The accelerating drumbeat about reinventing schools after COVID is like greeting the ashen survivors of a capsized boat as they crawl to the shore with, “Your backstroke really needs improvement.”

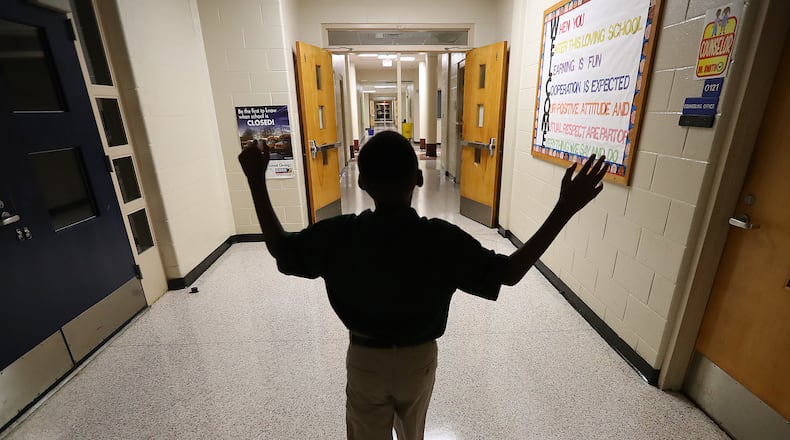

The COVID classroom — virtual or in-person — tested schools and educators like never before. Celebrated for an agile leap from face-to-face classes to remote instruction a year ago, teachers then found themselves condemned for hesitancy about returning to buildings amid the conflicting science around infection.

Now, education analysts, philanthropists and advocates — many of whom spent the past year and a half working from their living rooms far removed from the classroom challenges of COVID — have laid out ambitious goals for schools that leave little room for rest or recovery.

I am not convinced anyone in a classroom has the energy for reinvention right now. Many parents, teachers and students seem to want to return to what they left behind in March of 2020 when COVID-19 shuttered schools.

“I think most parents want the world to snap back to normalcy, and a big part of that is kids going back to in-person schooling,” said labor economist Dan Goldhaber, director of the Center for Analysis of Longitudinal Data in Education Research at the American Institutes for Research. “My personal opinion is we ought to take advantage of this tumultuous year and see what information we can learn on how we can do school going forward.”

But Goldhaber cautions against imposing new expectations on classrooms and teachers. “If we are talking about anything that requires implementation at the individual teacher level, then I think this is probably a bad time to ask teachers to do yet one more thing.”

Teachers and students need a chance to reset and to reflect on the experiences of the past year, said Lisa Morgan, president of the Georgia Association of Educators. “We met with a group of educators Monday night, and they all said there may be things they learned from this year that they will use, but they need time to decompress and really think about what they did this year, what worked and what they might carry over.

“What we’re hearing about reimagining education is truly coming from those with the very best of intentions who believe there are things we can learn,” said Morgan, a classroom teacher for 21 years. “Educators believe that as well. However, for those educators who have been in the classroom, the tired they feel this year is different than it has ever been. One of the things that has been overlooked is the mental exhaustion of educators, students and parents.”

But there is some reimagining that would not burden teachers, said Goldhaber in a telephone interview. “Every state waived a number of employment eligibility criteria for teachers during the pandemic. There is a lot of debate over some of those criteria, like licensure tests. It would be a pretty radical change if states shifted what is expected of people who want to enter the labor market.”

Calls to restructure schools intensified after President Joe Biden announced an unprecedented investment of $122 billion in education from his $1.9 trillion American Rescue Plan Act, $2,440 for each of the nation’s 50 million students. Georgia’s share is $4.25 billion, of which $3.8 billion is going to districts.

Those billions shifted the conversation from how COVID upended American classrooms to the opportunity afforded now to restructure education. At the same moment in which states and districts are being asked to reimagine the fall and beyond, they remain overwhelmed with the nuts and bolts of getting students back into school and then planning out the summer.

The theme of reinventing and reimagining schools was repeated by dozens of panelists at last week’s Education Writers Association National Seminar. “For us, it’s really about thinking about what September is going to look like, what’s going to be different for us, and really blowing up what we think of as education,” said Angélica Infante-Green, Rhode Island commissioner of education.

States that have already begun end-of-the-year testing, including Georgia, have another item on their to-do lists — dissect their assessment data to see where students are and what they need. The needs are likely to be considerable.

Based on testing from September and October, Emma Dorn, global education practice manager at McKinsey & Company, said the school shutdown in March of 2020 caused students to begin this school year about six weeks behind in reading and three months in math.

“Now, districts and states did an awful lot of work over last summer and are continuing to work to improve remote learning, getting some students back to school safely,” said Dorn. But even assuming that remote classes were enhanced, learning losses in math could be significant, she warned.

An analysis of the pandemic’s impact on student academic growth by the Georgia State University Metro Atlanta Policy Lab for Education released today found similar results, although the learning losses across the districts were not uniform.

“We can’t minimize the importance of this loss,” said Dorn. “The average student would lose $60,000 to $80,000 of lifetime earnings with seven months of missed math learning. That means some students won’t graduate high school, go to college, won’t get a job that enables them and their families to thrive.”

While the U.S. has long grappled with learning gaps, Dorn said, “We’ve never dealt with a crisis that has hit every single student in the whole country. Learning disruptions have been substantially worse for Black, Hispanic and low-income students, which is really worrying in terms of widening preexisting gaps.”

There was agreement the pandemic has taken a toll on teachers. “Teachers need a break,” said Dorn. “And yet this very moment is the time where we want to run summer school and we want to run tutoring programs. How do we expand the aperture on the human capital that we can bring in to help students?”

Exhaustion represents the greatest obstacle to school reinvention, said Rhode Island school chief Infante-Green. “Everybody’s exhausted. The hardest part is really pushing ourselves to go to the next level and not continue to do things as we’ve done, but really having a strong campaign where we energize the community, the parents, the teachers, everyone.”

About the Author

The Latest

Featured