A degree and a dream deferred: Chance meeting corrects a half-century wrong

As one of the first Black students at Mercer University, Gwendolyn Middleton Payton hoped to study biology and medical illustration when she began in 1968.

A Macon native, she knew the Mercer campus well. She belonged to the inaugural class of Upward Bound, a federal anti-poverty program launched in 1965 by then-President Lyndon Johnson to spur college attendance by bringing low-income high school students to college campuses through summer classes and programs.

Then, as a freshly minted college freshman, Payton was excited to visit the art department to seek guidance. What she got was contempt. “The department head was in his office and confronted me about being in his department. He literally told me ‘negresses’ were not smart enough to get a degree from his department.”

The insult neither shocked nor shattered her. Payton had heard it before. Three years earlier, her mother, Johnnie Mae Middleton, learned that A.L. Miller High School, an all-white and all-girl public high school in Macon, was going to integrate and decided to enroll her.

Payton balked. She was one of nine children. Her three older siblings attended the African American high school, and she was looking forward to being with them.

Her mother, who had only finished the seventh grade and worked as a hospital nursing assistant, wanted Payton to go to college, and felt Miller High School could help. At a meeting with African American students considering transferring in 1965, the Miller principal opened with a warning that they weren’t likely to graduate.

“The principal stood up and told us, ‘You people are not going to be able to complete your education. You don’t have the tools to finish,’” said Payton. “My mother made the decision that I was going to attend, and that, no matter what, I was going to finish.”

Payton integrated Miller, graduating in the Class of 1968 with 11 other African American young women. “We all had the resolve that we would finish,” said Payton, who is now 69 and lives in Athens.

So, three years later at Mercer, Payton again summoned her resolve. "Just because the department chair didn’t think I could get a degree didn’t mean I couldn’t do it. I was thinking this will not deter me.”

The racism she witnessed didn’t stop Payton from studying art and exceeding the course requirements for an art major at Mercer. But it did prevent her from receiving her degree in art.

At the end of her junior year, she married her college sweetheart, Victor Payton, who was in the class ahead of her and bound for the U.S. Army and medical school. In the fall of her senior year in 1971, Payton found herself at a tense meeting with the department chair where he declared her portfolio lacking and insisted she was short a course. “He was kind of gloating and told me, ‘I guess you won’t be able to get your degree after all.’

“There were no cellphones so I left that building and ran all the way to the dormitory to call my husband. Victor encouraged me to go back and talk to him. In that second meeting, the department chair dug in his heels and told me several of the paintings I wanted to exhibit were too controversial and he would not allow them,” she said.

Payton hated disappointing her mother, who was always proud of her daughter’s art ability and admonished her other children not to bother Gwendolyn when she was busy with her art. Payton’s father, Johnny Middleton, who died at 56, was a talented artist. But Payton felt the department chair would not bend. She still checked to see if her name was on the list of art major candidates as graduation approached. It wasn’t.

‘Dreamer’ finds an ally

While she graduated from Mercer with a degree in biology, Payton always regretted she never got her exhibit or her art major. She sent a letter to Mercer in 2013 at the prompting of her friend and noted Athens artist Jean Westmacott, but nothing came of the effort. Her husband, Victor, said he assured her, “You are an artist. You don’t need them to tell you that. But that wasn’t the issue; she had earned a degree and was basically denied it because of lies.”

Then came a chance meeting at the Atlanta airport in the middle of the night 47 years later.

That moment led to an exhibition now underway at Mercer of Payton’s paintings, titled “The Faith of the Dreamer: Opposition to the Truth May Derail the Dream but the Faith of the Dreamer Prevails.” With paintings from Payton’s days at Mercer and later works, the exhibit at the Plunkett Gallery in the Hardman Hall Fine Arts Building will run through Oct. 16 and is open to the public.

Sarah Gardner, a Mercer University distinguished professor, was not supposed to be waiting for a shuttle bus outside Hartsfield-Jackson International Airport a year ago at midnight. Her plane out of Edinburgh, Scotland, was late, so she missed her original connecting flight to Georgia from New York.

