Miriam Udel directs the Tam Institute for Jewish Studies at Emory University and is a scholar of children’s literature and its political import. In this guest column, Udel commemorates the upcoming 80th birthday of Mildred D. Taylor, award-winning author of “Roll of Thunder, Hear My Cry” and eight other historical novels for young readers about Mississippi from Reconstruction through the Jim Crow era.

Udel highlights Taylor’s work as a resource for families seeking to educate our children about Southern racial history with nuance and truth, especially in light of increasing efforts to ban children’s books in libraries and school curricula.

By Miriam Udel

I had been living in Atlanta for just a couple of years when I found myself stuck in traffic on a morning school run, stopping and going next to a yellow school bus full of waving, gesticulating children in high spirits. My kindergartner’s voiced piped up from the back seat to ask, “Why are all the kids on the bus Black?”

I mentally inventoried white flight and redlining, groping for how to explain the roots of residential segregation or at least preserve the question until he was old enough to tackle it in simple terms.

I believe we love children best when we tell them the truth about the world, and I knew I would need help telling my son and his baby brother the truth of how racial history pulsates all around us, conditioning our lives — of how the so-called past, in William Faulkner’s memorable formulation, isn’t even past.

As a scholar of children’s literature, I know that shared reading and discussion with a trusted adult can help children confront emotionally fraught topics, building empathy and a sense of self-efficacy in the service of justice. To answer my son’s innocent question, I would need to center Black voices while painting a picture capacious enough for him and his brothers to find their place in it as white boys growing up in a 21st-century family newly transplanted to the American South.

Credit: Shulamit Seidler-Feller

Credit: Shulamit Seidler-Feller

I used the work of novelist Mildred D. Taylor, who turns 80 on Sept. 13, just a couple of weeks ahead of Banned Books Week, to anchor my children’s “home training” in Southern history and inform how we discuss race and the persistence of racism. Her work bends as far as possible away from the misbegotten, fundamentally dishonest approach, idealized by many, of teaching children “not to see race.” Taylor’s unflinching eye and insistent realism make white readers productively uncomfortable. Passages that make us wince or tear up are the emotional cracks where the light gets in, and they ought to invite conversation, not suppression.

According to efforts at tracking banned books by both the American Library Association and the literary advocacy organization PEN America, increasing numbers of parents, legislators and other stakeholders believe that their discomfort with challenging content — whether connected to race, sexuality, abuse, health or death — ought to dictate censorship of those books for everyone’s children. In 2022, the ALA recorded the highest number of banning attempts since it began monitoring them 20 years earlier.

The ethos of “just letting children be children” doesn’t work for youngsters whose communities have been subjected to historical violence and are likely to still face elevated risk of hate-based harm. If some children cannot afford to remain innocent of racism, antisemitism, homophobia and other forms of marginalization and bigotry, then neither should their peers.

To condemn children to ignorance, masquerading as innocence, is a particularly insidious form of majority entitlement. Being Jewish sensitizes me to these dynamics but hardly exempts me from reckoning with the degree of white privilege I hold, however partial or conditional.

Parents of all racial backgrounds have attempted to exclude Taylor’s books from libraries and curricula for decades, hoping to protect children from images of harm and wounding racial epithets. “Although there are those who wish to ban my books because I have used language that is painful,” writes Taylor, “I have chosen to use the language that was spoken during the period, for I refuse to whitewash history. The language was painful and life was painful for many African Americans, including my family. I remember the pain.”

Like many award-winning authors whose work is both celebrated and frequently banned, Taylor has a finely honed sense of what children can handle emotionally and how to scale her candor to readers’ developmental readiness.

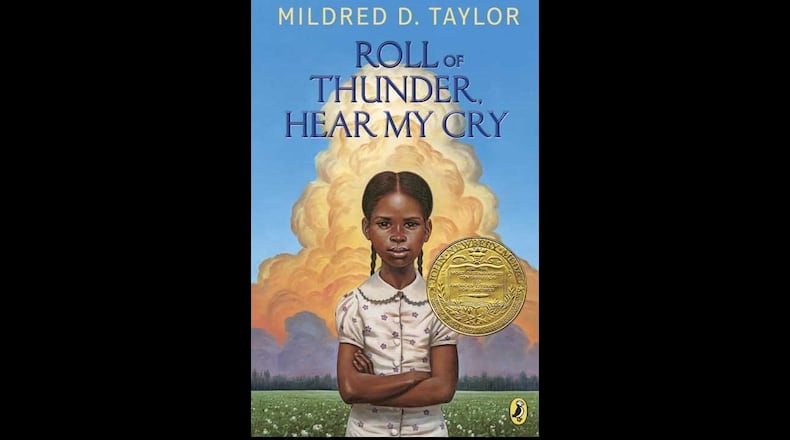

Re-encountering Taylor as a mother felt like meeting an old friend. Beginning in the third grade, I had read and reread her best-known novel, “Roll of Thunder, Hear My Cry,” a book I cherished alongside titles by Judy Blume and Paula Danziger as missives from the few adults who would speak plainly about matters that we kids could dimly perceive in a grown-up’s grimace or helpless shrug. Cassie Logan is one of those protagonists we hate to part from at the end of a book, and I was thrilled to discover in adulthood that I didn’t have to: Taylor published nine novels and novellas between 1975 and 2001, many of them centered on the loving, dignified Logan family.

There are prequels, sequels and spinoffs, and I read each one aloud with my middle son. My youngest child will hear or read them around age 10 or whenever he takes an interest in the volumes encased in vibrant, inviting cover art by Kadir Nelson and the late Jerry Pinkney. These are books for children and adults to read — and savor — together.

As we watch Cassie grow from spirited elementary schooler to watchful, reflective adolescent under a regime of racist terror, we also witness Taylor’s subtlety in crafting richly layered plots that interweave the precarities of race, class and gender. Drawing on her father’s stories of her own family’s past, Taylor presents harsh events with sensitivity. Night riders and burnings are kept at the periphery, an attempted lynching is foregrounded but averted by the quick thinking and selfless sacrifice of Cassie’s parents. Taylor illustrates the mechanics of how old-money planters cynically employ fear of “dangerous” race-mixing to preserve their own place at the apex of the economic pyramid, to the detriment of all others. Ultimately, these stories awaken in readers a sense of hopeful urgency rather than nihilistic despair.

The would-be censors are onto something though. Taylor’s books and other “challenging” works on banned lists demand a level of adult engagement that more anodyne titles might not. In catalyzing uncomfortable conversations, this work is a gift to those of us who wish to raise our children not to avert their gaze from history and its present legacy.

Despite the loud voices of the would-be censors, we appear to still account for the vast majority of American parents. A 2022 poll commissioned by the ALA indicates that 71% of voters nationwide, across the political spectrum, oppose efforts to have books removed from their local public libraries. Librarians, teachers and most American parents understand that if children could live the realities that Taylor depicts with such nuance and fierceness, then our children can — and must — learn about them.

About the Author

The Latest

Featured