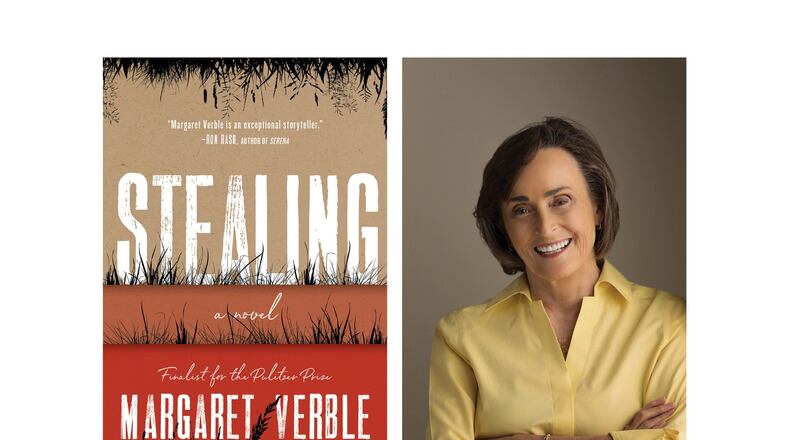

Pulitzer-Prize finalist Margaret Verble’s fourth novel “Stealing” is an historical fiction about a young Cherokee girl in the Midwest who is removed from her family and placed in a residential school in the 1950s. Verble wrote this tender and eye-opening tale in 2007 but didn’t find a receptive audience until the First Nations boarding school scandal in Canada broke in 2021. With a fresh social context in place to frame her narrative, Verble has delivered a nuanced yet powerful examination of the impact of forced Christianity on the indigenous population. And what a story she tells.

Karen “Kit” Crockett narrates her own tale through a diary she’s writing while interned at the fictional Ashley Lordard Children’s Home. She weaves back and forth through time, starting at age 6 after the death of her mother and revealing how she came to be removed from her father’s custody at age 12. Instead of being sent to live with her Cherokee family, who are desperate to care for her, she’s placed in a boarding school so she can “get some education and good moral values.”

Six-year-old Kit is a heroine to root for and her fire does not diminish as she comes of age. Verble has crafted an intelligent and inquisitive child whose precociousness is, refreshingly, not obnoxious. She’s a kid who, while playing checkers against herself, is asked if she’s winning and replies, “Yep. Hard not to.” When informed her Cherokee family is being put under a microscope to determine if they can keep her, she says, “that’s used to look at germs. My family isn’t germs.” Her ability to cut through the adult gaze to see the world as it is lends remarkable strength to Verble’s spare prose and is ultimately what makes Kit so endearing.

Living alone with her father, Kit is a child who catches and fries her own fish for supper. Her father isn’t neglectful, however, and Verble takes particular care to portray Jack Crockett as a grieving widower doing his best to protect those he loves. Kit craves maternal affection and it doesn’t take long for her to attach to Bella Bowing, a pretty lady who moves down the lane. They form a special bond that’s healing for Kit. But Bella draws the ire of the town busybody, and it’s through their entanglement that Kit’s world is blown apart.

“Stealing” is a relatively short book that packs a targeted punch. Verble’s writing is cohesive and thematic, each element utilized for maximum effect. Jack provides a stunning example of how many points of impact one person can make. He’s a white descendent of Davy Crockett and a war hero who possesses less power in society than men who did not marry Cherokee women.

Jack carves a wooden army of miniature frontiersmen for Kit, providing an obvious link to his ancestors. As the narrative progresses, Verble uses the figurines to draw a compelling parallel between Jack’s actions and how his military training sits in stark contradiction with how he is expected to behave in polite society. Impressive, but Verble is just getting started.

Once dad and daughter are separated, the lone frontier figurine that Kit is able to reclaim provides a physical tether to her dad and becomes a source of comfort that only expands once she is sent to Ashley Lordard. The conditions in the boarding school are intolerable and Kit relies on the figurine for advice, developing a symbolic relationship with it as a way to draw on her father’s wisdom. The impact is full-circle and beautiful and a technique Verble employs with regularity throughout the narrative. It’s dazzling to watch her dig into the multiple layers of the title “Stealing.”

When Rev. Cunningham inserts himself into Kit’s situation, wielding his influence to push for her internment at Ashley Lordard, Kit describes him as a man “willing to close his fist on that bird and snuff its life out for no reason except to look wise and in control.” She encounters this type of man again in Mr. Hodges, the director of Ashley Lordard. Both use Christianity to justify committing unconscionable abuses.

Kit displays just enough fight to maintain her sense of self but not too much to condemn her to a worse fate. When she blurts out in the middle of class, “Is this a boarding school or a prison?” Kit knows Mr. Hodges is going to administer a vile punishment. But to not fight back at all would erode her identity in worse ways.

Verble does not use trauma to provoke shock, she uses it with deftness and delicacy to convey struggle. The result is a respectful exploration of survival, not victimhood. By the time the severity of Kit’s mistreatment unfolds, Verble has shaped her into a fully realized human. The care she takes to cultivate Kit’s character pays dividends.

“Stealing” is a masterclass in storytelling, an evocative and accessible exploration of American history that does not deliver a screaming statement on the impact of forced Christianity on the Indigenous population. Until it does. But by the time the message arrives, it’s not received as a lecture but with relief in the knowledge that the characters have a grasp on the bigger picture of their realities. Margaret Verble has harnessed the art of how to shoot straight to the heart of a story, and it is an experience that should not be missed.

FICTION

“Stealing”

by Margaret Verble

Mariner Books

256 pages, $30

About the Author

The Latest

Featured