Growing up, I had plenty of opportunities to chant "sticks and stones may break my bones, but words will never hurt me."

I've slowed down a bit since those fleet-footed days, but more things bounce off me.

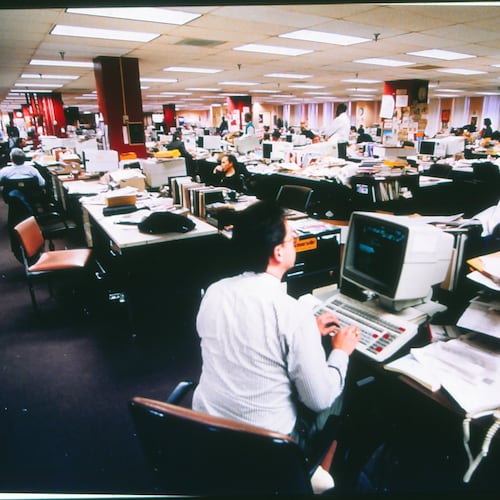

Credit: George Mathis

Credit: George Mathis

Society, on the other hand, is more sensitive. People are hurt by so many things today children can't hope to recite the complete list before the bully catches up to them.

Today, my eclipse-toasted retinas informed me ESPN is pulling an announcer from a college football game in in Charlottesville, Va., because his name is Robert Lee.

"It’s a shame that this is even a topic of conversation and we regret that who calls play-by-play for a football game has become an issue," said the sports network.

Anyone paying the slightest bit of attention will recall Robert E. Lee was the general of the losing side of the Civil War and, unlike the ESPN sports announcer, not of Asian descent.

I'm sad to report we now live in a world where a major network thinks TV viewers might think a Civil War general is announcing a football game and become violent.

What about football players with similar names? I couldn't find an active college player named Robert Lee, but Texas State has a fellow named Sherman. Hopefully no one confuses him with the guy that burned Atlanta.

There are few incidents of statues harming people physically, but I understand why some want the last vestiges of the Confederacy yanked.

Most Confederate monuments were erected long after the Civil War. Initially, some were built in cemeteries to honor the dead. Decades later, as more African-Americans demanded justice, they began popping up at county courthouses.

The United States must lead the world in the number of war memorials the victor allowed to the defeated.

The biggest one of all is at the end of the appropriately named Memorial Drive on the north face of Stone Mountain. Work on the 1.5 acre carving, the largest of its kind on earth, began in the 1910s, about the same time the mountain became the home of a revived Ku Klux Klan.

Georgia has the biggest Confederate memorial, and, according to a recent AJC analysis, the second most after Virginia.

As a boy, I often played around the Berrien County Courthouse. I'd read comic books at the drug store and get an ice cold Coca-Cola for a dime.

The first "Spirit of the American Doughboy" statue is there. It honors the locals who died in a noble cause that was not lost -- World War I. The names on the statue were of boys not much older than me. Many of them, I recall, had the same last names as my school friends.

The doughboy came to town in the early 1920s, shortly after "The Great War" concluded. In 2007, almost 150 years after the Civil War, a "War Between the States" memorial joined it.

"This monument is erected in honor and memory of all Confederate soldiers who defended our constitutional freedoms," the stone says. "All races and religions joined together to defend the Confederacy, their families, their property, and states rights against northern aggression led by Abraham Lincoln."

Those who cannot accept the past are condemned to revise it.

About the Author

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured