A Fulton County grand jury has served subpoenas on a Cobb County judge to get sealed records for an ongoing criminal investigation involving the sex-tape case involving Waffle House chairman Joe Rogers Jr.

The subpoenas served March 18 on Superior Court Judge Robert Leonard seek audio and

Credit: Bill Rankin

Credit: Bill Rankin

video recordings, physical evidence and all records of a closed court hearing during which Leonard questioned Mye Brindle, Rogers’ former housekeeper. Leonard, represented by the state Attorney General’s Office, asked a Fulton County judge to quash the subpoenas. So did the Cobb County clerk of court, who was also served subpoenas for records.

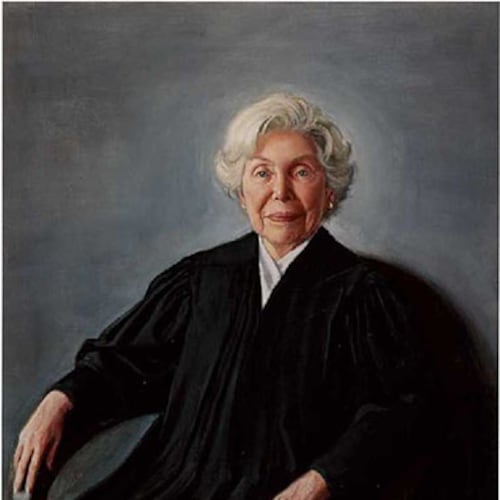

On Friday, Fulton County Superior Court Judge Shawn LaGrua found that the subpoenas had not been properly served and quashed them.

LaGrua noted that Leonard was not the custodian of the documents so he could not produce them. And because the records require a judge's order to have them unsealed, the clerk couldn't produce them either without such an order.

LaGrua said the Fulton District Attorney's Office could file a motion to unseal the records and that it's Leonard's prerogative to determine what should or should not be made available.

The confrontation stems from highly contentious litigation involving a secret video recording Brindle took while she performed a sex act on Rogers in his bedroom in 2012, according to court records. She made the recording a few weeks after retaining Marietta lawyers David Cohen and John Butters.

After the video was taken, Cohen sent a letter to Rogers on July 16, 2012, encouraging him to reach a large monetary settlement to resolve sexual harassment allegations. A failure to do so could result in media attention, criminal charges, divorce and the destruction of families, the letter said.

Rogers has denied harassing Brindle and said any sexual activity was consensual. Rogers’ lawyer, Robert Ingram, has said the Fulton grand jury is investigating Brindle and her two attorneys.

In Georgia, it is a felony to videotape the activities of another person in a private place without the consent of all parties involved. The subpoenas were served by an investigator who works for the Fulton District Attorney’s public integrity unit. The secret videotaping of Rogers occurred at his home in north Fulton.

The Fulton grand jury subpoenas seek evidence placed under seal by Senior Cobb Superior Court Judge Grant Brantley in November 2012. These include towels, letters from Brindle to Rogers and video recordings. Brantley said he was placing the recordings under seal because they included images of nudity and sexual activity.

Separately, the grand jury is seeking all records of a closed-door hearing in which Leonard ordered Brindle to appear and answer questions under oath about the circumstances surrounding the video she secretly recorded.

In their court filing, state attorneys had argued that Leonard was not the custodian of the documents, that he is granted immunity from having to comply with the subpoena and that the DA’s office has not filed a motion to unseal the documents.

In response, Fulton prosecutor Sheila Gallow said precedents set by prior court rulings say orders that seal evidence in a civil case and which have the potential to impede an “important criminal investigation” must give way to a grand jury subpoena. “This is the type of evidence required by the district attorney in this case by way of subpoena,” Gallow wrote.

But LaGrua, in a four-page order, said the DA's office failed to follow proper procedure.

In a prior statement, John Floyd, one of Cohen's lawyers, said Brindle's lawyers did nothing wrong.

"Ms. Brindle's counsel deny engaging in any illegal conduct," he said. "... The facts and the law will confirm that the video recording is legal."

Cohen, in a statement on Friday, said that in 2014 the State Bar of Georgia dismissed an ethics complaint filed against him by Rogers and his wife, Fran.

He also noted that a federal court judge in Atlanta previously ruled that the consent of only one participant -- not both -- is necessary for a video recording under Georgia law. The federal appeals court in Atlanta upheld that decision in 2001, Cohen said.

About the Author

The Latest

Featured