Matthew Boedy is an assistant professor of rhetoric and composition at the University of North Georgia and president of the Georgia Conference of the American Association of University Professors. In a guest column, Boedy writes about his recent Twitter debate with American billionaire entrepreneur Mark Cuban on higher education today and how it needs to change.

By Matthew Boedy

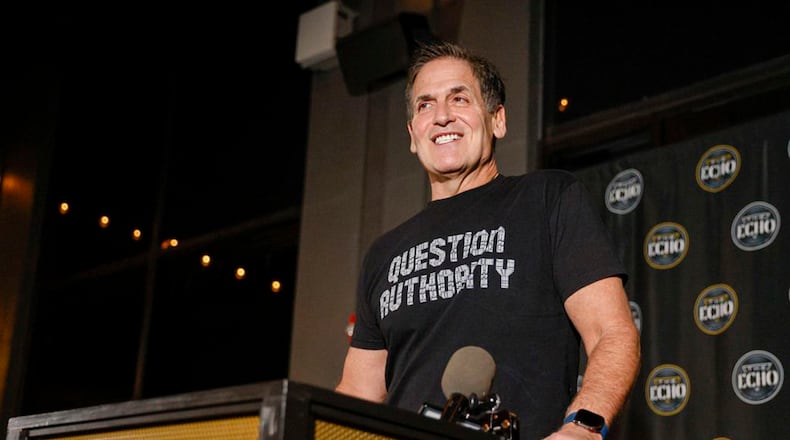

Mark Cuban was kind enough to converse with me on Twitter recently. Yes, that guy: Dallas Mavericks owner, “Shark Tank” star and disruptive philanthropist with 8.6 million followers.

I say kind enough because my initial reply to his tweet about the cost of college was snarky. I implied he didn’t know what he was talking about concerning how higher education worked.

But after noting that was his point — that our system doesn’t work — we had a considerable back and forth on this important topic.

I won’t rehash every word of what we said. You can try to follow the thread. I want to give you the main points because it’s a good conversation to have across dinner tables, along voting lines and in classrooms.

Credit: Peggy Cozart

Credit: Peggy Cozart

Our discussion began with Cuban’s attempt to imagine a higher education disruption that could bring down costs, which we all can agree are too high for students, families and alumni still paying off loans.

Cuban sees two main reasons for the high price: inefficiency and what he calls “frills.” We might assume we know what those are but, sadly, he didn’t define them.

In short, what Cuban is after is a low-cost school. It’s not a new concept in higher education. And it’s a concept bound to get more eyeballs from lawmakers and state overseers, such as our Board of Regents. Our state, like so many others, faces what experts have called an enrollment cliff — a stark reduction in the number of births and so opportunities for enrollment. And, of course, complaints about student loans and tuition are a bipartisan talking point.

Cuban admitted in our conversation that “the hard part of my idea is defining what a low cost school should look like. Like hospitals, schools tend to emphasize reputation and scale over efficiency. They market to 18-year-olds and their parents because they have to and that distorts their educational efforts.”

That marketing, as I pointed out, includes the elements that make up the college experience all students want, such as sports. I doubt Cuban sees those as frills. He might want to eliminate snazzy dorms and other aspects of campus life that in his mind distort the education aspect. (By the way, there are two other central purposes of higher education that he is ignoring: research and service.)

If you know Cuban’s story, one might think he is interested in merely scaling up his own college experience. He chose Indiana University without looking at the campus because it had the lowest tuition. He took night courses at Pitt before that. Certainly, no frills in that experience.

Cuban, though, is not just interested in remaking one school. He is interested in disrupting the system by using one school to create competition among all in the same state or region, which he tweeted about.

In short, Cuban thinks this idea could bring about the efficiency missing today in higher ed.

I mentioned to Cuban that Georgia would be a good place to see if his ideas have merit. Amid a new chancellor and remade Board of Regents, Georgia faces challenges, including that nationwide enrollment cliff. Some of our public colleges are already hemorrhaging students — not to mention the growing culture war on education.

Cuban contends we may have too many four-year schools. I tried to persuade him of the need for diverse types of schools like we have in Georgia. We all understand the University of Georgia and the University of North Georgia don’t compete for the same students. That is a good thing.

Competition among schools might bring us a market winner, but the community that a school is grounded in would lose. For example, if the University of West Georgia battled with UNG and one was forced to close, the college-less region of our state would be a higher education desert. And if that plays out across the state after a future round of consolidations, we might be left with only a handful of mega schools.

Why is such a desert bad?

The question reveals my larger assumption that the business mindset that made Cuban millions doesn’t fit higher education.

And so far, our state’s leaders agree with me.

Our Board of Regents is filled with business owners. They have brought business to campus in many ways, some terrible. But they have not yet gone full Cuban. They have tinkered here and there with degree programs designed for specific industries. Before the pandemic, the board was about to change the system’s core curriculum based on input from business leaders.

But they also know the importance of a college campus to a community. They each want a school (or two or three) in the area they represent that produces successful alumni who donate and instills a sense of accomplishment in as many students as possible who can return to their hometown and be productive citizens.

While none of us can ignore waste or corruption, we should spend tax dollars on the college experience because that experience sells the value of college as much as the education gained. We can debate what constitutes frills and what is essential.

What we shouldn’t debate is the communal impact of higher education. If we all can agree on that, then there is one easy solution to trying times for tuition. Return to a time when state funding for higher education outnumbered student loans by millions.

About the Author

The Latest

Featured