She was frustrated and exhausted when Payton, just back from visiting her son in California, sat next to her and struck up a conversation. “Gwen clearly had had a good trip. Her mood was kind of infectious. And she put me in a better mood.”

When Gardner revealed she taught history, Payton expressed delight. "There were no women on faculty in the history department when she was a student. She chuckled, trying to imagine what those male professors would have thought about my being in the department. And then she became quiet. And she wasn’t really smiling anymore,'' said Gardner.

Payton told Gardner about never earning her art degree at Mercer, but went on to note that she met her husband at Mercer and she had continued to paint even while raising four children in Athens, Georgia, and working in her husband’s busy pediatric practice.

That a student at Mercer in 1972 experienced racism didn’t surprise Gardner; the American South is among her areas of expertise. But it angered her. “I was raging inside when she told her story. It is clearly a power play; some guy exercising power in the worst kind of way,” she said.

Gardner decided on that airport bench that this chapter of Mercer’s history should be rewritten. “Universities grant honorary degrees all the time. So, why on earth couldn’t Mercer confer a major on someone who actually completed her coursework, save the exhibition she was barred from giving? It seemed to me that we should be able to fix this,” said Gardner.

Gardner began to try the next day, relating Payton’s story during a meeting of the dean’s executive committee, of which she was a member. Dean Anita Olson Gustafson, head of Mercer’s College of Liberal Arts and Sciences, immediately agreed to speak to the registrar to confirm Payton had the courses and credits required for the degree.

“Of course, she did have them. Then, it was a matter of getting the time and space to put on the exhibit,” said Gardner.

“Although Mercer admitted African American students earlier than most other private universities in Georgia and today is one of the most racially diverse private universities in the country, progress was at times uneven,” said Gustafson. “When I learned about Ms. Payton’s story, I verified that she indeed had earned enough hours but only lacked the final culminating project for the art major. I immediately reached out to the Art Department to begin planning Ms. Payton’s show — 48 years later. I am so happy that we were able to turn her dream into a reality. She is a remarkable woman and a talented artist who has never lost faith in what is possible.”

For Victor Payton, the exhibit “eases my long-term hostility to what was going on then and how hurtful it was to Gwen. It also shows that while there are good people around who are concerned, there are only a few who are concerned and also willing to make a difference and that was Dr. Gardner.”

