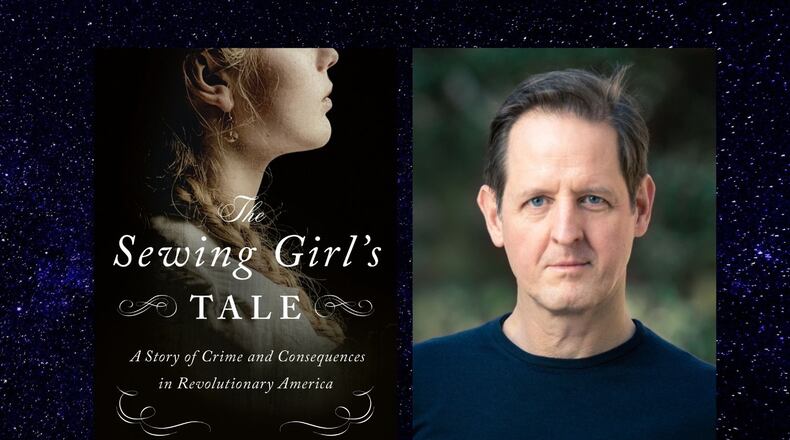

“The Sewing Girl’s Tale: A Story of Crime and Consequence in Revolutionary America” by North Carolina author John Wood Sweet is a probing work of historical nonfiction that exposes the gritty details surrounding the first published account of a rape trial in the United States. Set against the backdrop of a vibrant and burgeoning New York City fresh off the win of the Revolutionary war, Sweet’s narrative combines meticulous research with his extensive historical expertise to recreate a true-crime examination of the sexual duplicity inherent in early American society.

On a blustery summer evening in 1793, a 17-year-old seamstress named Lanah Sawyer was strolling down Broadway when a group of rowdy Frenchmen began lobbing catcalls and insults. A charming young gentleman — distinguished by his walking stick and bouffant of powdered white hair — calling himself “lawyer Smith” intervenes and walks her home. His request to see her again leads to a follow-up encounter that alters both of their lives.

Lawyer Smith is actually Henry Bedlow, a member of the privileged elite who already has a sordid reputation as a “very great rake.” He targets Sawyer — a virtuous young woman from a respectable, working-class family — for a popular seduction scheme designed to rob her of her chastity and annihilate her respectability. Had she known his true identity, Sawyer never would have agreed to a stroll through the park with him a few nights later. She never would have been forced down a dangerous street and held captive by Bedlow in a “bawdy” house of prostitution. And she never would have had cause to file the first sexual assault complaint against a “gentleman” in the United States.

Sweet asserts in the acknowledgments that he’s used the 1793 newspaper account of this story in his curriculum as a history professor at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill for decades. It wasn’t until 12 years ago when he became aware of Lanah’s supposed retraction of the rape charge, printed in a New York newspaper five years after the trial, that Sweet began to research what truly happened.

To present an accurate depiction of Lanah’s reality, Sweet paints a detailed portrait of America’s 18th century moral temperature. Lanah is “genteel enough to value a reputation as modest, respectable, and sexually innocent yet obliged by necessity to work to help support her family financially.” A mark of impurity on Lanah’s reputation meant social ruin, not just for her but her household. Yet her walk to work allows for encounters like those with the Frenchmen and Bedlow. This conundrum is the first of many social impracticalities Sweet scrutinizes through the lens of Lanah’s tribulations.

Bedlow’s defense team accuses Lanah of “crying rape” to shield her character from defamation. His six lawyers admit a seduction occurred but maintain Lanah consented, then later regretted her decision. They proceed to slander her during hours of grueling courtroom testimony for daring to associate with a man above her station. Like many modern sexual assault cases, the trial becomes more about the victim, and society’s perceptions of her morality, than evidence of the perpetrator’s guilt.

The expertise Sweet gained as director of sexuality studies at UNCC lends him the authority to address the impact of acquaintance rape. He argues, quite effectively, that Lanah’s behavior following Bedlow’s assault is consistent with current psychological understandings of rape survival. But in 1792, Lanah’s immediate actions were her undoing. Rape laws were still sprouted from Sir Matthew Hale’s strict British criteria valuing a woman’s reputation, and the impressions left by her behavior, over physical evidence. Hale’s objective was to thwart “malicious women (who) might bring false rape charges against men of property and good standing.”

As men of wealth and influence still do, Bedlow uses his privilege to armor himself against consequences. But Lanah’s father is an unexpectedly worthy opponent. He holds an influential position in working-class society and wages a battle that last for years against Bedlow to restore his family’s reputation. Their conflict grows to consume popular interest quite a few times. At one point the outcry results in street riots and later in a series of scathing letters published in the newspaper that would put a modern-day Twitter war to shame.

Yet this was never Lanah’s fight, it was her dad’s. She was her father’s property, therefore legally he was the party who was injured by Bedlow’s assault. This is one of several situations Sweet uses to illustrate how men take over Lanah’s narrative, repetitively reducing her as they use her experience to further their own agendas. Another way Lanah becomes diminished is by the startling lack of a record of her outcome. Post court transcripts, there is no physical evidence of where she goes or what she does. Was she even the author of the letter retracting her rape that was published five years after the trial?

Sweet takes meticulous care not to usurp Lanah Sawyer from her own story. Instead, he produces a historical retelling that is decidedly pro-woman, highlighting a multitude of ways working-class females were held to an impossible standard of propriety. And by comparing 18th century mores with the ethos of today, he slams a gavel on the lack of progress society has made in 230 years regarding victim-shaming, abusing privilege and the female double standard.

“The Sewing Girl’s Tale” delivers a fascinating dive into history while restoring Lanah’s place in her own narrative. Sweet even argues that Lanah’s disappearance into the mist of time could be how she reclaimed her autonomy. Once she was no longer available to be exploited, his hope is she found peace in her anonymity.

NONFICTION

by John Wood Sweet

Henry Holt and Co.

384 pages, $29.99

About the Author

The Latest

Featured