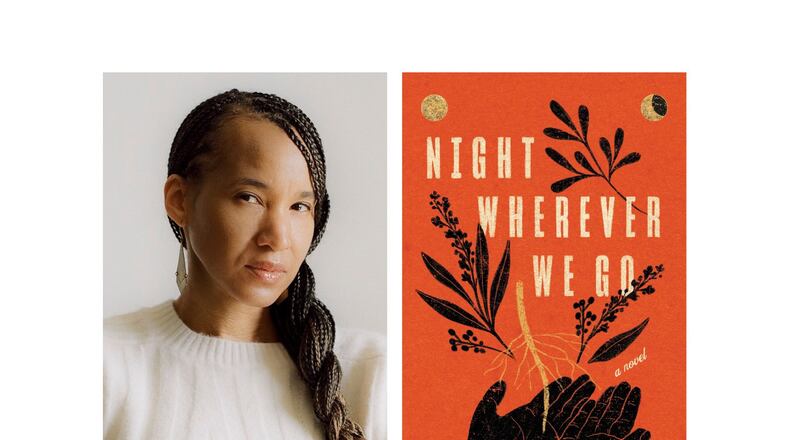

Case in point, Tracey Rose Peyton’s debut novel, “Night Wherever We Go” (HarperCollins, $27.99). If you read just one book for Black History Month, make it this one. Peyton has created a riveting, intimate portrait of six enslaved women thrust together on a struggling plantation in Texas where they spar and bond in their mutual struggle to survive and thrive under desperate conditions.

Harlow is a plantation owner determined against all odds — and there are many — to grow cotton in the “land of wheat.” And his wife Lizzie is none too happy to have been uprooted from her home in Georgia to live in Texas, which “was still new, only a few years old in the Union.” Collectively they and all white people are referred to by the women as “the Lucys” — short for Lucifer.

Acquired from different places and under different circumstances, the women share little in common besides enslavement.

“None of us the same age or born in the same place. Some of us knew the folks that birthed us and some of us didn’t. Some of us were born Christians, others came to it roundabout, if at all. Some of us practiced Conjure and practical magic, others steered far clear. Some of us had born children and lost them, while others were little more than virgins,” Peyton writes.

The oldest is Nan, a maternal healer, midwife and cook. Impulsive Serah is the youngest. Patience is separated from her husband and clings to her young son, Silas, who is being groomed as a “house boy.” Junie grew up as Lizzie’s personal attendant and was forced to leave her children behind in Georgia. Alice spreads misery wherever she goes. And Lulu is a lost soul who’s been sold so many times she steals and lies just to feel connected to something.

At the heart of “Night Wherever We Go” is the evolving relationship between these women who spend their days together cooking, cleaning, sewing, weaving, planting and harvesting. Then at night they sneak out of their cabin to gather in the woods beneath an oak tree — a bucket tipped upside down at its base to “trap the sound” — where they talk about their travails.

Harlow’s failure as a farmer causes tensions to simmer, and the women’s status as commodities is rendered in sharp relief. Alice is sold to pay for a new plow. Lulu and Selah are mortgaged for a time. Slaves from other plantations are rented, as is a wet nurse to feed Lizzie’s new baby.

Then Harlow comes up with a depraved money-making scheme. He’ll hire Zeke and have him impregnate the women, then sell off their babies for profit.

But these women are too wily and defiant to go down without a fight. They put their knowledge about natural remedies to work and begin ingesting cotton root to prevent themselves from conceiving. To their relief, it works.

For a while life goes on. There are some tragic losses along the way, but also fleeting moments of joy. Some of the women attend Saturday night frolics — secret parties held in the wee hours attended by slaves from all around the county. For one brief moment, they get to put on their best clothes and listen to music, dance and socialize. Counseled by Patience on the rules of courting, Serah quickly falls in love with Noah, who returns her affections.

But Harlow will not be deterred in his efforts to force the women to procreate, and he comes up with a new plan that threatens to derail Serah and Noah’s plans. Meanwhile, someone is setting fires across the county, and Lizzie zeroes in on a target for her mounting rage.

There’s no way to truly comprehend the life of enslaved women in the American South during the Civil War, but Peyton’s captivating novel lights up the imagination in a way that leaves you with a better understanding of the horrors they endured. Black History Month or not, this book should be at the top of your to-be-read stack.

Suzanne Van Atten is a book critic and contributing editor to The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. Contact her at svanatten@ajc.com.

About the Author

The Latest

Featured