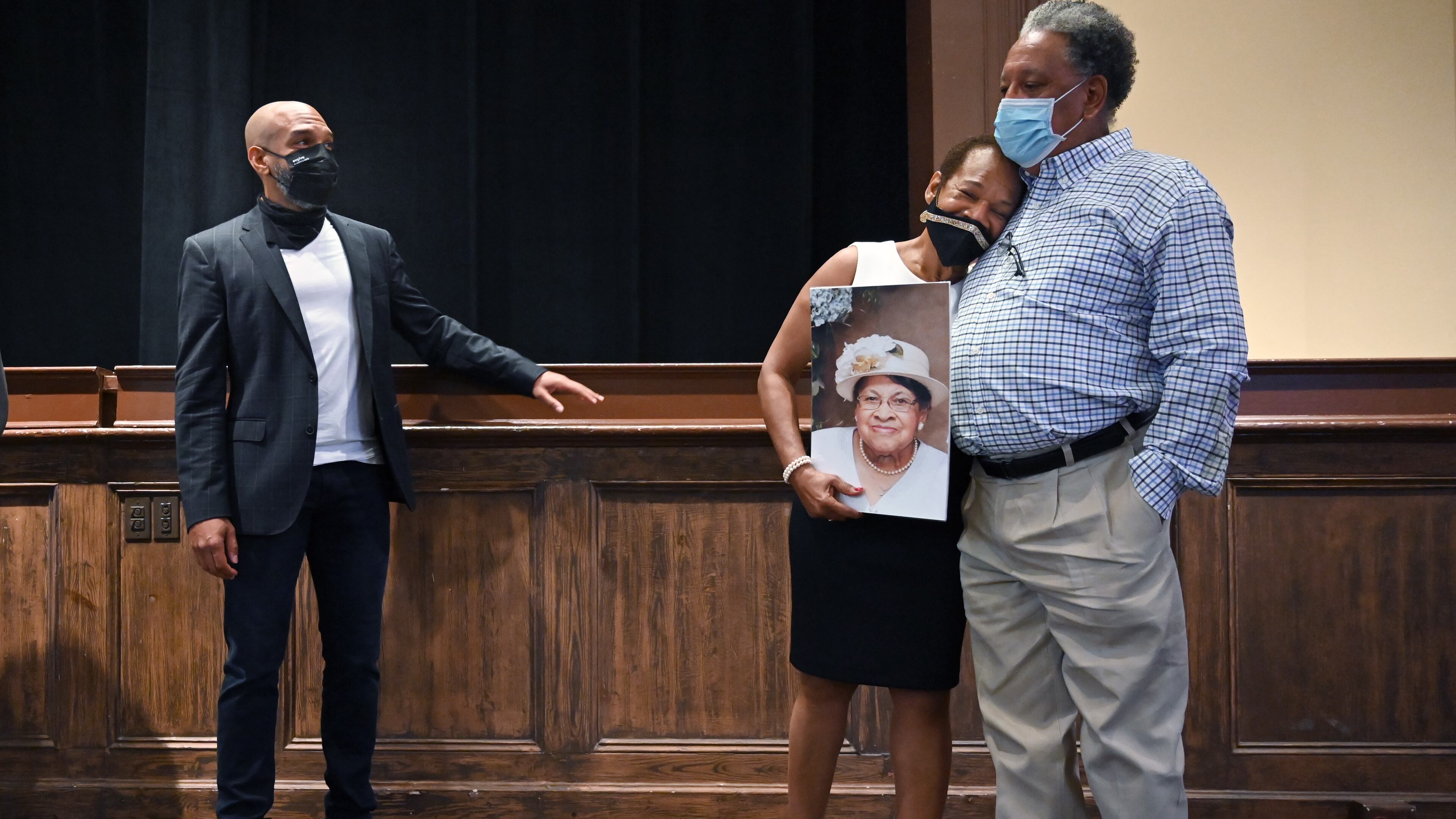

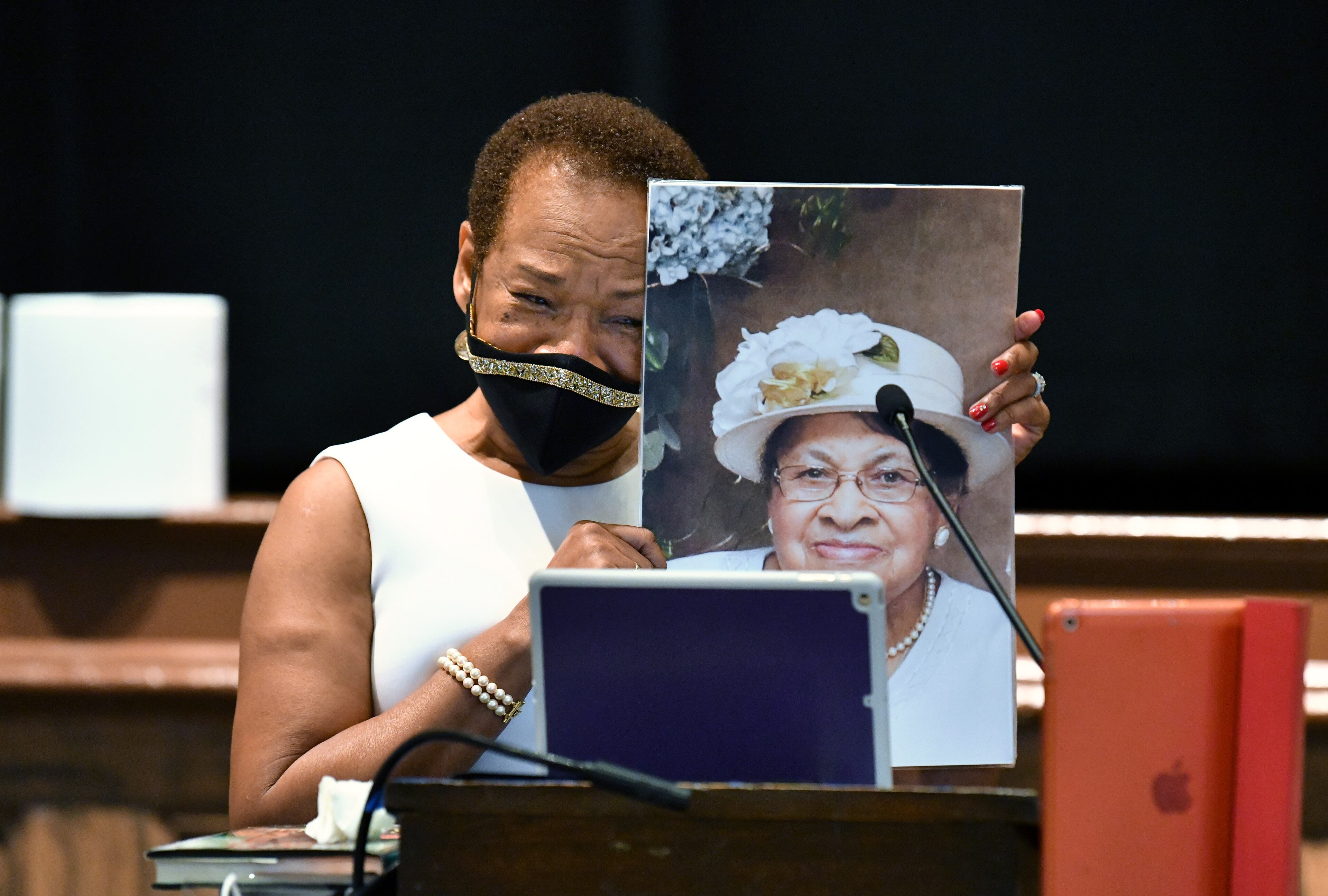

At a ceremony Sept. 25 at Mercer, Payton was awarded her missing major in studio art by Gustafson to robust applause from family and friends. Her story is an amazing story, Gustafson told the crowd. “It is an African American story; a Southern story; a Mercer story; but as a whole, it is an American story. And it is a story of hope.”

“I really cannot believe I am standing here,” said an emotional Payton after coming to the podium. “I have come here today because my heart was always seeking this degree. I thank God for this day. I know that everyone goes through many different challenges in life, but you’ve got to have an inner sense of who you are and that will carry you to where you want to be.”

Struggles and tragedy

Today’s Mercer is a very different place than when Gwendolyn and Victor Payton attended. This year’s freshman class is 51% non-white and 27% are first-generation college attendees. When Payton began Mercer, the university had only admitted its first Black student five years prior. Sam Oni, a brilliant student from Ghana who had been urged to apply to Baptist colleges by Southern Baptist missionaries in Africa, started at Mercer in 1963. The young man had barely unpacked when the pastor of the Baptist church on campus came by to tell him that he would not be welcome at Sunday worship.

Payton and other students on the front lines of integration walked through newly opened doors only to find many opportunities within closed to them. For example, in high school, Payton was a top athlete, practicing with the volleyball, tennis and basketball teams. She never played in any games because she was not allowed as a Black student to travel with the team and compete.

“When you come from a people who have been denied the right to vote, who were still not able to enter the front door of a doctor’s office, you understand all the rules and regulations. At that time, I was not prepared to take a stand about not being able to go with the team. I was there to get an education,” said Payton.

At Mercer, Payton began to push back, playing an integral role in the successful student-powered campaign for a Black studies program. Mercer introduced a Black history major in 1970. “There were other African American students dealing with similar situations with professors at Mercer. On one hand, it was personal to me, but on the other, it was not a battle I could fight when I was trying to get a Black studies department. Most of the African American students who attended Mercer while I was there went on to very distinguished careers. We are a very resilient community of people and there are many untold, amazing stories in our history."

