The group that’s supposed to ensure Fulton County’s rape victims get fair treatment from the legal system is back at work after years of failing to meet.

Georgia law requires the Fulton County Sexual Assault Protocol Committee to meet every year or face possible contempt of court charges. But the group for the county's nearly 1 million residents has not done so for two or three years. Fulton County Superior Court Chief Judge Gail Tusan re-convened it earlier this month after becoming aware that she's required by state law.

"A combination of unintentional factors caused the committee to just kind of lapse," Tusan said. She started as chief judge in 2014.

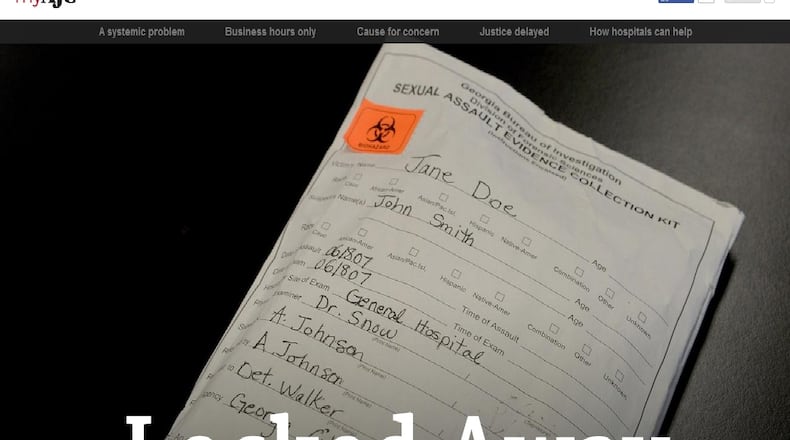

The committee's re-boot comes at a critical time. Earlier this year, an Atlanta Journal-Constitution investigation revealed that Grady Memorial Hospital, the county's sole rape crisis center, had been locking away some 1,500 packages of sexual assault evidence in file cabinets for 15 years, even when victims asked the hospital to give these rape kits over to police. We later revealed that Grady had been billing victims for evidence collection, which is against state law. Doing so is the ethical equivalent of sending a robbery victim the bill for dusting for finger prints.

Another problem at Grady: its 24/7 rape crisis center isn’t staffed 24/7. Also, a Grady representative told the AJC that trained personnel collect the evidence from victims, but would not describe what training they receive. Evidence collection is a specialized skill that requires training and certification.

The committee could decide to address Grady’s problems, Tusan said, but its main goal is to write a county-wide protocol for sexual assault cases. There is none, which also runs counter to state law.

Whether the committee will work on Grady’s problems remains to be seen. During the Oct. 7 meeting, it elected a Fulton District Attorney prosecutor as chair and a lawyer from Grady Memorial Hospital as vice-chair.

You may recall it was Grady Memorial’s legal team that argued – incorrectly – that the hospital could not give over rape kits to law enforcement because of medical privacy regulations. We refuted this claim. Federal regulations specifically allow for this, while state regulations require hospital cooperation with law enforcement.

(At times, the hospital’s rape crisis staff did try to give the evidence over to law enforcement, but the efforts went nowhere. In the early 2000s, hospital rape crisis staff complained that Atlanta police failed to pick up kits, and an investigation showed that police were destroying evidence and improperly handling sex crime cases.)

Tusan was upbeat about current efforts at inter-agency cooperation.

“The important takeaway is everyone responded,” Tusan said. “No one resisted coming.”

About the Author

The Latest

Featured