Lethal injection secrecy rattles appellate court

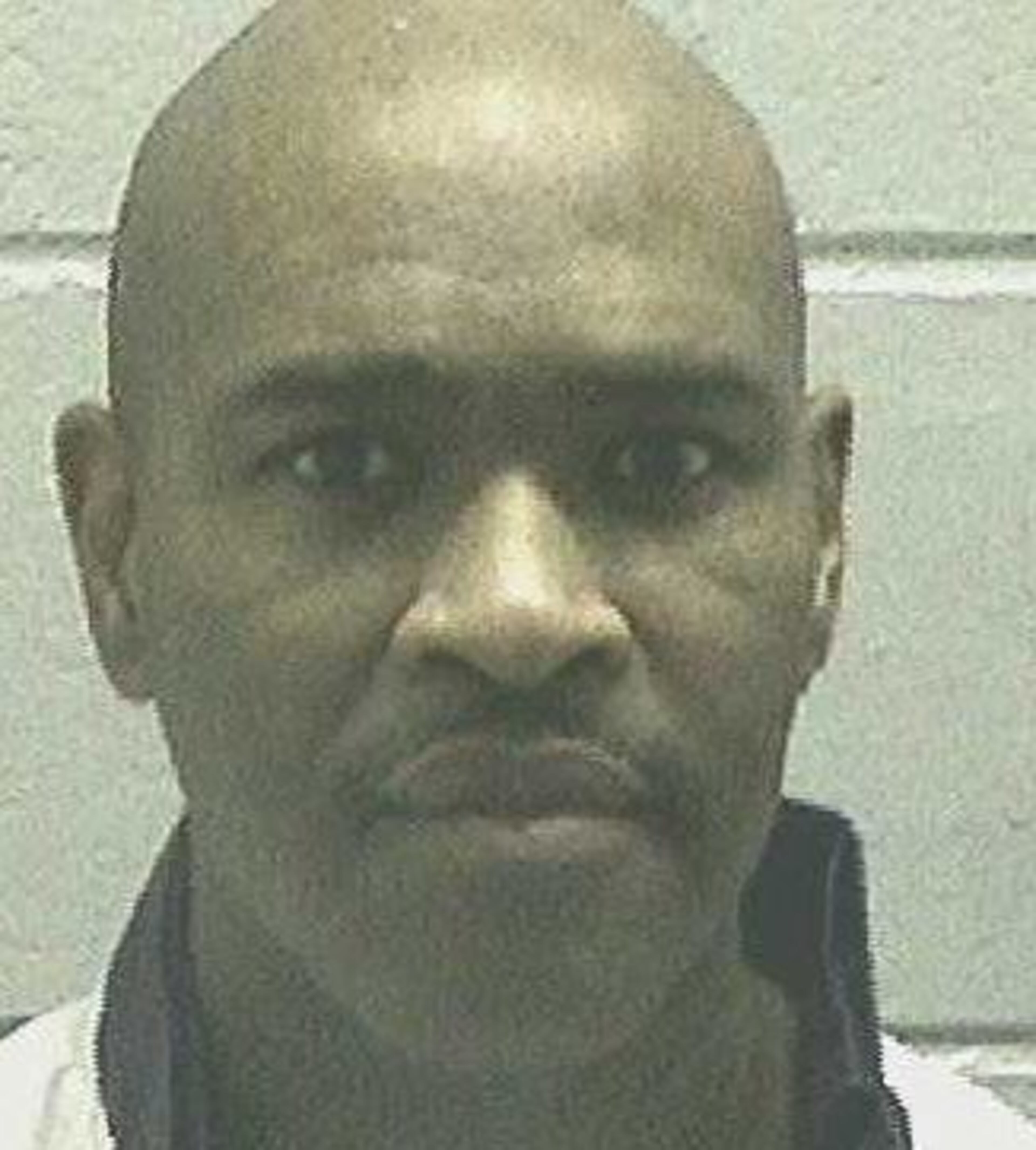

Brian Keith Terrell was put to death by lethal injection Wednesday at 12:52 a.m. after a nurse struggled for an hour to get IVs inserted into his arms. The execution came just hours after a sharply divided federal appeals court in Atlanta declined to stop his execution.

A three-judge panel of the 11th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals

unanimously rejected Terrell's request for a stay of execution, but two of the three judges expressed frustration with Georgia's lethal-injection secrecy law. In denying Terrell's appeal, they said they had no choice but to join the majority opinion because of a precedent the court set in September when rejecting a challenge to the law.

One of the judges said a condemned inmate should not have to wait for "a botched execution, or other mishap," before being able to access information about the lethal-injection process.

Terrell was sentenced to death for the 1992 murder of John Watson. Seven weeks after being paroled from prison. Terrell shot and beat to death the 70-year-old Watson to prevent him from reporting to police that Terrell had forged Watson's signature on stolen checks. Shortly before being put to death, Terrell raised his head and said, "Didn't do it."

In Terrell's final appeals, his lawyers argued that Georgia's law that classifies the state’s execution protocols as a state secret violated his due process rights, because it made it all but impossible to prove the procedure violates the Eighth Amendment's guarantee against cruel and unusual punishment.

On Tuesday, the 11th Circuit produced a 17-page opinion. It began with a brief explanation of why the stay was denied and was followed by three separate, concurring opinions by each of the three judges on panel.

Judge Stanley Marcus wrote that court precedent said there is no "broad right to know where, how and by whom the lethal-injection drugs will be manufactured, as well as the qualifications of the person or persons who will manufacture the drugs, and who will place the catheters." Marcus said he was bound by that precedent in rejecting the challenge.

Judges Beverly Martin and Adalberto Jordan, who also joined the unanimous opinion, both wrote that they believed the 11th Circuit wrongly decided prior challenges to the secrecy law.

"Of course, I recognize the state’s need to obtain a reliable source for its lethal injection drugs," Martin wrote. "But there must be a way for Georgia to do this job without depriving Mr. Terrell and other condemned prisoners of any ability to subject the state’s method of execution to meaningful adversarial testing before they are put to death."

A condemned inmate "cannot have received due process when he must wait for a botched execution, or other mishap, in order to get sufficient information" to mount an effective Eighth Amendment challenge, she said.

In its court filings, Georgia offered assurance that the drugs used to execute Terrell would work fine, but "Georgia's pleadings do not constitute evidence," Martin wrote. "Indeed, we have no reliable evidence by which to independently evaluate the safety and efficacy of the state of Georgia’s secret drugs. For me, this raises serious due process concerns."

Surely, Martin added, "if we can protect grand jury proceedings and commercial trade secrets, we can come up with a process that protects the important interests of both Georgia and Mr. Terrell" as the state carries out a death sentence.

Jordan, in his concurrence, was brief and to the point. He said he continued to believe the 11th Circuit wrongly decided a challenge to Georgia's secrecy law in September.

That challenge was raised by lawyers for Gissendaner, who was executed Sept. 30. Hours before the execution, Jordan dissented to the court's decision that denied Gissendaner a stay of execution.

"Georgia can certainly choose, as a matter of state law, to keep much of

its execution protocol secret, but it cannot hide behind that veil of secrecy once something has gone demonstrably wrong with the compounded pentobarbital it has procured,” Jordan wrote at the time.

“It is not asking too much to require Georgia to put on some evidence that will provide some level of confidence that its compounded pentobarbital is no longer a problem."

On Tuesday, Jordan said that because the court's decision in the Gissendaner case was binding precedent, he had to agree that Terrell's request for a stay should be denied.