The timing of the exhibit amid the Black Lives Matter movement and public anger over police shootings of Black Americans reminds Payton of the atmosphere in Macon when she was in college. While dealing with racism at Mercer, Payton also lived through a horrific personal tragedy. Her beloved younger cousin Curlen Middleton, whom she had convinced to move to Atlanta to attend DeVry, was killed by a self-described white vigilante.

In November of 1971, Curlen Middleton, 19, had driven home to Macon from DeVry in his new used car for an early Thanksgiving dinner with his mom and younger brother Vernon before traveling with a schoolmate to North Carolina. Middleton, his classmate and 17-year-old Vernon were returning to their neighborhood early in the morning after a quick sightseeing tour of Macon, which included the Mercer campus, when a white man began following them in his vehicle before striking their car from behind.

When Curlen Middleton got out to inspect the damage, the driver shot him in the back, killing him. He also seriously injured Vernon. “My brother saved my life,” said Vernon Middleton, recalling how Curlen pushed him out of the way. To this day, Vernon said he does not know what drove the man to such violence against three teenagers just driving home. “I have no idea what he was thinking at the time, but there are people in this land who cause terror to others without cause and to themselves without understanding," he said.

Senior art students at Mercer have been involved with mounting Payton’s exhibit and have recognized the similar social justice themes linking their world and Payton’s.

“The timeliness — and ugly persistence — of the issue is not lost on them, and I believe the parallels from Gwen’s narrative and some of their own experiences are felt,” said Ben Dunn, director of Mercer’s McEachern Art Center and curator of Payton’s exhibit.

A family’s source of pride, strength

Payton’s son, actor Khary Payton, who is King Ezekiel on “The Walking Dead,” understands his mother’s desire to right a nearly 50-year-old wrong.

“Whenever you work hard for something, you want to celebrate that time in your life. My mother and father met in college. They were among the first to get a chance to go to college, to matriculate at a university that was segregated only a few years before,” he said. "All those milestones are things that should be celebrated. So, if you run the race and they won’t let you across the finish line, it sticks with you.”

Khary Payton said his mother always finds the best in any situation. “When you live in the same house with that kind of sunshine, it sticks to you,” he said. Khary is the oldest of Payton’s children. His brother Kurlen is a physician and interim director of the Division of Neonatology at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles; his brother Kurtis is an engineer with Honda in Marysville, Ohio, and his sister Kalere is a costume designer in Sweden. Payton and her husband have seven grandchildren between the ages of 2 and 11.

Payton’s ability to stay hopeful has been a boon to the family over the past few years as Victor Payton battles a rare form of leukemia. Khary Payton credits his mother’s drive to ''turn the brightness up," along with some innovative doctors, for keeping his father alive well beyond the initial prognosis. The family recently marked the sixth anniversary of Victor Payton’s diagnosis when doctors advised him he had seven to 12 months to live.

He said his mother’s positivity comes out of determined effort. “She has said to me many times that she told herself, ‘I am not going to let this keep me down. I am not going to let this break me.’"

“My mother had an incredible mother who came from nothing but had a vision for her children and was going to see her daughter get ahead. So, when that high school principal told my mother she would not graduate, my mother put a lot more stock in what my grandmother thought than what the principal thought,” said Khary Payton. “At the end of the day, that principal and that art department professor were wrong.”

Gwendolyn Payton’s mother died in April, but she knew the exhibit was coming. “She was incredibly excited about it. Up until the day she passed away, it was one of her most joyous thoughts,” said Payton. “The most important thing to me is that this is a culmination of my life with my mom and her being able to see all her efforts for me brought to fruition before she passed away.”

EXHIBIT PREVIEW

“The Faith of the Dreamer: Opposition to the Truth May Derail the Dream but the Faith of the Dreamer Prevails"

Through Oct. 16. Free. Plunkett Gallery in the Hardman Hall Fine Arts Building at Mercer University, 1400 Coleman Ave., Macon. facebook.com/fspgallery/